Music - Among a Lot of Other Things

All photos: Dave Barbour

On Saturday, April 23, the Winnipeg Art Gallery hosted a program of light and music organized by two composers: Diana McIntosh and Ann Southam. Called Music Inter Alia (Music, Among Other Things), the scope of the program was confined to Canadian works which “represent a wide variety of responses to the magic of sound and light.”

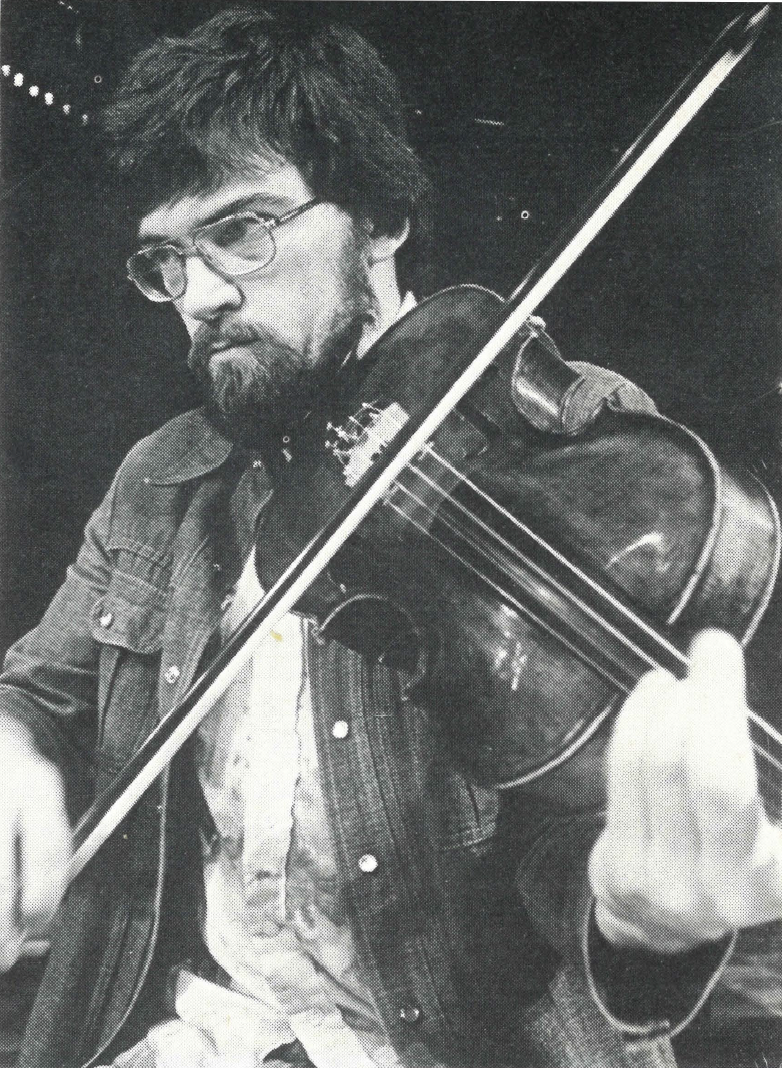

Ann Southam’s Toward Green, which opened the program, is scored for violin (Arthur Polson), viola (Rennie Regehr), flute (Jan Kocman) and clarinet (Ted Oien). The title of the work seems to suggest both its sprightly nature and its tendency to hover around the G-major triad. The musicians were placed at wide intervals across the front of the auditorium and the movement of the melody from place to place and timbre to timbre created the effect of a spatial fugue. At the opening of the piece, the performers had difficulty adjusting to the problems which the distance caused, so that the tuning lacked centre and the continuity of the melody’s movement was often interrupted. They nevertheless recovered remarkably, so that the sustained notes, which from time to time held the movement of the music in momentary stasis, almost visibly moved across the space between the players.

