“NYC 1993: Experimental Jet Set, Trash and No Star”

When an institution frames an exhibition as a “time capsule” or a “vertical cross-section” of the artistic production of a particular place and time, you can’t help but ask the inevitable question, “So, what does it say about that place, that time?” And the obligatory follow-up: “How then does it speak to our contemporary condition?” This particular form of retrospective—the spatio-temporal retrospective—requires the viewer to answer those questions by piecing together from the selected cultural fragments something resembling their own vague remembrance of that location, however distant/invented that might be. Within this conjuring a picture is formed, and when successful, one that is recognizable as having been lived in by our imagined ancestors.

Gabriel Orozco, Isla en la Isla (Island within an Island), 1993, silver dye bleach print, 40.6 x 50.8 cm. Courtesy the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery, New York.

For those not present in New York in 1993, New Museum’s “NYC 1993: Experimental Jet Set, Trash and No Star” succeeds in transporting through a swirling vortex the concerns and preoccupations that would define that locale. For those who were present, I expect that the revisitation of these works, once again in New York, would produce something verging on nostalgia. Though, given the mood of uncertainty, anxiety and fear present throughout the exhibition, I can’t imagine these being particularly warm and fuzzy memories. And this is perhaps where those on their first trip to the New York of 1993 meet those on their second go around. The urgency motivating these works remains so present it is unsettling.

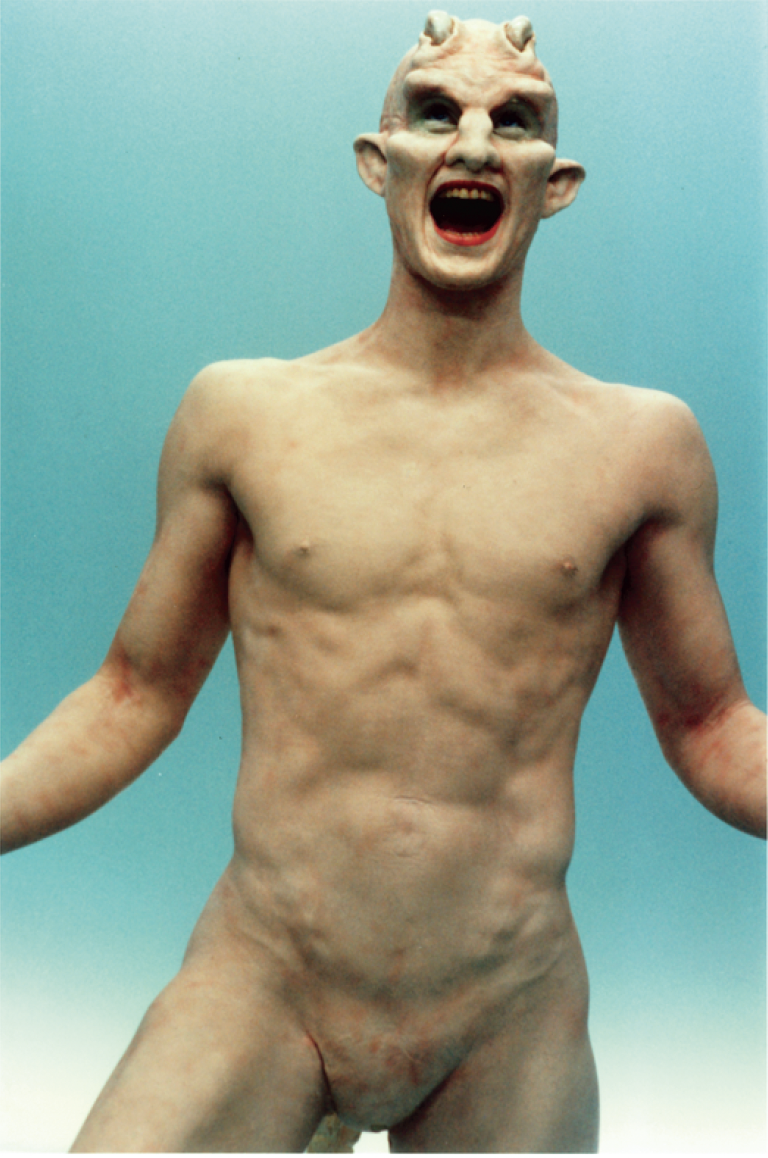

Matthew Barney, DRAWING RESTRAINT 7, 1993, video still. Video: Peter Strietmann. Courtesy Gladstone Gallery, New York/Brussels. © Matthew Barney.

The most remarkable in the evocation of this sense is the exhibition’s fourth floor. After stepping out of the elevator and onto Rudolf Stingel’s bright-orange carpet conceptual painting, you are immediately entranced by the ominous melody of Kristin Oppenheim’s lugubrious voice in “Sail on Sailor” as she intones the now melancholic chorus of the eponymous Beach Boys’s song. As beautiful as both of the above works are individually, in the context of this installation it is as if their presence is meant in the service of Felix Gonzalez-Torres’s Untitled (Couple), which hangs from high above, emerging from the recesses of the fourth-floor ceiling to provide only just enough light to peer into the darkened corners of the room. Illuminated by its spill are Gonzalez-Torres’s “Untitled, 1992–93, Billboards” in grey-scale, upon which a lone bird navigates a brooding, overcast sky. The remarkably sparse and simple installation on this floor allows the contemplative space necessary to be fully absorbed by these works either individually or when considered as an autonomous, immersive work in its own right.

