New Art from Manitoba

The Winnipeg Art Gallery, September-November, 1983

This show pretty well indicates current trends among young Manitoba artists. All are obviously talented and promising. Although there is a certain coherence, as Gary Essar, the curator of the show, states in his preface to the catalogue (“The artists are working in a vocabulary which I would generally describe as figurative”), the claim is somewhat wishful and forced. John Canaday, formerly art critic of the New York Times recently observed in a lecture here that painting is a “residuary art.” In other words, it is no longer culturally relevant. I have no doubt Mr. Canaday is correct, but this does not, for reasons too lengthy of elucidation here, detract from the significance of the place of art in society today. But his observation poses an immense problem for the artist, who must find his vision among the debris of historical attrition either by affirming the individual imagination or by assailing the falseness of assumed values. One pole is the extreme of surrealism, a persistent trend in the 20th century; the other is mockery and satire. Both polarities are to be found in the New Art from Manitoba Exhibition.

(Left to Right) Frieso Boning, James Doran, Allen Hessler, Tom Lovatt, Randal Newman, Gail Noonan, Diane Pura, Patrick Treacy, Slobodan Vujović, Marsha Whiddon. Photos Courtesy of The Winnipeg Art Gallery.

Tom Lovatt’s paintings impart an almost painful intensity. It is not often you find exactly delineated figures that relate pictorially within a context of fantasy. The method is derived from Surrealism but Lovatt has put his own stamp on the procedure. An almost hallucinatory relationship exists among a panorama of figures, the rationale for which exists only in the iconology of the artist’s imagination. The resulting tension is at once satisfying and disturbing. These fairly large oils are technically fine and they look well, both from afar and close up. The artist has obtained an intricacy of texture combined with strength of colour and image. The only danger here is the spectre (imminent, not quite yet present) of formulaic process: the point might become the mere incongruity of the subject, the seemingly random juxtaposition of the figures. Landscape 1983 is farthest perhaps from this tincture of the arbitrary; there is a logic in the contrast between the remotely spaced figures and the energy of the sky. The painting suggests a dream world which is convincingly tangential to everyday experience.

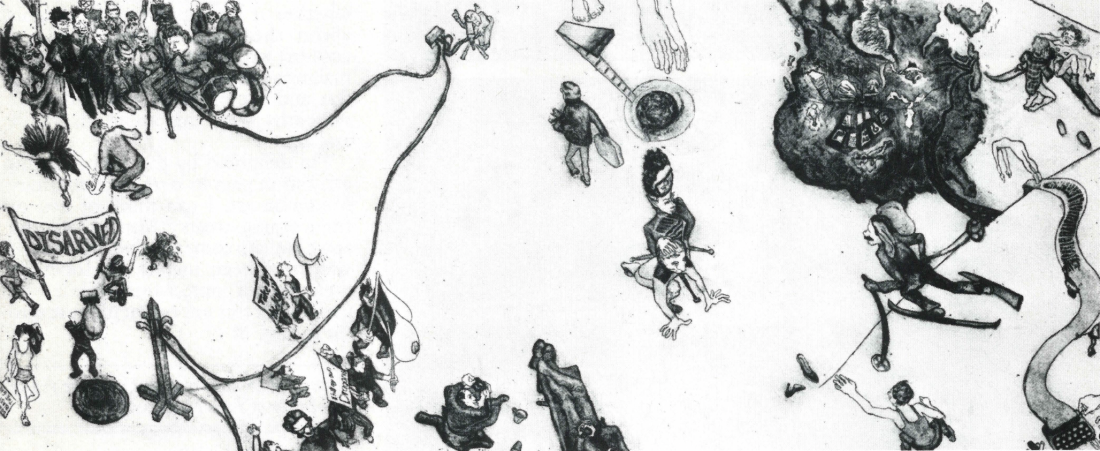

The etchings of Gail Noonan take the viewer into a world of fantasy. Unlike Lovatt this artist has no concern to establish an equivocal tie with reality. In the catalogue she states, “My images are the result of daydreaming or extended fantasizing on actual events in my life.” Her aims, then, are not lofty and her restraint and sense of structure provide this surrealist vision with an aesthetically pleasing stability so often lacking in this genre. She obtains the textural feeling that creates depth and the incision of line that gives crispness, a fusion which is the necessary property of a good intaglio print. The technique strictly serves her predominantly illustrative character and it is refreshing to find in a printmaker today this sobriety, this refusal to indulge in technical gimmickry and mere effect. I do not mean to imply any degree of tameness in these prints; they exploit a whimsy that traces some pretty precarious recesses of the psyche.

