Oil Spill: New Painting in Ontario

Beneath the rumblings of the city, Saw Gallery’s exhibition “Oil Spill” reveals the refreshing vision of curator Stefan St-Laurent, who has presented over 40 works by new and established Ontario artists. The show’s title hints at the dark, provocative nature of many of the pieces, which are fi gurative paintings, with several leaning to the interdisciplinary. One of the most surprising aspects of the exhibition is its design. The single video work by Jeremy Bailey, Video Paint 1.0, was shown only at the exhibition’s opening, and was then on display on the artist’s Web site. The challenge of displaying the remaining six artists in such an intimate, artist-run space was met through innovative curatorial techniques. In devising methods to allot equal expression and balance to each artist’s project, St-Laurent subverted the traditional modernist white cube.

“Oil Spill,” installation view, 2007. All images courtesy Saw Gallery, Ottawa.

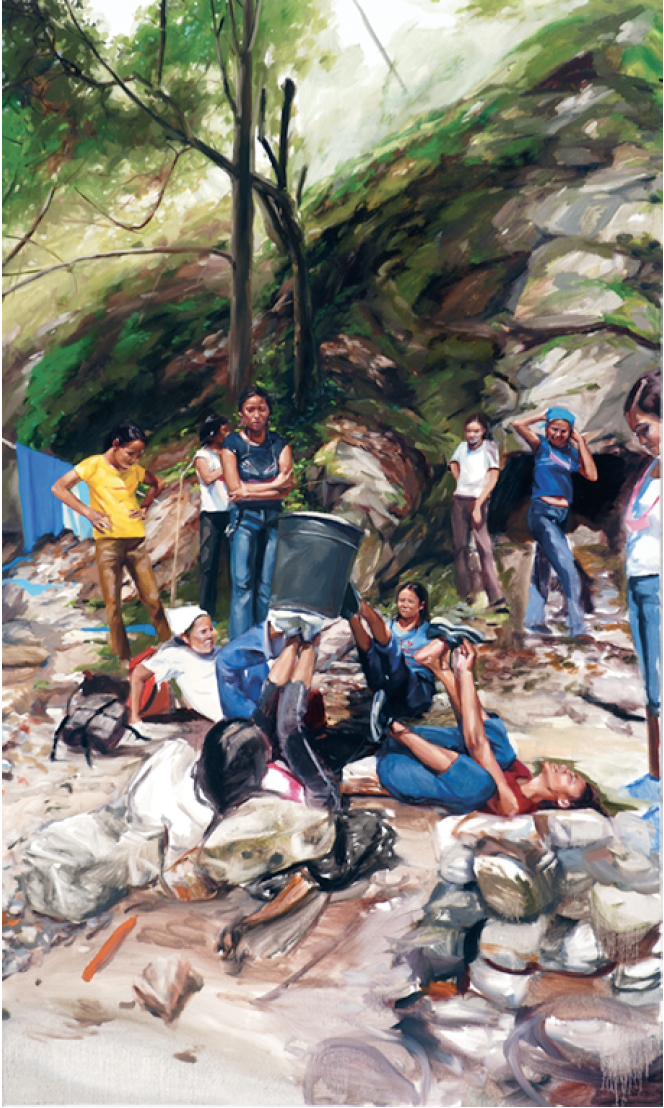

Each of the carefully chosen artists supports St-Laurent’s thesis: narrative painting is more satisfying than narrative cinema in its ability to provoke thoughtful, active responses from the viewer. This is especially true of the works of Jaclyn Conley, which were set in a small and starkly black room. In the silence of this void, her rhythmic and expressive use of colour, often verging on the abstract, spoke loudly. Conley is a storyteller, or, rather, a stager of stories that unfold with distinct characters—youth occupied within dubious, unsupervised scenes. At first, they seem idyllic or commonplace; in Wateredge three children have stopped momentarily at the edge of a body of water. While two seem unaware, one youth stares uncannily at the viewer, as if being captured on film. It is in a work such as Night where Conley’s themes are especially challenging. Boys congregate in a forest; the puzzling scene is caught in the strange glare from an unknown light source, perhaps the headlights of a vehicle. Why are they wearing goggle-like apparatuses? And why are two children dragging a figure into the forest? The unanswered questions leave viewers to worry over the children, who seem at once vulnerable and dangerous. Powerless, we observe them as they navigate the chaos of childhood experiences in the absence of adult control.

Kent Monkman, Sacred Vows, 2002, oil on canvas.

In the main exhibition space, an intimate atmosphere is created through a sumptuous rhythm of black, magenta and white walls interspersed with patterned wallpaper that mirrors motifs in the works. The Cree artist Kent Monkman has covered a wall of colonial-style silver on black toile with six detailed works, the injection of pattern serving to corroborate the tone of the paintings’ elaborate frames. His recurring theme—a post-colonial reversal of power relations that posits the homosexual domination of the white man by a Native oppressor—is presented in overt and graphic detail. On the opposite wall, the paintings of Michael Harrington are displayed on pink and black damask. They are careful constructions of open narratives, where he depicts atmospheric scenes with a dream-like blurring of images in dramatic stage-like settings. His colours are dark and expressive. Unfortunately, here the bright pink of the background is a distracting and jarring contrast. In the experimental design of the exhibition, this is the only perceived slip.

Kim Dorland, Three-Headed Deer, 2003–07, mixed media.

Two white walls break up visual space in the main room, effectively featuring Kim Dorland and Dave Cooper. Disarmingly grotesque, Cooper’s painted surfaces of pearlescent feathered strokes depict underwater worlds evocative of subconscious sexual drives. Kim Dorland’s eerily artificial simulacrum of a Three-Headed Deer is a vibrant sculptural extension of his textured surreal paintings. The figure of the deer is loaded with heavy paint in piles of vibrant colour, dripping strands that at once obscure and reveal its anatomy.

The work of Petra Halkes concludes the exhibition. In the obscured surface the viewer can discern a series of overlapping reflections through a glass window. At once juxtaposing the warm hues of the interior reflection with the exterior view, Halkes blurs the boundaries between them, subverting the seeming security of the enclosed domestic space and creating a series of complex perspectival relationships. Petra Halkes’s Delivered, a life-sized painting on paper, of a truck, is draped from the ceiling and unfurls onto the floor, one exposed wheel upturned on its flat surface. Navigating around this work to follow the exhibition, new angles and exposures of the twisted form can be seen.

Jaclyn Conley, Bucketlifters, 2006, oil on canvas, 36 x 60”.

Drawing from these sculptural cues, St-Laurent presents several paintings in relief through the use of mounting brackets, separating the canvases from the wall. The curator has succeeded in allowing each artist’s distinct style equal expression and weight. Were all the walls uniformly neutral, it would have been difficult to distinguish the artists’ projects. This system of balancing through design is enhanced by the sculptural elements of several works that enter into interdisciplinary modes.

In “Oil Spill” the accessibility of figurative painting is augmented by the immersive and dynamic exhibition design. Alluding to the familiar interior design of domestic spaces, St-Laurent has avoided what might be seen as the intimidating aestheticism of a gallery, expanding the audience of the art world beyond its current parameters. ■

“Oil Spill: New Painting in Ontario,” curated by Stefan St-Laurent, was exhibited at Saw Gallery in Ottawa from July 19 to September 15, 2007.

Valerie Doucette is a writer living in Ottawa.