“Oh Canada”

Everyone wants to like this show, “Oh Canada”; it’s our ‘E for Effort’ Canadian approach to most things. Canada, as I came to understand it in elementary school, is a cultural mosaic, whereas our neighbour to the south is a melting pot. With this perhaps now outmoded model in mind, how are we to view a curator from the US filling a museum with Canadian art and artists? Are we represented as our diverse mosaic, or has she turned us into contemporary art fondue, and does it matter?

MASS MoCA is a sprawling series of industrial buildings occupying 13 acres of the small New England town of North Adams. Its history is varied and includes a textile plant (1860–1942) and an electric company (1942–1985) before the museum’s development in 1986. Now, with its 100,000 square feet of exhibition space, its nearly 15-year renovation and a stellar reputation, it has provided an exhibition opportunity that sounds almost too good to be true. Attending the opening celebrations this past spring, I can assure you it’s not so simple a response to say, one way or another, whether that promise was fulfilled.

Prior to the opening, much information and conversation had circulated throughout our national art world. The curator, Denise Markonish, had, over a four year period, presumably done more than any Canadian curator in terms of studio visits (400) and geography covered (everywhere but Nunavut). For the exhibition, Markonish set out to take the pulse of art currently being produced in Canada. She was steadfastly not interested in reiterating our own relatively small pantheon (those artists we count as our own who have managed to surpass the national identity and go on to worldwide recognition). To add to the microscopically close attention Markonish has paid, the exhibition is also on view for a full year. This is essentially unlike any art show that has focussed on Canada in the past and, rightly so, is being billed as the largest exhibition of contemporary Canadian art to ever take place in the United States. That being said, it isn’t necessarily all roses.

BGL, Canada de Fantaisie, 2012, outdoor installation, MASS MoCA, North Adams, Mass., dimensions variable. Courtesy the artists, Parisian Laundry, Montreal and Diaz Contemporary, Toronto. Images courtesy the Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art, North Adams.

Logistically, we can consider the work in three categories: recent work, new work, and commissions. With more than 100 works presented by 60 artists occupying 14,000 square feet of exhibition space, I want to make special note of the commissions, which are all really good, namely Divya Mehra’s neon sign, Hollow Victory (You gotta learn to hold ya own. They get jealous when They see ya with ya mobile phone.), 2012; A Coin in the Corner, 2012, by Micah Lexier; and Legacy Maple, 2012, by Craig Leonard et al. It’s worth mentioning that if you weren’t looking for these three works, you might miss them. Mehra’s neon light that reads “WE MADE IT IN AMERICA” is literally outside the gallery proper, installed above the entrance leading from the lobby. A white ray of lights mimicking a snowy rainbow (or maybe the Great White North) sits atop the word “AMERICA,” which is in purple and flickering as if already broken. A student of colour theory, Mehra is quick to point out the associations of the colour purple with royalty and power. By incorporating the Tupac Shakur lyric in the title, she conflates the dissemination of information from message to medium; after all, it is a neon sign—supposedly celebratory, but ultimately another emblem of failed capitalism in a malnourished community. This is a question more than a statement—calling out the notion of success in terms of who is paying attention and from where they do so. Lexier’s piece is, unmistakably and endearingly ML. The artist had 100 coins specially minted, with the title on one side and a diagram of their installation on the other. The coins were then affixed to the floor in 100 corners of the institution (not just throughout the galleries dedicated to “Oh, Canada” but also the museum’s administrative offices, washrooms, even in the adjacent Sol LeWitt drawing retrospective—something I’m sure would have tickled that artist to no end). To say nothing of the implications of Canadian currency occupying this massive American institution and the minimalist gesture of placing a single piece of silver on a concrete floor (grey on grey), coupled with the double entendre of coin also being the French word for corner, all adding up to another smart and fully realized work by one of our country’s leading conceptual strategists. Craig Leonard’s readymade, an eight- by four-foot slab of MDF board tucked away beside the freight elevator, could easily be missed or mistaken as part of the architecture if it weren’t for the gallery label attributing the work to no fewer than nine people. As an artist interested in labour, artistic and otherwise, naming all those involved in the work’s creation (sourcing, shipping and installation) is appropriate. This very clean, confounding work exemplifies, or maybe synthesizes, the North/South relationship succinctly—an individual is offered an opportunity and attempts to take advantage of it in the most polite way possible without making too much of a fuss, even aesthetically.

Divya Mehra, Hollow Victory (You gotta learn to hold ya Own. They get jealous when They see ya with ya mobile phone.), 2012, neon sculpture, 36 x 72 x 9”. Photograph: Timothy Harrison.