The images of Slobodan Vujović are stark and arresting, but their execution tends to be mechanistic and crude. The illustrative and didactic elements predominate. Veritas, for instance, depicting a female allegoric figure, is particularly heavy-handed. When this painter is less overtly concerned with delivering a message his painting derives power from its directness, as in Adam and Eve. Here the effect is subtly derived from a complex human sexuality. Vujović truthfully associates frustration with eroticism by means of both symbolism and graphic psychology. The texture of his painting reflects his involvement in human feelings. The work probes deeply into the human psyche and projects a deep insight with regard to the Biblical fall. Adam, forlorn, confused and diminutive in the background, witnesses the erotic contortions of Eve as she succumbs to the wiles of the serpent. The overall effect is significantly bizarre, a sine qua non of painting that strikes to the core of human experience. Another Kind of Tree is successful in another way. The idea and the image come inevitably together and convey the wonderful impression of spontaneous generation. Mr. Vujović is best when least preoccupied with intellectual intent.

MARCH FROM ONE END TO THE OTHER, Gail Noonan, 1983, Etching, 27.4 x 62.2

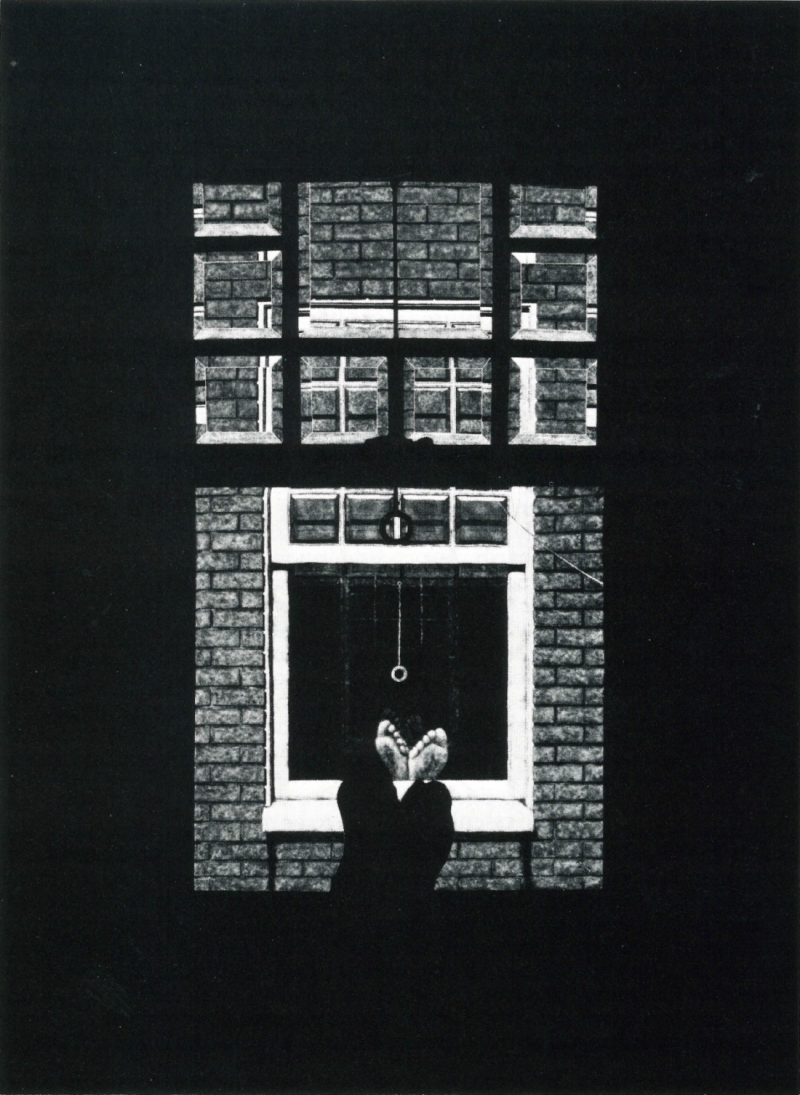

The enamels of James Doran establish an interesting change of pace to the show. They are elegant and inventive. The umbrella piece, Desert, is a little slight and perhaps even cute but the underlying craft imparts real distinction. His scope is varied. He ranges from whimsy (Desert) to the rigours of formalism (Disc, Right Round Square Sphere). The latter are impressively austere and somehow suggest an actual object, futuristic and strange. Voyeurs is a tour de force bringing together the artist’s playful fantasy and ingeniousness with formal structure.

Randall Newman’s paintings are, with one exception, abstractions on a theme. The exception is a large painting with figures in violent movement—a dance, as he indicates in the catalogue—related to the theatrical stage. This artist has lots of ability and seems to be striving for a style and a vision of his own. On the surface his work has the cast of avant-garde originality, and considerable competence in execution and design are evident. His images are not “abstract” in the old sense, for he intends to depict a specific visual structure related to the subject matter of the stage. But the underlying conception is of formal relationship and texture.

I am struck by the fact that these works which convey a distinct air of innovation, have a déjà vu aspect; Newman, like so many younger artists, is trying for impact rather than immersing himself in an individual vision stemming from inner conviction. The temperament, the expertise, are there; the inner conviction has yet to come.

