“null = 0. dutch avante-garde in an international context, 1961-1965”

In 1961, a small group of Dutch artists, Armando, Henk Peeters, Jan Henderikse, Jan Schoonhoven and herman de vries, formed the Nul (ZERO)-group, which aimed to replace personal expression in art with objective representation of reality. Wanting to break art out of its special, hallowed place and bring it down to real life, the group found they had much in common with artists in other countries: the German ZERO group, the French Nouveau Réalisme, the Italian Azimut and the Japanese Gutai movement. Although their motives were often different, the artists in these groups created installations and assemblages from industrial and natural materials and phenomena such as water, wind and light. They de-emphasized the artist’s skills and foregrounded the viewer’s perception in the experience of an artwork.

Assemblage and collaborative art strategies are indispensable to many conceptual art practices today, and “nul = 0,” an extensive exhibition on the Dutch Nul-group and their international contacts, provides a welcome historical link. Organized by the municipal museum in Schiedam (near Rotterdam) this fall, the exhibition is accompanied by a comprehensive publication (in Dutch and English). The richly illustrated book contains interviews with artists of the Dutch Nul-group, still-active octogenarians and essays by curators Colin Huizing and Tijs Visser, among others.

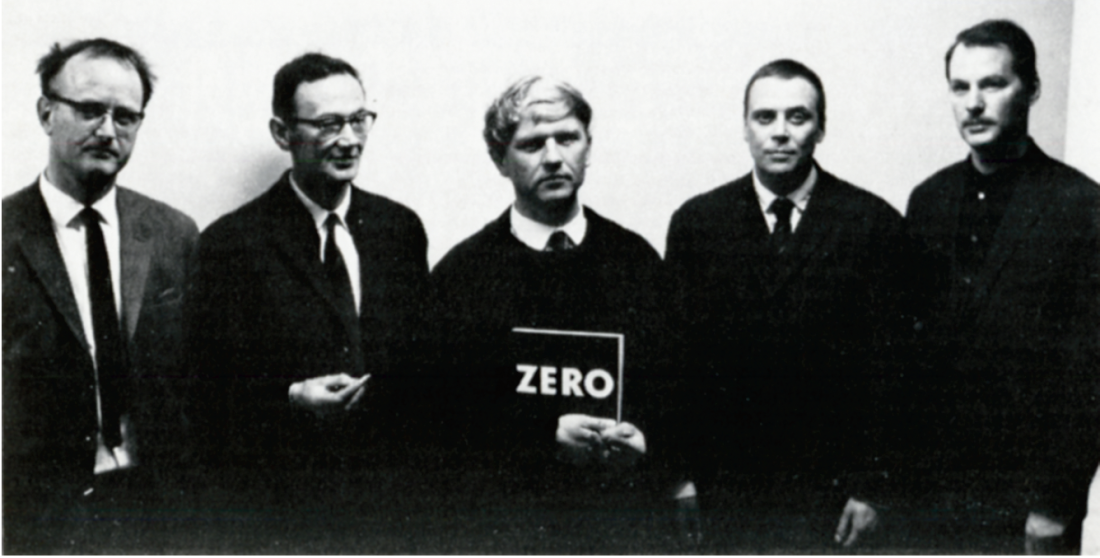

Nul-ZERO: Henk Peeters, Jan Schoonhoven, Heinz Mack, Gunther Uecker en Armando, from exhibition “Zero-0-nul,” Gemeentemuseum, The Hague, 1964. Courtesy the Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam.

Rich in anecdotes, the book provides a glimpse of a pre-Internet era when international contacts among artists depended on chance meetings, art magazines and snail mail; artists’ desires to cross borders pre-date the computer age. Wanting to break with “dangerous nationalism,” Nul-artist Peeters, in particular, went out of his way to get in touch with like-minded artists such as Yves Klein, Yayoi Kusama and Lucio Fontana, as well as the ZERO, Nouveau Réalisme, Azimut and the Gutai groups. Between 1961 and 1966, these international artists, similarly interested in breaking the established order and reaching a new point of departure for art, collaborated in provocative exhibitions organized by Nul in Amsterdam, The Hague, Düsseldorf, Paris and Milan.

Kusama was contacted from New York by Peeters, who wrote to her dealer after he had seen an advertisement for her art in the magazine Cimaise. She first participated in the 1962 Nul-exhibition at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam and continued to exhibit in the Netherlands for years after that. In a number of performances, she managed to get young men to strip and then painted their bodies with her signature dots. A photo of that time shows even the usually staid Jan Schoonhoven, who had a regular job at the post office, in the buff.

The Nul-group often broke with institutional procedures and spaces and organized and networked on their own initiative. In 1962 an exhibition slot of 16 days had opened up at the Stedelijk in Amsterdam and Peeters asked director Willem Sandberg for use of the space. The show was completely organized and paid for by the artists themselves. Many international artists took part in this key exhibition, titled “Nul 62.” While using different materials and methods, they shared a desire to present the “real” without subjective contamination. Pierro Manzoni signed the arms of girls and declared them authentic works of art, Bernard Aubertin set fire to his assemblages of matchsticks, and Christian Megert constructed an interactive mirror installation. In an upbeat period of technical and economical progress, “everything was beautiful,” as Nul-artist Armando later recollected.

