Natalija Subotincic

The exhibition “Chew Your Food Before You Swallow” included the results of artist/architect Natalija Subotincic’s recent architectural theorizing: the catalogue in an elegantly designed box with three books containing photographs of animal bones gathered from seven years of the artist’s meals neatly embedded in the surface of a hand-built table; drawings and commentary about Sigmund Freud’s study in Vienna, Freud at the Dining Table, described as an “architectural act”; and Subotincic’s architectural work on an expanded Museum of Jurassic Technology. Her collaborators on the museum project—the artist prefers that term rather than “clients”—are founders David Wilson and Diana Drake Wilson, the famous subjects of Lawrence Weschler’s best-selling Mr. Wilson’s Cabinet of Wonder.

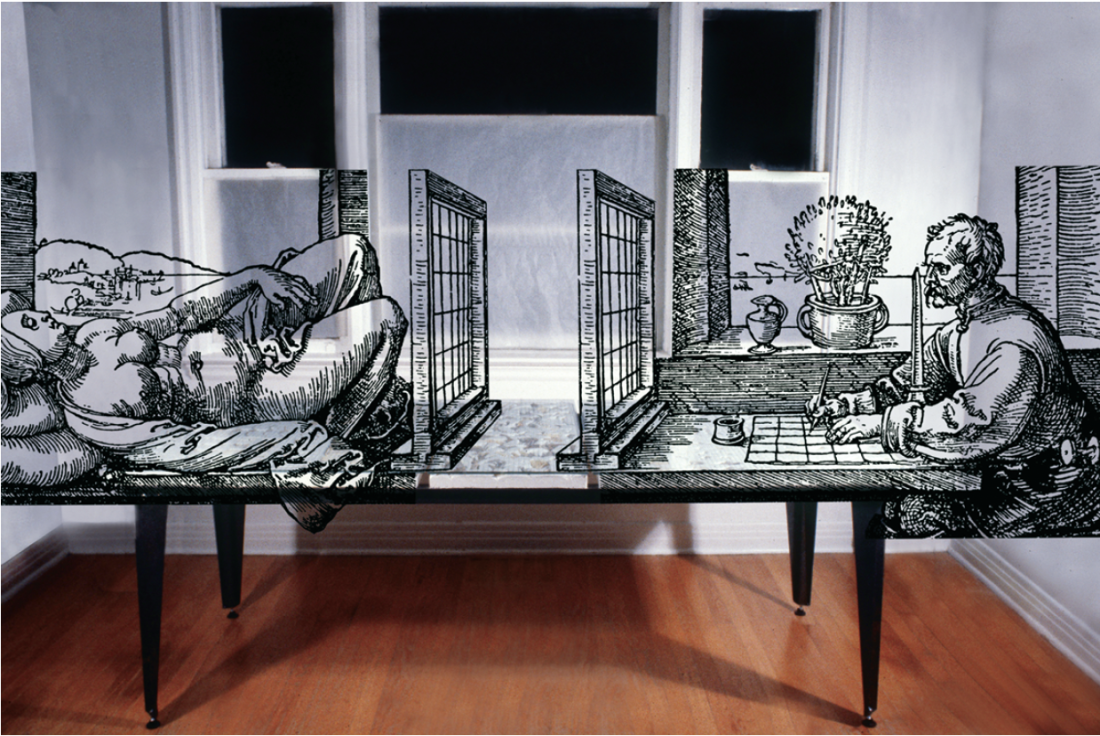

Natalija Subotincic, Bone Table with Durer, 2007, photo collage, 2 x 3’. Images courtesy the artist.

As a child, Subotincic would retreat under the dining room table during Sunday suppers; for her, tables connote secret, contemplative places. Her bone table mimics the taxonomical precision of natural history displays in the spirit of David Wilson, who also makes eccentric historical displays, or maybe Mark Dion, who does anthropological digs in riverbanks that are artistically but not anthropologically important.

“Museums by artists” has long been a category of art, and Subotincic is just such an artist. She “files” bones onto her tabletop by type “like a 19th–century naturalist.” Of course, nobody forgets that the 19th-century naturalist’s work is far from being complete: after all, even while advances were made, most species had not yet been catalogued, probably because they were bugs without the attractive features of furry mammals. But that is not to say that artists should become actual naturalists. Dion, Wilson and Subotincic are less interested in natural history than the museum itself and certain histories of its collecting that date back to the cabinet of curiosities era.