VOYEURS, James Doran, 1983, Enamel on Copper, 78 x 58

Patrick Treacy’s drawings and paintings reflect an exactitude of representation that refuses to remain on the surface but subtly probes a depth behind the appearance, whether in portraiture, landscape, or still life. The coloured pencil medium is most congenial to his vision and with it he expresses nuances that are lacking in some of the oils, although not in the large landscape of Precambrian forest and rock. Here a total involvement in an aspect of nature, in which every detail contributes an eerie presence, fuses perfectly with the execution. The colour is harsh, but finely modulated, and the picture captures an ominous aspect of the Canadian wilderness, one that is entirely absent in the Group of Seven and its derivatives. The self-portraits are remarkable psychological probings, despite the apparent straightforwardness of technique and the attention to objective truth. Dream Figure is one of the best things in this show and evinces an angular, prickly Gothic quality that is an essential ingredient of Treacy’s vision.

Diane Pura’s approach, like Treacy’s, is scrupulous in detail and modulation. Sky Garden, for instance, incorporates precise observation with a volcanic motion that is reminiscent of Leonardo da Vinci. The delving into the unleashed energy within apparently static, organic forms poses the problem of structure, a problem well resolved in Wall Garden, where a bold horizontal holds everything together. The drawings are remarkable in their intangible (I’m tempted to say spiritual) delicacy. In the catalogue the artist speaks of deliberate ambiguity as a major concern and this aspect is uncannily and at times, horrifically, present. Miss Pura possesses an amazing technical ability well under the control of a fine sensibility.

Of Marsha Whiddon’s work, The Agressive Shadows impressed me as conveying an authentic and distinct sensibility. Man Dreaming has something of it too. One feels here the influence of two very disparate figures, Lautrec and Redon and later, Sheila Butler. There is something fascinating about this odd combination and its evident genuine assimilation. The larger oils do not quite have this authenticity for me. Arena Triumphant is bold, vigorous and well painted but a lack of consistency in the images, due, I think, to this artist’s attempts to resolve external influences, weakens the effect. The dog image in this and the other pieces is weak, too normal somehow despite the boldness of execution. The ferociousness of the animal is absent although this would seem to be the point of the image. You want something monstrous, not just an ordinary dog. There is a tentativeness beneath the undeniably strong execution. I wonder if the gouache and chalk works indicate where this artist is headed?

