“MyWar: Participation in an Age of Conflict”

My computer opens up every morning onto the rocky international terrain provided by CNN, which means that before I’ve had my first sip of coffee I’m privy to whatever military and guerilla conflict is the most world-urgent at the moment (though today, civil strife in Libya got seconded by the cataclysmic earthquake and tsunami in Japan).

It is this war continuum that tinctures our lives. I have never lived in any war-torn area, but thanks to the Internet, those war-riven places live in me—and in all of us.

We teeter on the brink all the time, and the brink is like a cliff-face that keeps eroding toward a hundred continuing “micro-narratives of war” (the phrase is Paul Virilio’s in his book Pure War, 1983). It is almost with nostalgia for the albeit deadly clarities of the master narrative of World War ii that one encounters a text like Andre Breton’s, in Arcanum 17, 1944, where he dilates upon the degree to which he is protected from the “insanity of the hour” (the war in Europe) by hiding for three months behind Percé Rock in the Gaspé Peninsula. The cleanly defined, black-and-white war is not here; it is over there. And in the movies. You can take it, or leave it alone.

But our Internet war—sometimes a Photoshop war—is a constant, omnidirectional flow of war bytes passing though us without ceasing: an infestation, what Virilio calls “an intestinal war in the biological sense.” What we experience are the rhizomes of war, not its rhythms. What Deleuze and Guattari call, in On the Line, 1983, the pauseless intermezzo of continuing war events.

Oliver Laric, Versions, 2010, airbrushed plates.

How cathartically welcome, then, is this disturbingly searching, compassionately ordered, international exhibition “MyWar: Participation in an Age of Conflict,” organized by FACT, Liverpool, and the Edith Russ Site for Media Art, Oldenburg, Germany (in cooperation with ISEA2010 RUHR, Germany) and curated by Andreas Broeckmann, Heather Corcoran and Sabine Himmelsbach.

“MyWar,” write the three curators in the introduction to the exhibition’s catalogue, “approaches the theme of art and war through the lens of the new possibilities for engagement and involvement with the social communication platforms of the World Wide Net.” The art it presents, they make clear, “is not necessarily Internet based, but it appropriates the new style of an unavoidable, almost exhibitionist participation.”

The phrase “almost exhibitionist” is almost, in this context, shocking. You’ve shown us your favourite YouTube videos, they say, and your snapshots on Flickr and thrown up the faces of your friends on MySpace. “Now show us your war in MyWar.”

And the 10 participating artists do that. Oliver Laric, ironically developing further what were eventually shown to be Photoshopped missile-testing images released by the Iranian Revolutionary Guard in 2008, here, in Versions, harvests some of the Internet’s gleeful responses to the doctored missile photos and turns the threat into a kind of technophobic slapstick. Now he’s offering photos of not four but maybe 40 missiles, or, contrariwise, missiles absurdly aimed back at the launch site itself—like explosive boomerangs.