Surprisingly, the curatorial installation of already existing works was more effectively done than the new commissions. For example, Wanda Koop’s Look Up, 2009—a deliberate template of 49 medium-sized bevelled-edge canvases mounted some 30 feet high, climbing a pale blue painted backdrop—could, in this instance, trick the eye into thinking it was watching a slowed-down film reel, the artist’s monochromatic washes of acrylic rhythmically balanced and effortlessly hovering in the space. Similarly, Garry Neill Kennedy’s Spotted, 2009/2012, a playfully slanted grid of 72 large-scale digital prints of CIA-rendition airplanes (planes that are used for transporting suspected terrorists such as the Canadian citizen Maher Arar in 2003), was presented on a blue painted background (this time royal blue). Kennedy’s found photo-documentation of government activity is positioned looming above the doorway into the enormous space, weighing heavily on the shoulders of those who noticed, and simultaneously out of sight and out of mind for those who didn’t—an instance where artistic concern is echoed in practical placement in this exhibition. Kim Morgan’s 57-foot latex cast of a lighthouse-like structure, Range Light, Borden-Carleton, PEI, 2010, brings the artist’s East Coast iconography to the fore, even in its wilted capacity. These three installations were able to take advantage of the ample verticality offered in the Museum’s hangar-like industrial retrofit, two-story space.