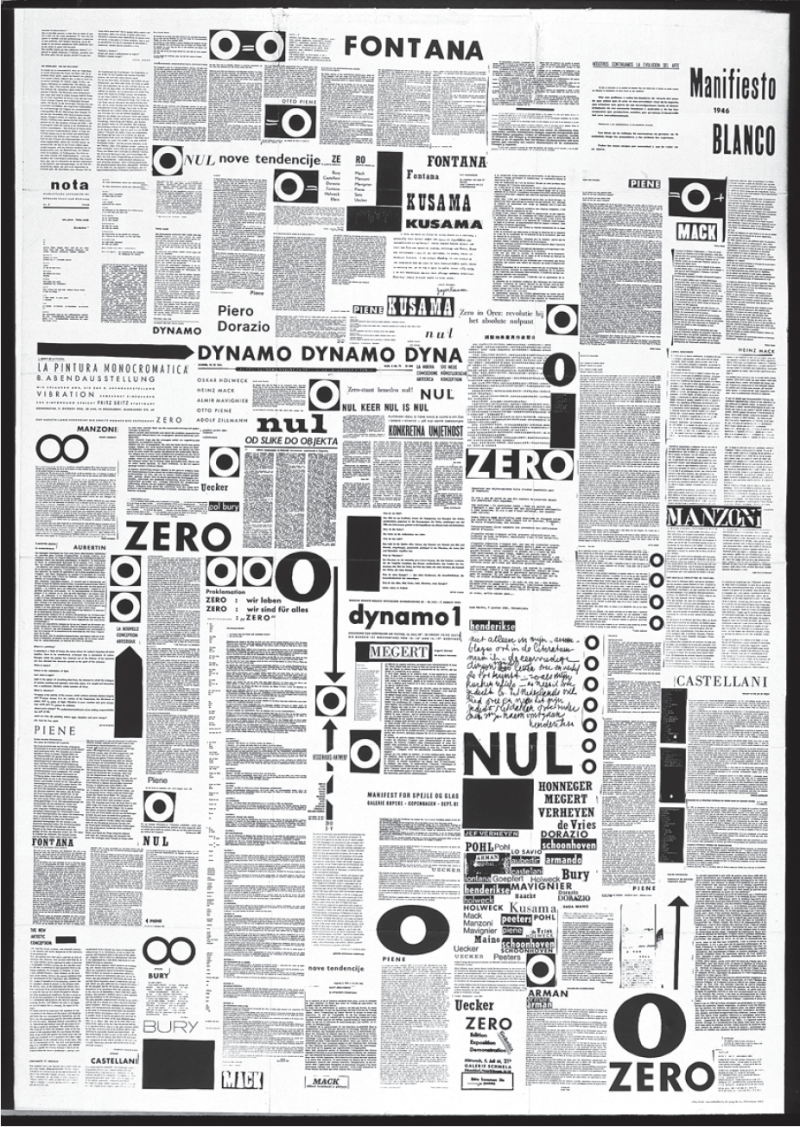

Catalogue for the exhibition “NUL 62,” Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam.

The present Schiedam exhibition, with over a hundred works, many re-created for the occasion, shows the international breadth of the movement and sheds light on the importance of the Dutch Nul-group within it. Henderikse built walls of empty, crated beer bottles and assembled matchboxes, cigarette boxes, plastic champagne corks and the like. De vries, who joined Nul for a short time, and Jan Schoonhoven were the more contemplative artists of the group. Influenced by Zen, de vries contributed white monochrome paintings and objects. Schoonhoven, who died in 1994, and whose work has recently garnered international attention, created many white geometrical reliefs with bits of cardboard and papier mâché that, in his words, “avoid any form of hierarchy, any centre.” The Schiedam exhibition also shows a re-creation of his Kartonreliëf, 1964, stacks of thousands of identical strips of cardboard.

Armando’s use of industrial materials tended to the dark and daunting. Among his contributions are shiny oil barrels, black barbed wire or black metal bolts on monochrome black paintings, and 36 brand new tires clustered on one wall. Today, tires in an art museum barely raise an eyebrow. A reviewer of the 1962 exhibition, however, sarcastically commented that “[Armando’s] contribution demonstrated an unbelievably deep insight in doing nothing. After inspecting the load of car tires, he let museum technicians install them, received 400 guilders for advertising the tires, and then stood in front of them, hands tucked in the pockets of his neat blue suit, happy with his creation.”

Breaking with the image of the romantic, bohemian artist was part of the group’s intention to bring art down to earth. Avoiding the “crafty” hand, Peeters once exhibited a large display fridge and hung some polar bear fur above it. Like the German ZERO artists Otto Piene and Günther Uecker, Peeters also used natural phenomena such as light, fire and wind to create interventions and installations that transformed spaces inside and outside traditional art institutions.

The ZERO movement’s use of modern industrial materials was a forerunner of today’s art of accumulation and installation. Their writing and proposals and, for example, Nul’s planned but cancelled exhibition on the pier in Scheveningen in 1966, which became the only artwork shown, can be seen as precursors of conceptual art. The Schiedam exhibition and book that show the ’60’s ludic, revolutionary reprise of the early avant-garde’s comparatively tentative forays into everyday life (Dada, Duchamp) form welcome additions to the discourse on the merging of art and life that continues to this day. ❚

“nul = 0. dutch avant-garde in an international context, 1961-1965” exhibits at the Stedelijk Museum in Schiedam, The Netherlands, from September 11, 2011, to January 22, 2012.

Petra Halkes is a painter, curator and visual arts writer living in Ottawa.