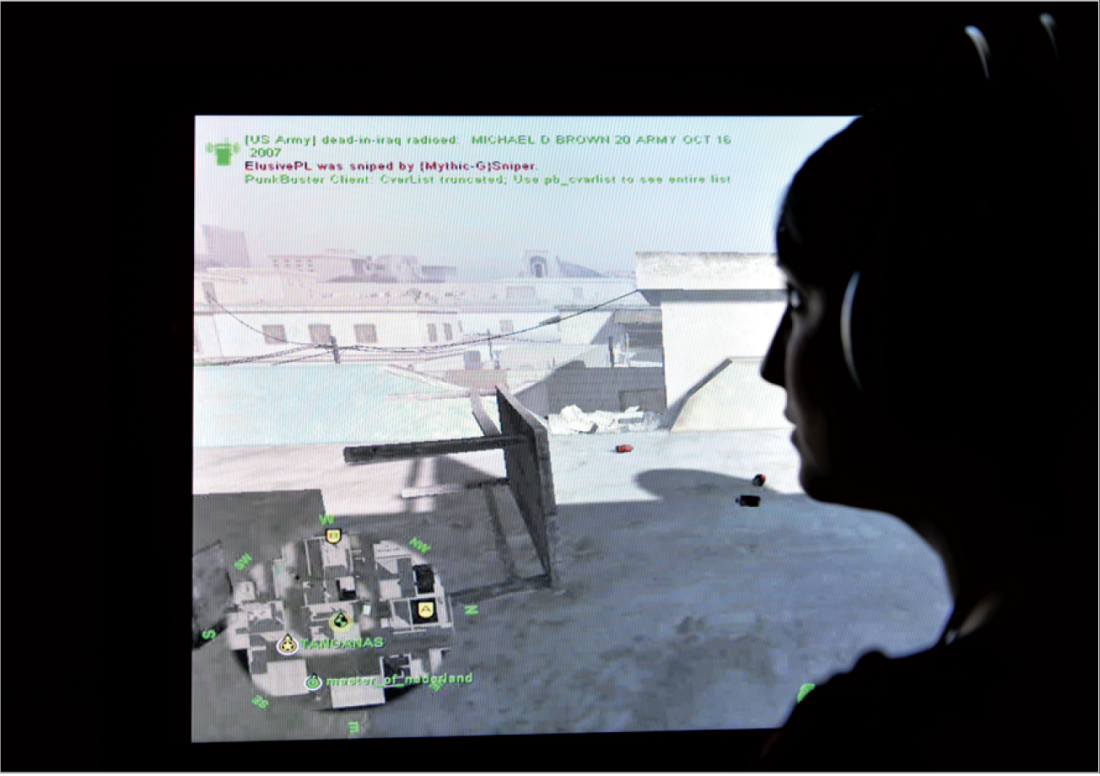

Joseph DeLappe, dead-in-iraq, 2006–ongoing, video, 18:55. Courtesy the artist.

The American duo called SWAMP (Matt Kenyon, Doug Easterly) contributed an example of their improvised empathetic device (i.e.d), a rather grotty-looking armband (electronics, duct tape) designed to bring the wearer to a literally painful awareness of the number of American soldiers actually killed in the Middle East. The device, ordered by a software application that continually monitors a website (icasualties.org), notes the personal details of each fallen victim (cause and location of death, etc.) and then alerts the wearer, to understate its effects, by driving a solenoid-powered needle into the wearer’s arm. “Pain is the data carrier that reconnects reality back to itself, bypassing the hyperreal spectacle of mass media.”

There is fine and shocking work here by the British team of Thomson & Craighead (A Short Film About War, 2009), by the Belgian artist Sarah Vanagt (Begin Began Begun, 2004), a 36-minute documentary about genocide in Rwanda, American Harrell Fletcher’s Humans at War, 2005–2010, an affecting drawing workshop for young students in Wisconsin, the drawings based on their overhearing personal experiences of war, and others about whom there is insufficient space here to write.

Something needs to be said, however, space or no space, about Dutch artist Renzo Martens’s brilliant and infuriating video work, Episode 1, 2004. Set in and around the Chechen war zone and its refugee camps, the piece follows the distressingly deadpan Martens—who is far more film-star beautiful than seems absolutely necessary—as he waltzes blithely into the camps with his video camera where, in a lethal parody of the trope of the concerned “personality” visit to the deprived and hapless, proceeds to ask these hurt, angry and depleted people searching questions like “What do you think of me?” and “Do you think I’m handsome?” And the thing is, nobody strangles him. Indeed a gaggle of middle-aged woman find giggly joy in how cute Martens is. The work may well go some distance towards “unraveling the hypocrisy of a global media system”—indeed it assuredly does so. But only if you can keep from hurling hard objects at the screen. ❚

“MyWar: Participation in an Age of Conflict,” curated by Andreas Broeckmann, Heather Corcoran and Sabine Himmelsbach, was exhibited at the Agnes Etherington Art Centre in Kingson, on, from January 15 to April 10, 2011, and the Union Gallery in the Stauffer Library at Queen’s University in Kingston, on, from January 15 to February 12, 2011.

Gary Michael Dault is a critic, poet and painter who lives near Toronto.