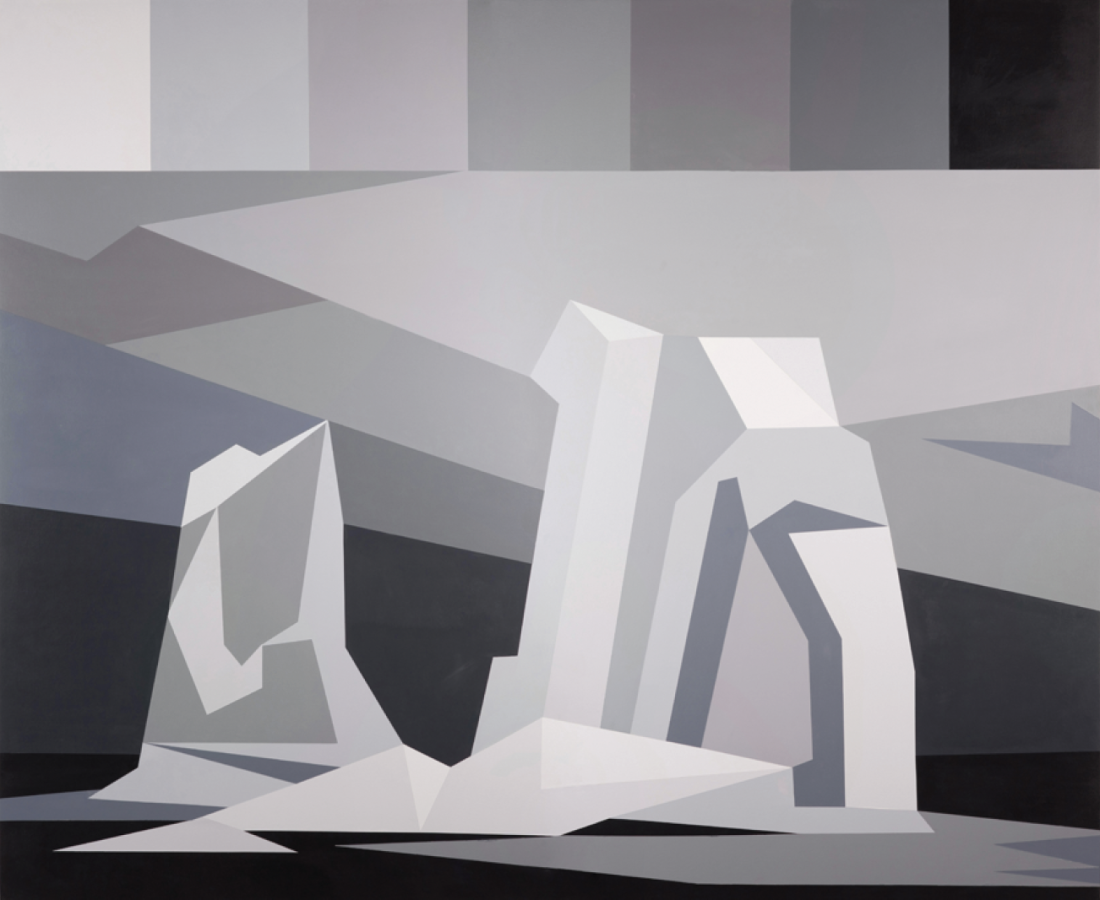

Then there is the new work, not commissioned but also having not made the rounds of Canadian galleries. These pieces function almost without context (the lone wolf syndrome). The works of Brendan Fernandes, Nicolas Baier, Marcel Dzama and Hans Wendt (among others) derive from some alternate reality or geographic other—neither Canadian nor American—suggesting we’re eavesdropping on a conversation that is almost over, having missed the important introduction. That’s not to say this work isn’t strong or that it won’t last—more to the point, it exhibits a sophistication and precision that is almost absent in most of the other work present. The work is not cutesy; there are no gimmicks, no overt references to Canada. These pieces make the others seem a bit clumsy, perhaps, more of what I imagine Americans think about Canadian art—which, of course, is untrue, and is exemplified by work of someone like Douglas Coupland taking up the paintbrush in a typically cool tip of the hat to Lawren Harris’s monumental landscapes. In Coupland’s machination the cool blues and theosophical angles become computer-generated shades of grey and pixilated micro grids. There are other examples of our well-educated brethren sampling from their histories, such as Wally Dion’s Game Over, 2011, comprised of computer motherboards and the faintest thread of neon inspired by traditional Aboriginal blanket patterns, advancing the conversation in a successful way.

Sarah Anne Johnson, Cheerleading Pyramid, 2011, unique chromogenic print hand painted with acrylic ink, 27.5 x 41.5”. © the artist.

Given such an expansive look at production, and with so many kinds of art and artists presented, it’s worth wondering whether the exhibition is privileging a particular kind of art. There is an inclusive presentation of installation, drawing, painting, photography, video, sculpture and even performance, but does one form appear more often than others? Certainly we can discuss the handmade quality in much of the work: Graeme Patterson’s multi-layered exploration of the artistic process; David R Harper’s utopian-driven triad; Luanne Martineau’s elegant, if not uncanny, felt sculpture; Chris Millar’s exploded installation of minutiae or the elegant hybridity in Clint Neufeld’s sculptures.

Due to the exhibition’s broad range we see brief moments in which echoes, or instances of smaller exhibits or pairings among the larger whole, appear almost magically, or it may well have been a curatorial strategy. These complete sentences amidst the paragraphs include eloquent pairing of Michael Snow’s 62-minute video, Solar Breath (Northern Caryatids), 2002, with Charles Stankievech’s dizzyingly, powerfully intimate installation, LOVELAND, 2011. In this unwitting duet we have, at one end of the spectrum, Snow, with likely the most accolades a living artist can receive (in his own country and abroad) next to the young Stankievech, who was just short-listed for the Sobey Art Award last year. Perhaps these two under the same roof could register as one of the great Canadian moments in international presentation. Another very powerful grouping is the dream-like ellipsis on the second floor of the museum that includes installations by Noam Gonick and Luis Jacob, Daniel Barrow, and Hadley+Maxwell, predicated by the drawings of Shuvinai Ashoona. Noam Gonick and Luis Jacob’s Wildflowers of Manitoba, 2008, now in its 11th iteration, having been previously presented in Canada, the US, Germany and Belgium, is the first of the three isolated, back-to-back installations a viewer sees on the second level. This multimedia work that includes five data projectors, an audio track of French Canadian prog-rock and a live actor playing the role of teenage daydreamer, all taking place under a geodesic dome, might be understood as the quintessential pastiche of feeling and location that exudes an isolation and ultimate possibility for the marginalized wanderer.

Douglas Coupland, Arctic Landscape Fuelled by Memory, 2012, acrylic on canvas, 78 x 96”.

In a world-class space such as MASS MoCA, it’s the tiny missteps that can add up to less than an entirely comfortable reading: too often the audio elements of video works are eclipsed by one another or drowned out by their placement; not enough attention was paid to the location of three-dimensional works, made more evident by a preponderance of two-dimensional pieces; finally, for a gallery with such ample space, crowding work together seems an odd choice when we see that there were at least three other exhibits on at the time whose space might have been allocated in part to “Oh, Canada.”

In the end, does this exhibition succeed? Where it may fall short of total success is in its failure to draw any clear conclusions about contemporary Canadian art. But it does succeed as a de-facto survey as much as any biennial or other art world attempt at large-scale categorization. “Oh Canada,” with the impressive 450-page MIT Press publication accompanying it, will benefit from time. Indeed, Markonish concludes her curatorial essay with the notion that “this is just a snapshot, one curator’s view, one moment that will hopefully become a part of the vast history…a snapshot that will spark a dialogue continuing well after the exhibition is packed in boxes.” I agree. In 10 or 20 years from now anyone interested in contemporary Canadian art will be obliged to have “Oh, Canada” in their aesthetic photo albums. ❚

“Oh, Canada” is exhibiting at Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art, North Adams, from May 26, 2012 to April 1, 2013.

JJ Kegan McFadden is the Director/Curator of PLATFORM Centre for Photographic + Digital Arts in Winnipeg.