Monica Tap

Monica Tap’s paintings capture immediate impressions of the landscape under differing climatic conditions—from hot to cold, dry to wet, bright to dark. This inevitably leads to dialogue with the mythologized history of avant-garde attempts to do justice to changing light and weather, as in Monet’s “Rouen Cathedral” series, 1894, to take one especially venerated example that, like Tap’s project, has photographic qualities. However, her work critically strays from the forms of passive sentimentalizing that follow from such dialogue—just think of Monet posters, or an infinitude of digitalized Monet’s online—by injecting a decentred and disoriented subjectivity into the mix.

Is it late summer or early autumn? Fluctuations in temperature, light conditions, atmospheric pressure or moisture levels sometimes do not allow for a confident designation of the season, despite conventional calendrical divisions: fall’s first day is, we are told, September 21st. Such ambiguity sets the stage for Tap’s series of four seasonal paintings—all completed in 2009 and exhibited in 2010 at Wynick/Tuck Gallery in Toronto—based on stills extracted from low-res video, captured in moving vehicles using the video feature on her cell phone. These works are partly about the failure of both technology and humanity to represent—in the face of media—cultures that are moving faster by the minute, like a train without a conductor.

Between Summer and Winter features a group of trees, rendered predominantly in grey with moss-like details on their trunks. Less identifiable are motifs that may refer to branches, given their length and horizontal orientation, but that is where the direct resemblance ends. Composed of layers of cream, yellow and orange—which may signify the separate colour values that the camera is unable (or unwilling) to blend into a more mimetic and seamless whole—these fluffy cloud-like or smoggy strata register as artificial in tone and possibly toxic in content. And they are too prevalent within the picture to come across as a mere minor mechanical mistake. Rather, they reflect a systematic inability to represent under the duress of speed or other unknown forces.

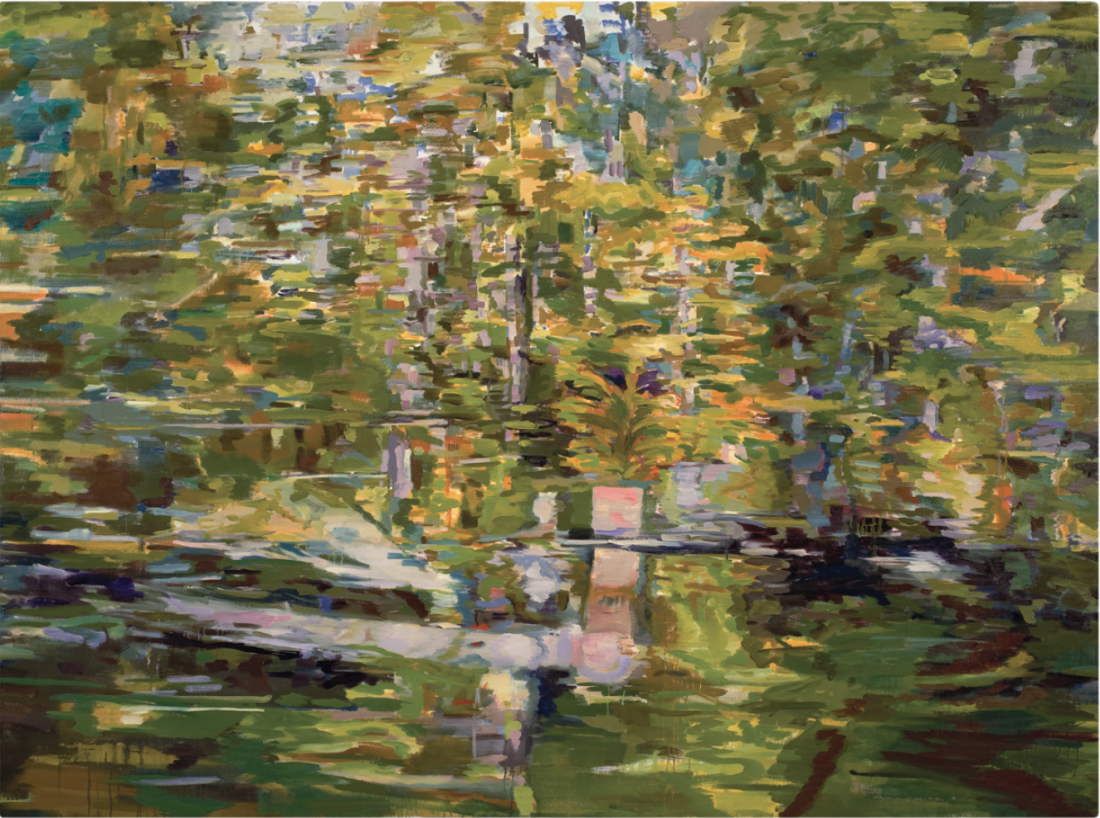

Monica Tap, Between spring and fall, 2009, oil on canvas, 60 x 80”. Photograph: Rick Johnston. Courtesy the artist.

Between Spring and Fall kindly offers an expanse of green that may suggest summer, but Tap strives to survey the seasons as though they were undergoing a deconstructive predicament—a process that may radiate heat, resulting in the drips in the work’s lower regions. Rather than by smog, the camera’s strain is expressed by patterns akin to camouflage, as well as a rectilinear and vaguely architectural shape, set apart from the forested background; these “mistakes” are joined by a circular body with a comet-like trail emitting white exhaust. For me, such unseasonable imagery subjectively signifies states of reverie akin to the half-conscious stupor felt during prolonged stares out of speeding train windows.

Between Fall and Spring dutifully and doubly depicts leafless trees, both above water and reflected in an icy pond. Along with such comforting signs of winter, I detect further failures of the camera’s descriptive capability: a rectilinear shape infused by an unwieldy brown and green form, perhaps a tree trunk. This picture within a picture refuses to comply with the horizon in the primary image, as though it arrived late or early. I speculate that this is a sign for fall or spring, for a previous time, or for a storehouse of seasonal memory. My insight from (rather than mere sight of) this thing is the result of Tap’s ability to broaden, abstract and complicate a sense of temporality, in which the past and present are fluid rather than static. This dynamic diversity is enhanced by the work’s textural variety, ranging from smooth to crusty, which simultaneously denotes the here and now of natural terrain seen from a train and exists as a buffet of painting methods in themselves. In addition, Tap employs colours that often exhibit a fidelity to the real and yet register as separate and readymade chromatic values—straight from the tube, as it were—that sometimes are not allowed to blend.

This ambivalence to verisimilitude is undoubtedly dictated by limitations of the software on Tap’s cell phone camera. But these works lead back to the idea of temporality coming undone and broken down into individual units that may refer to individual sensations—of light, colour, form and atmosphere—and the ways they become exposed and subjected to media. Such exposure affects even our most innocent and everyday perceptions, like picturesque scenery seen from a bus. Tap’s landscapes thus inhabit a space that is a long way from those composed strictly according to the humanist and rationalist traditions—dating back to Claude Lorrain’s 17th-century pictures with staggered terrain and recessional progressions, suitable for civilized contemplation in a manner that reinforces the ideology of humanity’s control over its surroundings. Her practice may be seen as a reflection on what it means to lose this control while still striving to maintain a palpable sense of wonder and beauty. ❚

“Here and also elsewhere” was exhibited at Wynick/Tuck Gallery in Toronto from April 10 to May 1, 2010.

Dan Adler is an assistant professor of art history at York University in Toronto. He is currently working on a book manuscript about sprawling, sculptural art exhibitions.