Objects of Wonder

In art, as in life, pairing is the most delicate and intimate of relations. Curator Sigrid Dahle has been exploring the twosome, first with Bill Eakin and Sarah Crawley, and now with Aganetha Dyck and Karen Thornton, in a series she calls “Affinities.”

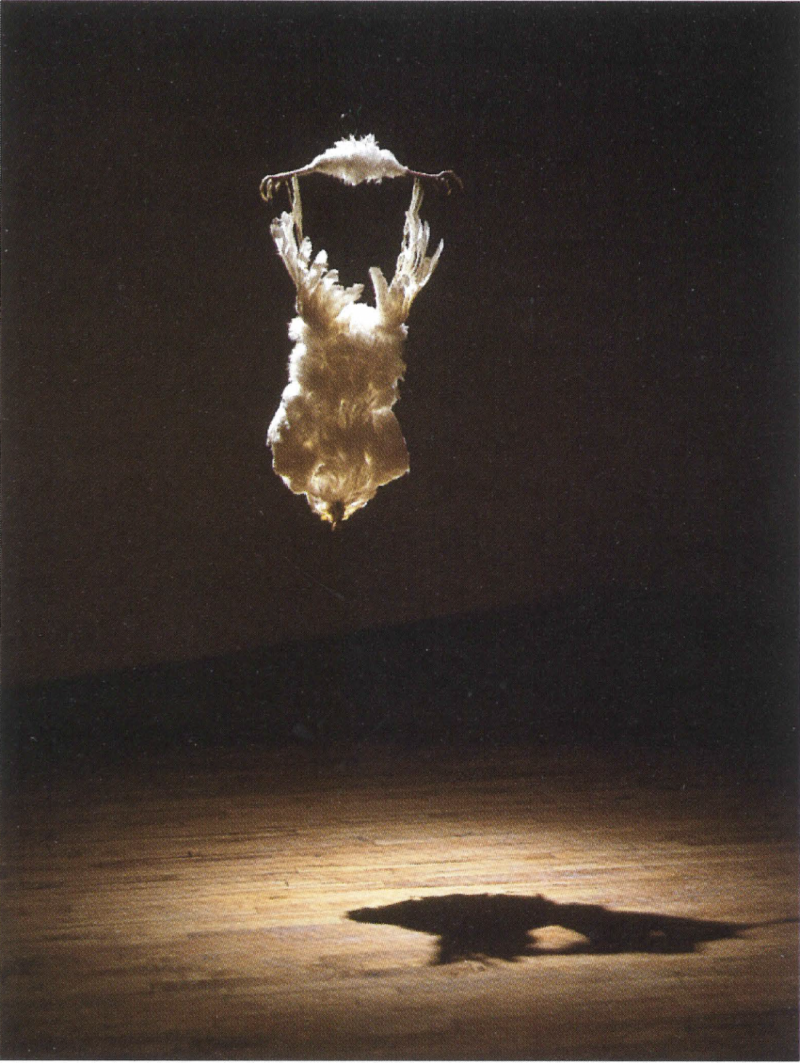

Karen Thornton, Layer No. 9, 1994, poultry. Photographs: Sheila Spence.

A two-person show brings about a certain dynamic. It’s not like the solo, with its self-contained, sometimes self-satisfied clarity. And it’s not a group show, with often disparate artists hovering around some theme or region or period. Instead, the two-person show illustrates a Saussurian law of linguistics—things are not defined absolutely in themselves, but are defined in relation to other things.

To hook up the works of an established artist with those of an emerging one, Dahle looks for a certain hard-to-define resonance. In this case, the work of the senior artist, Aganetha Dyck (who currently has a retrospective at the WAG which will subsequently go on a national tour) and the work of recent School of Art graduate Karen Thornton share certain obvious characteristics—the beautiful but visceral use of animal products, for example. Dyck uses bees and hives; Thornton favours what she often tersely labels “poultry.”

But more important than the appearance of the finished product is a certain way of working, one that is based in those natural and not entirely controllable materials. In response to the Romantic myth of artistic creation, in which a god-like artist bends brute matter to his will (I’m using non-inclusive language quite deliberately here), Dyck and Thornton both allow for accidents, for serendipity and for materials that have minds of their own (sometimes literally). Thornton, for example, requisitioned a dead chicken in 1994 to use in her “Layers Series.” In fact the poor dear wasn’t dead, and Spunky, as she came to be known, was adopted and was soon providing eggs for later pieces. Dyck’s art often changes in situ, with hot lights hitting wax or bees buzzing around, transforming the work. Dyck may carefully set things up, but at some point she lets them go. It’s this willingness to work with the unforeseeable consequences of the physical—of the body, of life and death and change—that brings together the art of Dyck and Thornton.

Karen Thornton, Shell No. 6, 1995, eggshell and hen’s feet.

Dyck’s work intrigues me because it combines the geometric regularity of the honeycomb with a wonderful, fragrant, dripping messiness. Thornton takes chicken eggs—perfect, smooth, complete—and threatens or smashes them. Within these simple tensions of control and release, perfection and corruption, both artists manage to evoke extraordinarily complex issues of female identity. Without specifically representing women, without any easy narratives, they wrestle with issues of sexuality, reproduction and role-playing.

