Objective Portraiture

Luther Konadu, the Winnipeg-based photographer and writer, is on a roll. In 2019 he won three national competitions: BMO’s 1st Art!, the Scotiabank New Generation Photography Award and the Salt Spring National Art Prize. He has done residencies at Salt Spring Island and at Gallery 44 in Toronto, where he was writer-inresidence, and was commissioned by the New Yorker magazine to do a portrait of Roberto Carlos Lange, the electronic folk pop singer who performs under the name Helado Negro. Konadu is also the content provider for Public Parking, an online magazine for emerging artists (now in its fourth year); he is Akimblog’s Winnipeg correspondent; and he has had solo exhibitions at the National Gallery of Canada’s PhotoLab6 in Ottawa; the Museum of Contemporary Art in Toronto; PAVED Arts in Saskatoon; the White Water Art Gallery in North Bay, Ontario; Latitude 53 in Edmonton; and the New Gallery in Calgary.

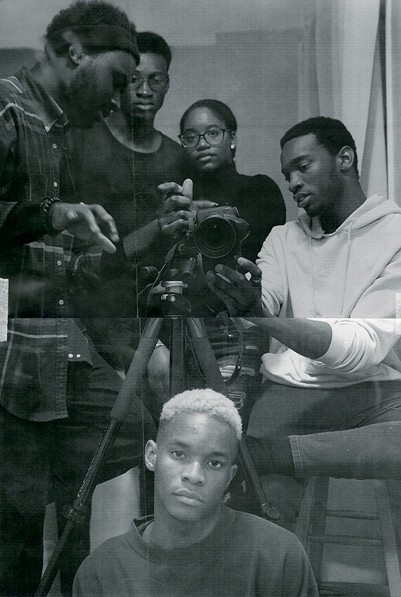

Luther Konadu, from the exhibition “Figure as Index,” 2018, Latitude 53, Edmonton. Images courtesy the artist.

In 2019 he also received his BFA from the University of Manitoba, where he managed to avoid taking any classes in photography: “As a student you could get access to cameras and so I took them out to see what I could do with them. It was a struggle because I didn’t know what I was doing, but it was also liberating because I could do whatever I wanted.” He started with self-portraits and eventually began to photograph his friends and people he knew in the city. He photographs only young Black men and women, but their skin colour is not what interests him: “It could be anyone in my images. Anything to do with Blackness is secondary to my making a portrait.” Konadu has been consistent in recognizing that the photograph is a construction and not a window into representation. “I think of the figures in my images as being anonymous and their identities as de-specified,” he says. He has looked to the early photographs of Thomas Ruff, which he describes as “huge passport-like portraits which don’t tell you anything about the people,” and at the documentary photography of LaToya Ruby Frazier. He admires the subtlety of the way she mixes “silent moments with performative gestures that teeter between fact and fiction.” He recognizes that “just looking at a camera is a performative act and it immediately engages you in the action of making that image,” but his aim is to capture the silent moment more than the star turn. None of the people in the images are named, and he sets a series of restrictions on what they can wear and how they appear: no clothes with recognizable logos or too many graphics, no jewellery or anything that is busy and, because he wants “something undefined in their facial expressions,” there is no frowning or smiling. What is evident is their presence. As a viewer you feel like an intruder in a space where you don’t belong and you are equally aware that the space belongs to the people you are looking at. What complicates this relationship is their way of looking out; it is somewhere between indifference and dismissal. “I definitely want to give them the agency of looking back at whoever is looking in,” says Konadu. “There is a lot of power in looking back and that power is owning yourself and owning the space that you’re in.”

From the exhibition “Figure as Index,” 2018, Latitude 53, Edmonton. Images courtesy the artist.

Konadu doesn’t so much take photographs as he makes re-photographs, and his subject is not the figure but the medium itself. His insistence on the medium explains the content of many of the images. Because he photographs in his studio, the mechanics and the paraphernalia of photography are everywhere; lighting stands, electrical cords and tripods creep into the edges of the images, as do clusters of previous images attached to the studio walls behind the portrait subjects. Konadu sees his work as one continuous, ongoing project. “If I go back and edit a photo, or take a photo from my archives, it’s just picking up where I left off,” he says. “It’s never a question of thinking of a new idea.” He turns to music to explain how individual photographs operate within the overall frame of his production: “I feel that a single track out of an album can stand on its own and do what it does, but then within the context of the album, it does something different.” The photograph, then, reveals its artifice and additionally displays the strategies of how it is made. You see evidence of multiple frames and texts, folds and image overlaps and snippets of coloured tape on the seamless surface. Konadu uses the diptych form to emphasize that the photograph is more about making than taking. He has images in which the left-hand side of the photograph will be saturated in a single colour, while the other half presents groups of self-composed young Black men and women doing nothing other than being who they are in the space in which they situate themselves. In one photograph from “Figure as Index,” the left-hand side of the image shows a pair of re-photographs with highlights of red tape on a rich blue ground. On the right half a beautiful young man sitting on a table turns away from his friends and towards the viewer. He stares out confidently as we peek in. His gaze puts us in our place. ❚

Order Issue 152 here. _