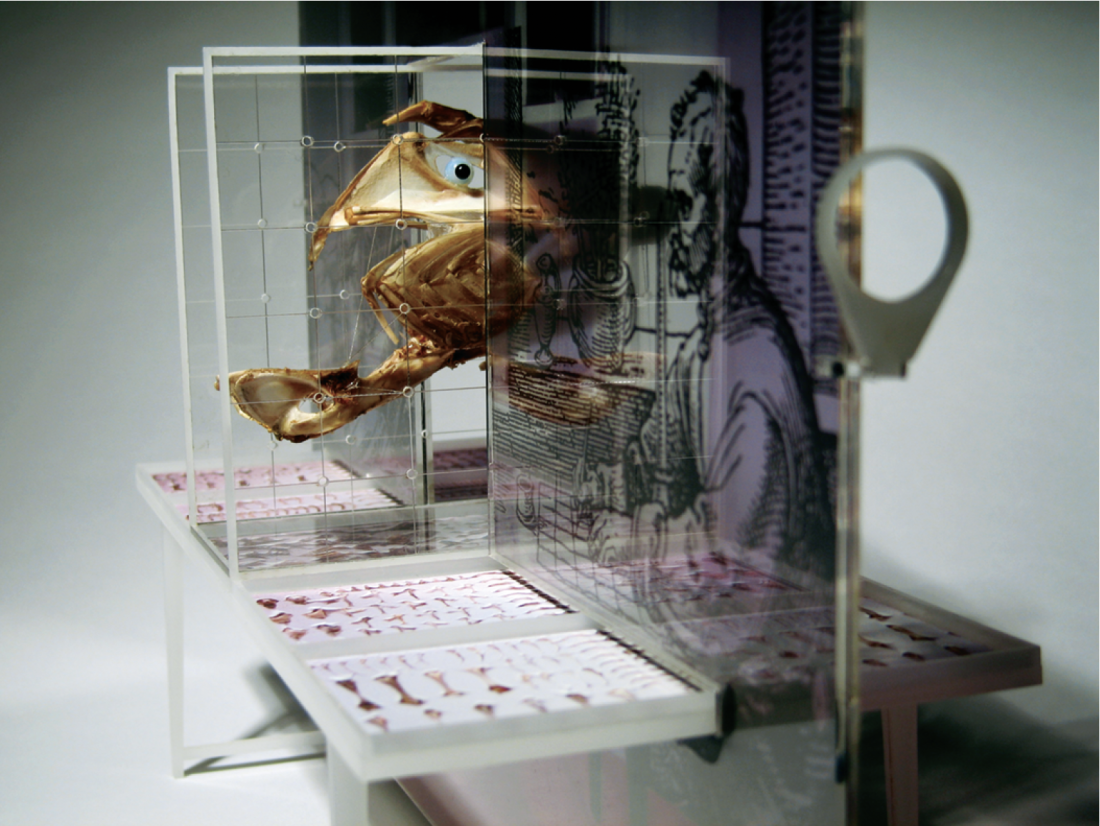

Natalija Subotincic, Model of the Cloister for the Museum of Jurassic Technology Architectural Proposal, 2006, millboard and Plexiglas, 24 x 24”.

Like Wilson, who built the Jurassic museum with displays that are sometimes biologically accurate but also always his own art (although he would be inclined to deny that), museums-by-artists artists fold the traditional museum over onto itself the way artists construct their own personal museum version of immortality. Traditionally, of course, serious artists did everything they could to preserve their work in museums, but the Wilsons and Dions and Subotincics nowadays go beyond that: for them the museum is the work. However much they pay homage to the careful plodding of naturalists, these artists are much more interested in their own fantastic categories and personal collecting inclinations than in actual science. Like her colleagues, Subotincic wants to make the natural history museum—and by extension the art museum—subject to her own theories of classification and explication, and built on her own personal taxonomies.

Natalija Subotincic, Bone Collection, 2008, black and white photograph, 11 x 14”.

Personal taxonomies are not about the discovery of new species but new perspectives on well-known things. In other words, Subotincic’s discoveries are entirely aesthetic. Her engagement with Freud, for example, returns the psychoanalyst’s clinical practice to the realm of culture where, by the way, many believe it has always belonged. She puts psychoanalysis on a level playing field with art, as does, for example, the performance artist/psychoanalyst Jeanne Randolph. Subotincic’s Freud work recalls complaints by Freudians about the “professionalization” of psychoanalysis as addressed by Janet Malcolm in her book In the Freud Archives. For many artists and even psychoanalysts, psychoanalysis is culture before it is medicine, and as such it is subject to artistic treatments, if not cures.

Sigmund Freud created a personal museum of over 2000 objects within the two rooms of his study in Vienna. Subotincic’s book Never Speak With Your Mouth Full, along with her Freud drawings, riff on Freud’s study as observed by the artist during her residency in Vienna. The book also addresses several women in Freud’s life, as well as Subotincic’s table. Subotincic reproduces architectural sketches by Freud in her catalogue. She means to subject the analyst himself to analysis by architecture; as she puts it, “his spatial organization of the room reflects his inner psyche.” So Subotincic means to turn the tables, if you’ll pardon the pun, on Freud and the museological remains of his practice.

Nattalija Subotincic, Bone Table Maquette with centerpiece, 2007, Plexiglas and bone, 1’ x 1’ x 6” x 7 years.

The turn in art toward Subotincic-style personal museology was prompted in part by conceptual art’s focus on art administration. Once the artist takes control of the mechanisms of distribution, preservation and museology, she becomes the custodian of a purpose-built museum that is part of an attempt to control and perpetuate the artist’s work on her own terms. It should come as no surprise that since Duchamp’s personal museum The Box in a Valise, it has been increasingly difficult for the critic and curator to override an artist’s own slant on their work. Once the primary sources include secondary commentary by the primary source, the artist herself, the fun really starts. ■

Natalija Subotincic’s “Chew Your Food Before You Swallow” was exhibited at the Arch 2 Gallery at the University of Manitoba from February 28 to March 28, 2008.

Cliff Eyland is a painter who lives in Winnipeg.