Mountain Man

Simon Hughes’s one-person exhibition opened on March 5, 2020, at the Peel Art Museum and Archives in Brampton, Ontario, and closed a week later due to the coronavirus. The gallery, smartly, has decided to continue the show through October 12, which is a good thing, since the work deserves a large audience. What is surprising is that the exhibition is his first in a public museum. Curated by Sharona Adamowicz- Clements, it is a two-decade-long survey of 40 drawings and paintings that covers all the bodies of work he has produced since 2001, including his Utopian Architectures, the ice floes, the California Native series of potted desert plants, the Mountain paintings and the Artists’ Studios.

Hughes’s art is acutely aware of its own making, which is one of the reasons he is attracted to the theme of the artist’s studio. The most famous painting of this subject is Matisse’s Red Studio, 1911, and Hughes made three watercolour versions with the same title. He recognized his identical naming as “a brash move doomed to failure,” but his admiration for Matisse—“the saturation of the cadmium red is amazing”—made him “go for it anyway, just to see where it lands. It was a technical exercise to get to that level of redness using transparent paint and absorbent paper and it was also a bit of a joke because Matisse’s painting is very spontaneous, the wallpaper is just a few little squiggles and it feels very painterly, but my version is incredibly regimented and drawn with a T-square.”

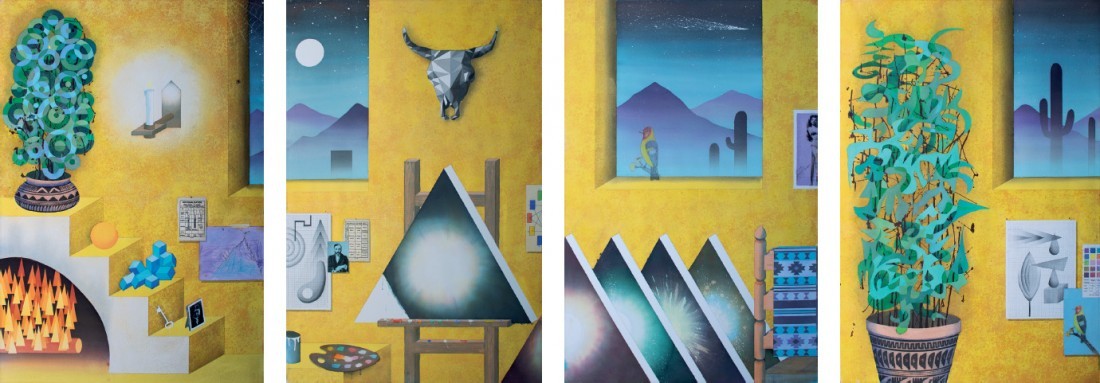

Gold Studio, 2019, watercolour, coloured pencil, acrylic, graphite and acrylic Xerox transfer on paper. Four panels each 57 x 37 inches. All images courtesy the artist and Galerie Division Montreal.

His other studios take on a different palette; Gold Studio, 2019, is an imagined version of Lawren Harris’s New Mexico studio, circa 1934. Black Studio, 2016, and Blue Studio, 2017, are not as specific in their sense of art history, but what they share is the ability to describe a space that is both physical and imaginative: “Whenever a painter does a painting of the interior of their studio, it is always the interior of their mind.”

The Mountain paintings function in a similar way. “The mountains are meant to be a CAT scan of my brain and all my desires and thoughts,” Hughes says, and he has characterized the range of that scan as moving from “the humble to the heroic.” One of the best measures of that function is visible in the sculptures he includes in his series. On the basis of number of appearances, his favourite sculptor seems to be Henry Moore, but his high and low preferences tend to be equally distributed: Smokey the Bear, Mount Rushmore and Paul Bunyan and his blue ox, Babe, are as likely to turn up as the Sphinx, the Minoan Snake Goddess and Picasso’s Bust of a Woman from 1931, his exaggerated portrait of Marie-Thérèse Walter. In his compositional strategy things are treated equally. “Mount Everest is given the same heft as a small snowman,” he says. “Or you might recognize the Matterhorn, which is a colossal object, but then it is juxtaposed with a tiny pre-Colombian statue that is only two inches tall but that I make giant. The scale gets all out of whack.”

Red Studio, 2014, Watercolour, coloured pencil, gouache and acrylic Xerox transfer on paper, 3 panels, each panel 58 x 38 inches. Claridge Collection, Montreal.

The paintings are filled with architectural images, birds and forms of transportation, but what mitigates their presence is Hughes’s tendency to integrate the collage with the painting. “The goal was to blur the line,” Hughes says, “to paint over them in a transparent way where the found imagery doesn’t appear to be just glued on.” In a four-part painting called The Uncanny Valley, 2018, he works in a complementary palette of cool greys and blues; #2 has the usual assortment of real and painted mountains, as well as vehicles and snow huts. As it rises, the mountain’s colour shifts from blue to white, and just below the summit a pair of intertwining lovers carved in plaster or stone rests in place as if they were undulating formations of snow. The tonal and rhythmic blending is immaculate and the sculpture reads as topography as much as figure. It embodies the idea of the blur and renders what could be an awkward juxtaposition into a seamless space. In other paintings in the series, he will organize the composition around a visual idea, so Mountain (falls) from 2019 employs images of waterfalls and vertical rectangular shapes as a way of reinforcing the formal dimensions of the painting.

Hughes compares his method of composing to Dada poem making, “where you randomly pull the words out of a hat.” These chance encounters can be risky, and he is aware of the possibility of falling over the image precipice. Mountain (magma), an acrylic on linen from 2019, is an accumulation of close-valued red and orange shapes arranged to form one of his signature mountains. A collection of figures, structures and statues are placed in many of its faceted segments, including a Minuteman holding a rifle; a statue of Billy Graham taken from the grounds of the Crystal Cathedral, the megachurch designed by Philip Johnson for the evangelist Robert Schuller; and a photograph of Marilyn Monroe vamping it up as the silent film actress Theda Bara, taken by Richard Avedon in 1958. To counteract the painting’s becoming “a heavy-handed statement about a reactionary westward expansion,” he added a cluster of other images, including the Sphinx and an image from the hell section of Hieronymus Bosch’s Garden of Earthly Delights. Hughes says, “The painting teetered on the edge of some clunky associations that I wouldn’t want, so I pulled it back, but you have to go to that edge. Nothing is off limits, but there is a point where I try to rein it in and not have it get weird for weird’s sake.”

Mt. Zammett, 2018, acrylic and collage on linen, 78 x 102 inches.

Hughes’s inclination is less towards the weird than the wily. When he calls a landscape Reaction Formations, 2017, he is calling attention to the method he uses to compose; the forms he chooses are reacting to one another and the accumulated effect of those reactions determines what the composition becomes. The phrase is a lift from Freud’s discussion about overcompensation, but Hughes applies it to the way his paintings work on us as viewers, and on him as a maker. “In psychiatric terms a formation is a mental construct, but the beauty of it is that formation also applies to geology. When I heard the term it was like a perfect two-word manifesto for what these paintings are more or less about: it’s a bull’s eye for seeing landscape forms as some kind of bizarre MRI scan of your brain. When you combine the inner and the outer in the landscape, what you come up with is actually the landscape inside your own head.”