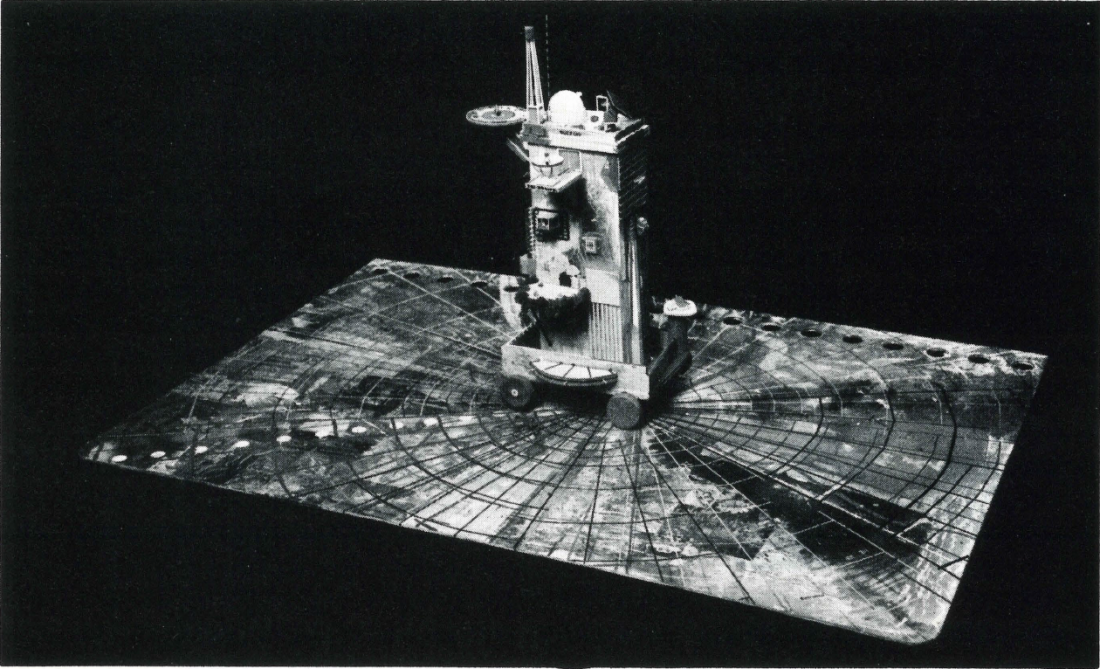

UNTITLED, Frieso Boning, 1983, Mixed media, 87.2 x 183 x 122

Alan Hessler’s paintings derive unashamedly from Expressionism, and this is in line with the current trend designated as Neo-Expressionism. I don’t see anything wrong with this at all. I believe that in the art world attempts at innovation have been moving too fast and have become in themselves boring gimmickry. I think an artist today must seriously consider following paths that still hold out possibilities and scope for real originality, rather than seeking the absolute new direction, which is usually superficial and almost immediately outmoded by the next experimentalist. Mr. Hessler’s large, colourful oils present images that have a personal or historical meaning, but not in an obvious allegoric or didactic way. He thinks in terms of image, and unlike many of the European Neo-Expressionists, his paintings have a vitality and authenticity that an overly theoretical execution cannot equal. He has a good sense of colour and structure: the iconography is strong, symbolic rather than explicit, and he has a knack for integrating images within a daringly fractured framework. In places, the brushwork is too flat and deliberate, but this flaw remains a minor distraction. This artist has also included a video installation which provides some very good moments, although like much of this art form, it lapses into self-infatuation and is too long. As a young lady was overheard to remark, “it’s not bad if you’re not interested in plot.”

On Frieso Boning’s constructions I find it difficult to comment. He has a message, although a cryptic one. In addition, the pieces are fun to look at, possibly, as the artist himself comments, “because they were fun to do.” Whether it’s merely a playful innovation or whether it can impart deep insights about the contemporary world, I couldn’t say. Certainly Mr. Boning is making a statement as well as just having fun and I confess to a considerable sympathy with this approach to life and art.

I’m delighted by the attention this exhibition pays to new, contemporary Manitoba art. I can think of two or three young artists (“Mini” Davis and Scott Barham come to mind) who might well have been included. Hopefully their day will come. Meanwhile let’s be grateful for this important glimpse into the future. ■

Arthur Adamson is a poet and the visual arts editor of Arts Manitoba.