Natascha Niederstrass

“Every work of art is an uncommitted crime.” Natascha Niederstrass takes that suggestive epigram from philosopher Theodor Adorno’s Minima Moralia, 1951, and runs with it in her latest solo exhibition. Certainly, she embraces the underlying assumption that art should be as free from shackles as thought itself. Shackles are enervating, after all, whereas Niederstrass’s unfettered art freely names perps and ferrets out secret histories in an attempt at reparation. She shakes us out of our complacency and guts misogyny where she finds it through the probing lens of a slyly transgressive and altogether sophisticated art.

Niederstrass here focuses on the murder of 22-year old aspiring actress Elizabeth Short, also known popularly as the “Black Dahlia,” who was found murdered in Los Angeles in 1947. In an exhibition earlier in 2015 at Gallery 101 in Ottawa, Niederstrass dilated on the hypothetical involvement of Marcel Duchamp in the murder. After the body—cut in half at the waist and drained of blood—was found in a vacant lot in Los Angeles, a massive police manhunt began. From the first, there was no shortage of suspects and scores of people confessed to the murder. Notably, Duchamp was not one of them. And the police were never able to marshal enough evidence to collar anyone. Still, as I noted in a recent monograph on the artist, not all admissions of guilt are made in church confessionals or in the interview rooms of police stations.

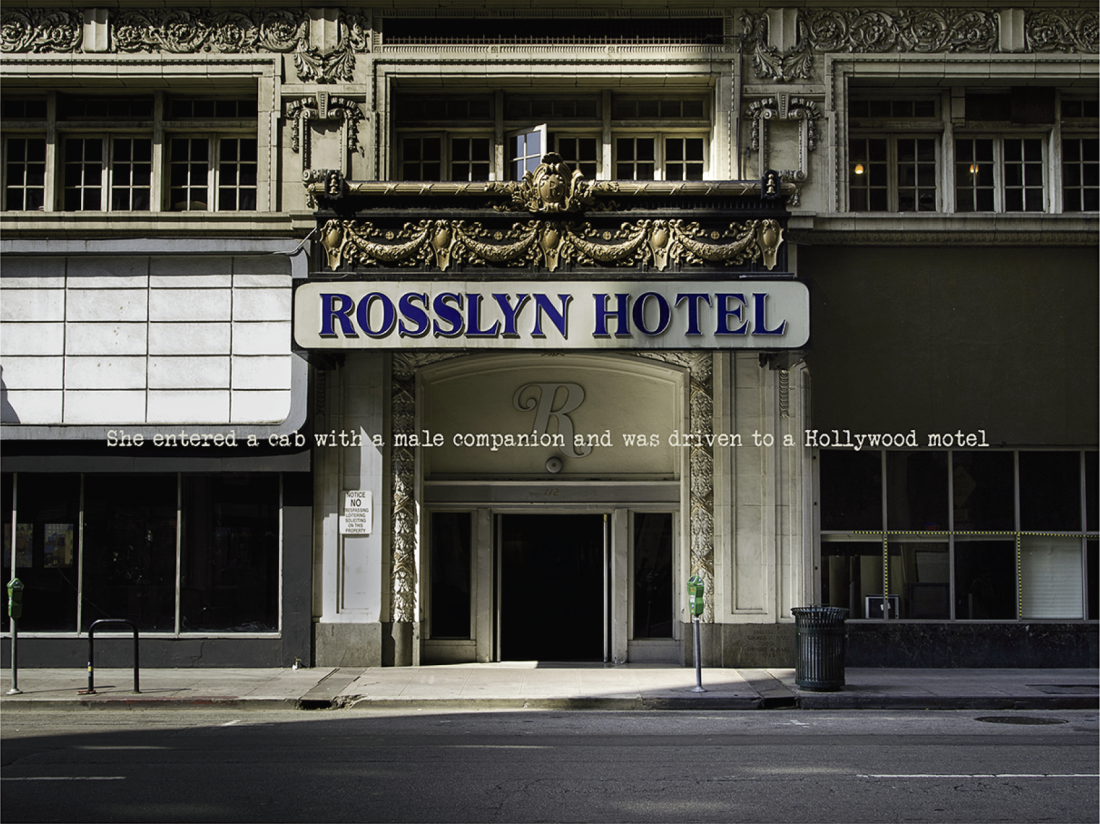

Natascha Niederstrass, Sunday, January 12th, 1947, 2015, inkjet print, 20.25 x 27.5 inches. Courtesy Galerie Trois Points, Montreal.