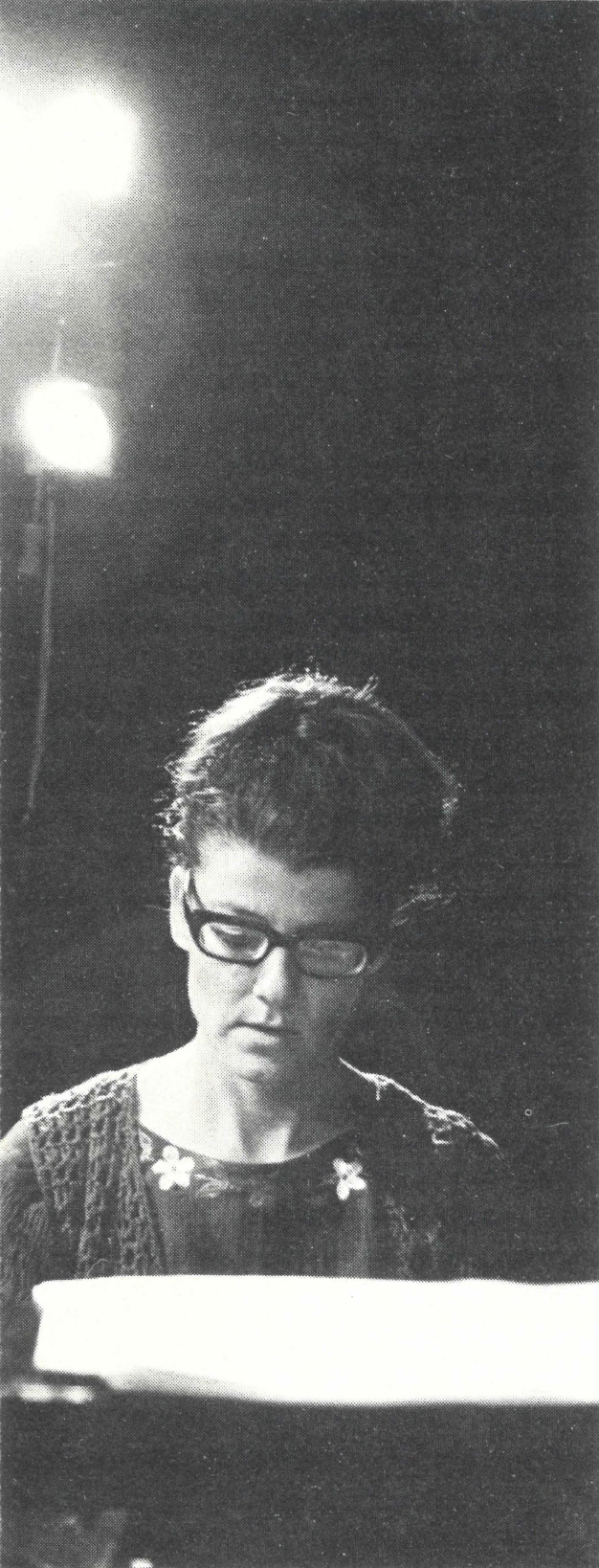

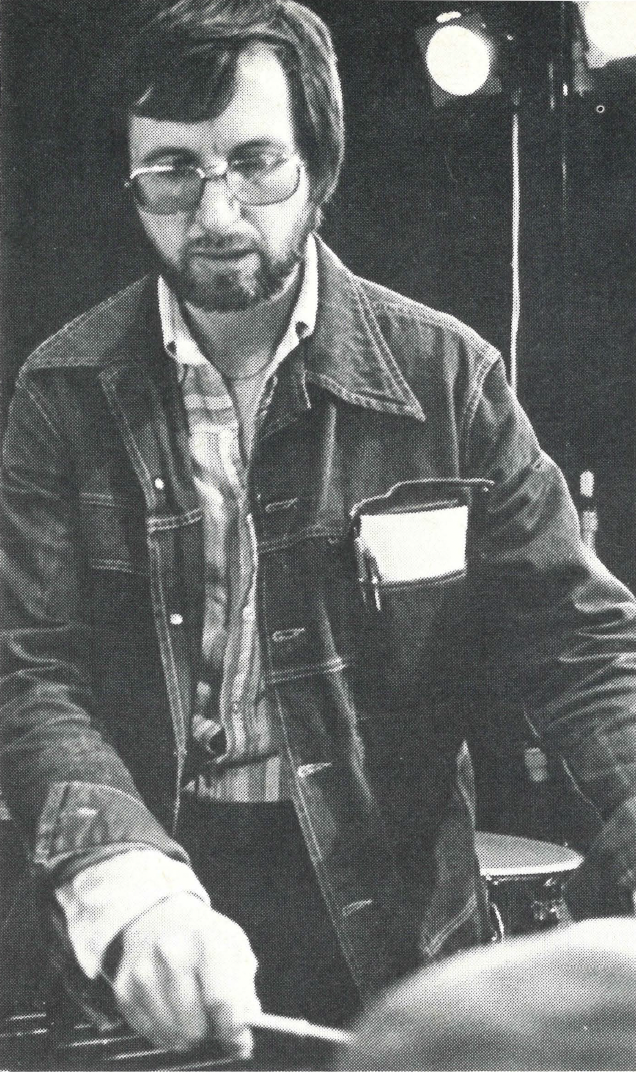

Vortices, written by a young Winnipeg composer, John Winiarz, disturbed me with its tendency to be at times highly programmatic and then obscure. Mr. Winiarz chose to accompany his electronic tape and lighting effects with an ensemble of percussion (Owen Clark), piano (Diana McIntosh), and amplified viola (Rennie Regehr). The work opened with the sound of wooden wind chimes (created by wood blocks) coming from both sides of the back of the auditorium, which moved forward as the tape gave the impression of stronger and stronger winds. An exceptionally effective thunderstorm of light and sound ensued. From there, however, the work ceased, for me, to be strongly programmatic (although a fellow listener said that it reminded him intensely of being in the trenches during the war — but then where do the opening wind chimes fit?). It tended rather to be an assault of wildly interesting sound and light, which seemed, contrary to the claims of the programme notes, to be fairly shapeless rather than eddying, yet was never-the-less effective. The performers used their instruments in a variety of ways, both expanding the potential sound repertoire of the small group and reflecting the tendency of modern composers to explore all the sonic possibilities of an instrument. The resonance of the viola was used percussively as well as melodically; piano strings were plucked as well as struck.