Thornton’s use of chickens is inspired. Their reproductive processes are at once constrained and unnaturally extended; think of the battery hen, jammed into a cage, turning out egg after barren egg. They are not just female, but seen as “feminine”; think of their anthropomorphized versions in cartoons—gossiping, dowdy matrons. Dyck’s use of bees also brings into play all sorts of associations—the evocative image of the queen bee, grotesque in her subjugation to reproduction; and of course, the sexual connotations of honey.

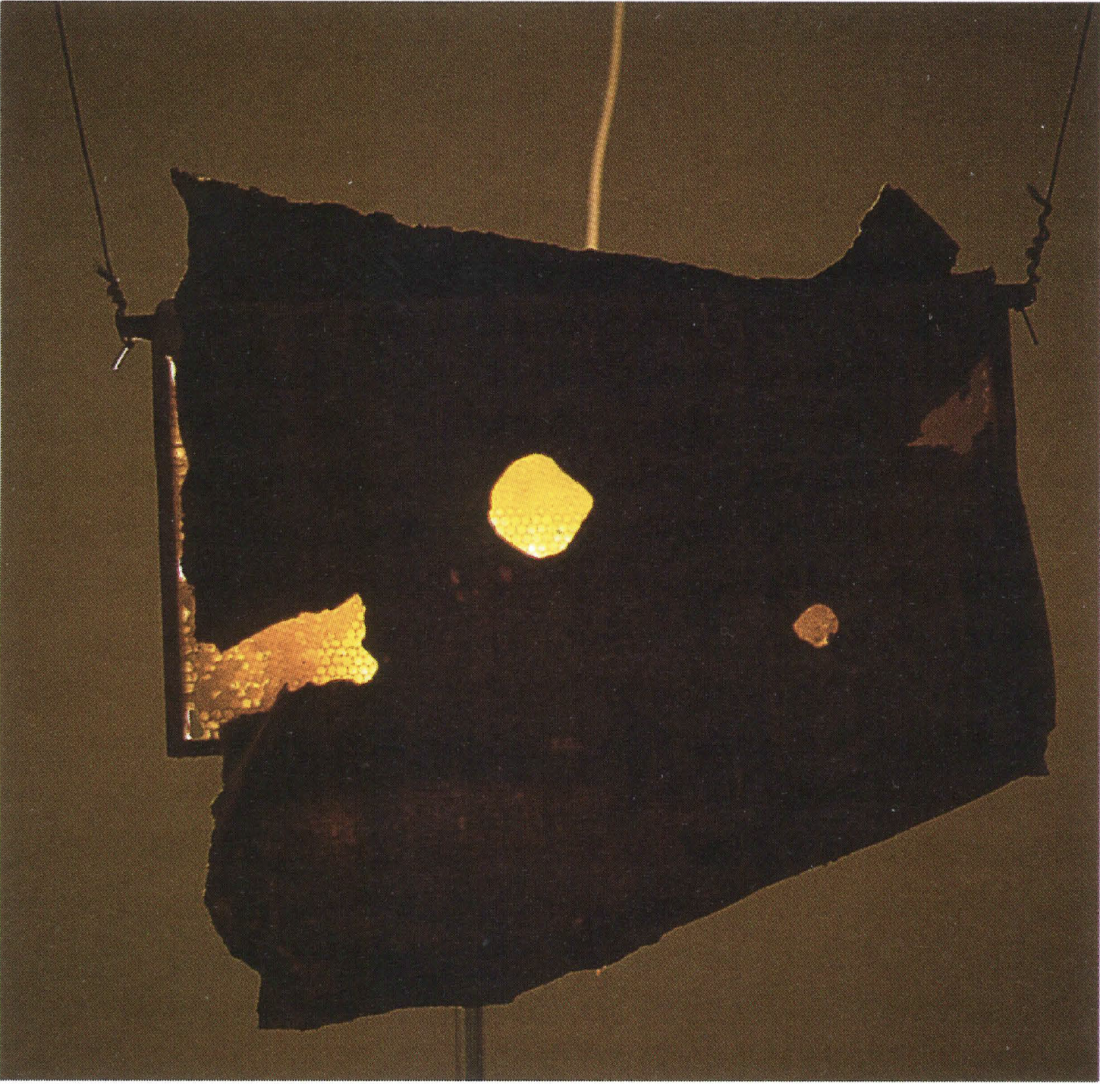

Aganetha Dyck, Night Watch, 1995 mixed media.

I have talked more about process than the finished products in the show, perhaps responding to the artists’ underlying affinity for a certain kind of practice. But the objects are wondrous. Thornton offers an eggshell made even more frail with a myriad of pin-pricks. Her shoe of eggshells and down is funny, lovely, mythical, impossible. Layer no.9 seems like a fluffy little piece of lingerie, chicken feathers forming hour-glass curves. Only when you walk around it do you see the flayed hides that are the foundation of this ideal. And Dyck’s Nightwatch is roughly beautiful, formed of honeycomb and rusted hive blankets and light and heat and smells.

“Still life,” as the show is called, is of course, anything but still, using animal-based processes and products to evoke the continuing transformations of the body. ♦

“Still life” Aganetha Dyck and Karen Thornton, Ace Art, March 24 to April 15, 1995.

Alison Gillmor writes frequently about the visual arts for Border Crossings.