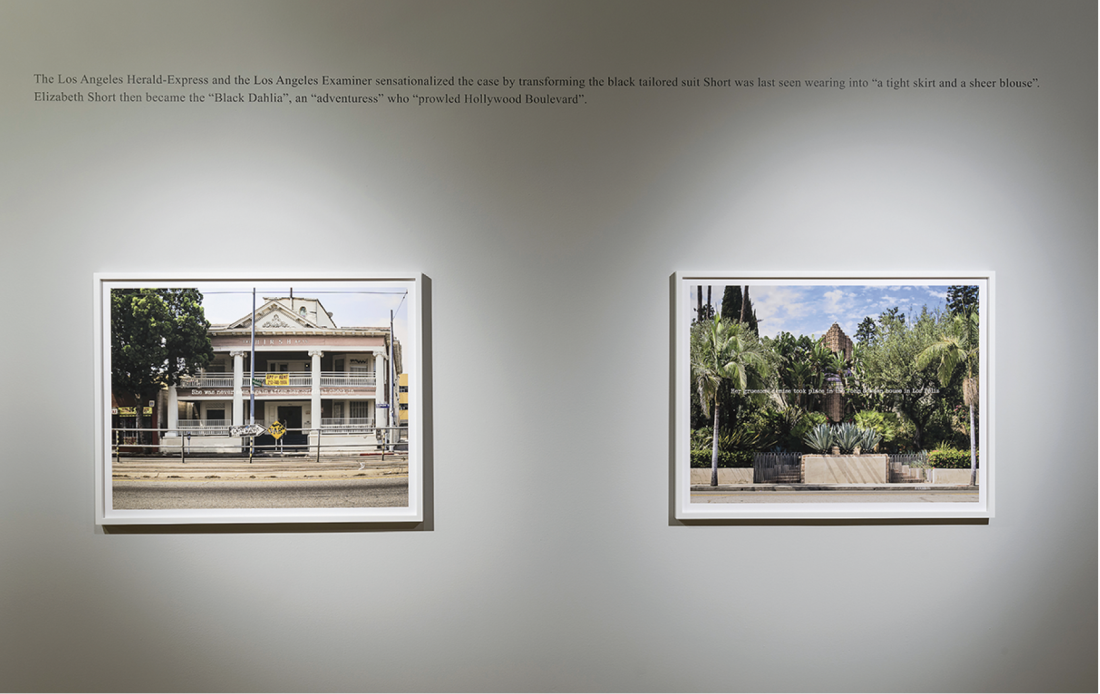

Now, using archival records of the LAPD (Los Angeles Police Department) and research published by Steve Hodel (a private detective, former police investigator and son of an alleged murderer of Short), Niederstrass expands her purview, narrows her focus—and deepens the mystery. She turns her close attention to the “missing week” before Short’s death. She has produced a documentary series of photographs of varying locations where sundry witnesses reported seeing Short in the seven days before her mutilated body was discovered. Many of these locations have not changed appreciably since the murder. In works like Thursday, January 9th, 1947, Friday, January 10th, 1947 and Saturday, January 11th, 1947, we follow in Short’s footsteps, as it were, in order to retrace her path, if not her trajectory towards what fate held in store.

In related works such as absentia luci, tenebrae vincunt, a sort of memorial portrait of the dead woman (a black dahlia on a funereal black ground), Witness Sightings and FBI Archive Records, and photocopies of the case files, Niederstrass neatly dovetails a ‘case file’ concerning the murder. She deftly questions the veracity of various newspaper accounts, effectively naming their reporters as co-conspirators in attempting to explain, in sensationalistic terms, why the murder was committed.

Natascha Niederstrass, Monday, January 13th, 1947 (left) and Tuesday, January 14th, 1947 (right), installation view, 2015, inkjet print, 20.25 x 27.5 inches each. Courtesy Galerie Trois Points, Montreal.

Over the last few years, Niederstrass has earned an enviable reputation for informing her work with forensic aesthetics and infusing it with a fulsome measure of chilling, even spine-tingling premises and implications. Like any good haunting, her installations inhabit the inside of our own heads with alacrity and are slow to exorcise. She uses great technical virtuosity in tandem with a remarkable gift for generating and sustaining mood and aura that catches her viewers unawares.

Niederstrass’s artistic practice has as its laudable and necessary theme a tenacious feminist exploration of violence against women based on sources that include crime scene photography, murder cases, horror cinema and even the literature of the spectral and unseen. She shares with her fellow traveller, photographic artist Emmanuelle Léonard, an abiding interest in forensic methodologies and her research touches on themes related to the Freudian concept of the uncanny. As we experience Niederstrass’s ambiguous narrative and its haunting mise en scène, we are lured into a situation where we are at once voyeur and private sleuth. Her work is hugely haunting in its mien and rife with hungry ghosts we must negotiate at our peril in order to gain entrance and ensure safe passage though darkness. ❚

“The Missing Week” was exhibited at Galerie Trois Points, Montreal, from November 21 to December 19, 2015.

James D Campbell is a writer and curator in Montreal who is a frequent contributor to Border Crossings.