Both the music and the slides of Robert Daigneault’s Corridors were effective, but the coordination of slides and music was disturbingly poor. Spacious hallways of ivy-covered courtyards were juxtaposed with highly frenetic, stair-like motifs; while the calmer, more eerie portions of the music sometimes accompanied stairs photographed from disturbing, disorienting angles. Unfortunately, and perhaps this is an inherent problem of multi-media works, the fine photography projected on both sides of the auditorium eclipsed the music rather than fused with it. Because the slides were more accessible, the effect was to be intensely aware of the music only when it seemed to clash with the mood of the photographs. Only by vigorously ignoring the activity on the walls could I discern that Mr. Daigneault has written and shaped mood music that was sensitively realized, especially by the flutist, Jan Kocman.

In Mr. Daigneault’s other work on this program, Reminiscence, an ensemble of piano, clarinet and marimba again accompanied slides — this time of photographs from the 1940’s. The balance of interest between photos and music was superior to his other effort; although, again, there were conflicts between the mood of the slides and the music. Ted Oien’s dependably exceptional performance captured the sepia-toned nostalgia that was reflected on the walls.

In Peter Allen’s “Logos”, a mystically eerie composition for tape and piano, fine use was made of the textural differences between the live piano and the recorded material. Diana McIntosh’s performance seemed, however, to be hesitant and to not really reflect the architecture of the music and the tape. The result was the composer’s rather good use of temporal rather than rhythmic relations seemed often to disintegrate into a collocation of fascinating but directionless sound.