To do an installation of this haunting intensity on every floor would perhaps seem heavy-handed—although I couldn’t have faulted them for attempting it—and throughout the second and third floors the exhibition reverts to more standard retrospective display tactics. Within this format, though, there is still room to be moved, as descending the stairs from the fourth to the third floor the viewer is confronted by two works explicitly addressing the AIDS crisis that was overwhelmingly present in the lives of artists working in 1993. Installed adjacent to one another, both Gregg Bordowitz’s video Fast Trip, Long Drop and Nan Goldin’s photographs of her friends Gilles Dusein and Gotscho devastatingly exhibit the urgent concerns and anxiety compelling the production of work in this place and time where the stakes are the health and safety of those closest to you.

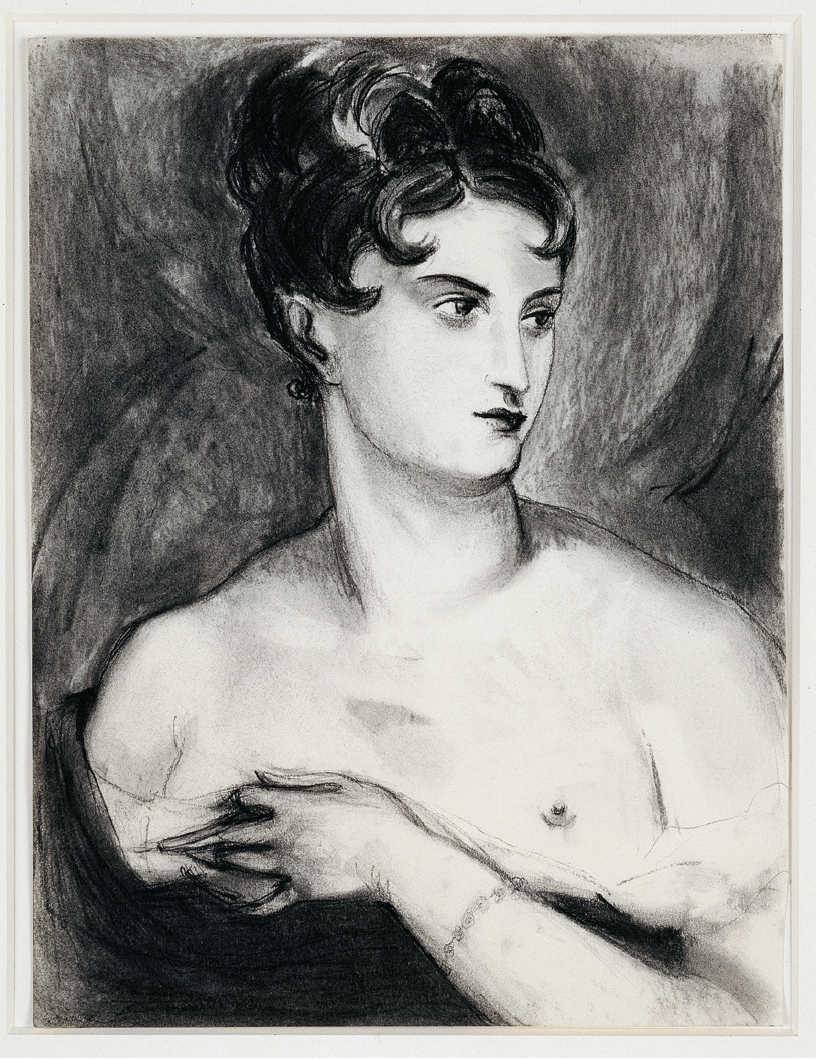

Elizabeth Peyton, Mademoiselle George, 1993, charcoal on paper, 59.7 x 52.1 cm. Courtesy Gavin Brown’s enterprise, New York. © Elizabeth Peyton.

On my way out through the lobby of the New Museum I overheard a couple discussing 1993 as the year that the ’80s “officially” ended. It is a year that, until the occasion of “NYC 1993,” I hadn’t paid much thought to. However, it is borne out through the exhibition that 1993 was a pivotal moment culturally, economically and socially. The AIDS crisis, unrest in Europe, an ongoing war in the Middle East and debates on healthcare, gun control and gay rights in the United States were all very present in the lives of those living, working and showing there. The sense of urgency in all of the work is clearly evident, but also quite specific. As such, many of the works feel dated—and generally, it’s a date too near to wear the patina of time flatteringly. Others—Mike Kelley’s “Garbage Drawings,” Alex Bag’s Untitled (Spring 94), Art Club 2000’s Gap ads for Art Forum—would continue to look prescient alongside the work in any international contemporary institution. Whether or not a few, some or all of these works have lost the sweet shine of their immediate location is of course interesting, but is ultimately irrelevant. What “NYC 1993” develops instead is a time capsule that divulges what it meant to be human in that place and time, a detail often obscured when slotted into a more opaque program. In its breadth, it speaks to the human condition responsible for making art, one which is outside of institutionalized concerns and one that must continue to drive production at this present moment, and into the future. ❚

“NYC 1993: Experimental Jet Set, Trash and No Star” was exhibited at New Museum, New York, from February 13 to May 26, 2013.

Aryen Hoekstra is an artist currently based in Toronto.