T-Ball-2, which involved tape and slides, is a collaboration between Vivian Sturdee and Ann Southam. The tape is of a tennis match that includes grunts of the players, declarations of the referee, and cheers of the fans. The slides moved one’s imagination into and beyond the tennis match as the tennis balls represented variously the players, movement, solar eclipses, and … fuzzy tennis balls. The second collaboration between Vivian Sturdee and Ann Southam, Les Oiseaux Reiurs (The Chuckling Birds) again combined slides and tape, but added performers scattered throughout the audience tapping stones together, whistling, or whispering bird names. The order of these performed events was, I discovered, clued by certain aspects of the slides. The juxtaposition of highly tinted drawings with gray-toned photographs of a prairie landscape was one of the work’s strengths. Another was the tape’s interpretation of the bird sound: I had always imagined that the emperor’s golden, immortal nightingale sounded that way. My suspicions, however, that the work was too long and provided too little variety were reinforced by a noticeable restlessness among the audience toward the end of the work.

I found Norma Beecroft’s Rasa III one of the least consistently effective works on the program. Rasas (the Sanskrit word for moods) attempted to suggest the nine moods which, according to Sanskrit theory, comprise the range of human emotions: erotic, comic, compassionate, heroic, cruel, terrifying, and horrid (the latter three were combined into a single movement), marvelous and peaceful. The ensemble of soprano (Barbara Goff), flute (Laurel Ridd), trombone (John Miller) piano (Diana McIntosh) and percussion (Owen Clark) is meant to react to the electronic tape along certain vaguely-defined parameters of pitch, sound quality, or time.

The most effective aspect of the ‘erotic’ section was the clearly-miked heavy breathing. The ‘comic’ movement was titilating, although, with the exception of John Miller’s really ingenious use of his trombone, much of the comedy was an extra-musical free-for-all between the pianist, soprano and percussionist. ‘Compassionate’ was rather too much like ‘peaceful’. The soprano dominated both movements, and either Barbara Goff’s emotional scope was limited, or the score failed to provide her with any real possibilities. I found the ‘heroic’ section particularly interesting: through the superimposition of groans and shots on the tape with little fife and drum motifs supplied by the performers, the music captures the often contradictory aspects of heroism. ‘Cruel, terrifying, and horrid’ imposed a lot of hair-raising screaming and sound upon the audience. It was effective, but I don’t know if I’d like to go through it again. ‘Marvellous’ seemed disjointed, and was only saved by Owen Clark’s really ‘marvellous’ use of a myriad of chimes. In general, the composer and the musicians realized the stronger moods or passions more effectively. The quieter, more peaceful sections tended to be pleasant, but nondescript.

Considering that Ms. McIntosh and Ms. Southam imposed two limits upon their selection: that the music be Canadian and that it explore more than the single medium of sound, the music of the program was of exceptional quality. A particularly wise choice was to open the concert with Toward Green, largely because the repetition of the material allowed us to become familiar with it: we had, by the end of the piece, grasped and comprehended what at the outset seemed alien and chaotic. The more light-hearted works for slide and tape offered respite for minds which were working at grasping new concepts and accepting new sounds.

Most of the audience seemed to enjoy their experience, indicating perhaps that there is further need to explore and perform contemporary music — perhaps on a local as well as international scale. There is an equivalent need to learn how to listen to the new music and concerts of this nature and calibre can indeed make the learning process enjoyable.

Concerts of contemporary music also give us an opportunity we don’t often have: they transform us into those seventeenth and eighteenth century patrons who supported and believed in composers like Bach, Mozart, Haydn and Beethoven, without whose music our concert halls would seem barren.

Murmurs among the listeners again and again reiterated the problem audiences have with any modern art form. It was fun they said, but was it music? Well, no; some of it was music and some of it was merely art.

Kathleen Wall writes the programme notes for the Manitoba Chamber Orchestra. She is a free-lance editor and music freak.