‘Molatham’ by Scott Caruth

Photographic portraiture is both the representation of an individual and a generic form through which the viewer identifies with both singular and generalized human experience: the beloved, the martyred, the criminalized. Inside the archive the singular character of the photograph dissolves into typologies of characters. Split and categorized by organizational hierarchies, the subject of the image and often the image maker are placed in relation to the rest of the collected materials. Once rendered a “type,” the identity of the subject of the portrait is produced externally through its relation to its associates. This dialectical procedure, integral to the function of the modern archive, was canonically theorized by the photographer Allan Sekula in his essay “The Body and the Archive” (October 39, Winter 1986). Sekula writes, “We are confronting, then, a double system: a system of representation capable of functioning both honorifically and repressively. This double operation is most evident in the workings of photographic portraiture.”

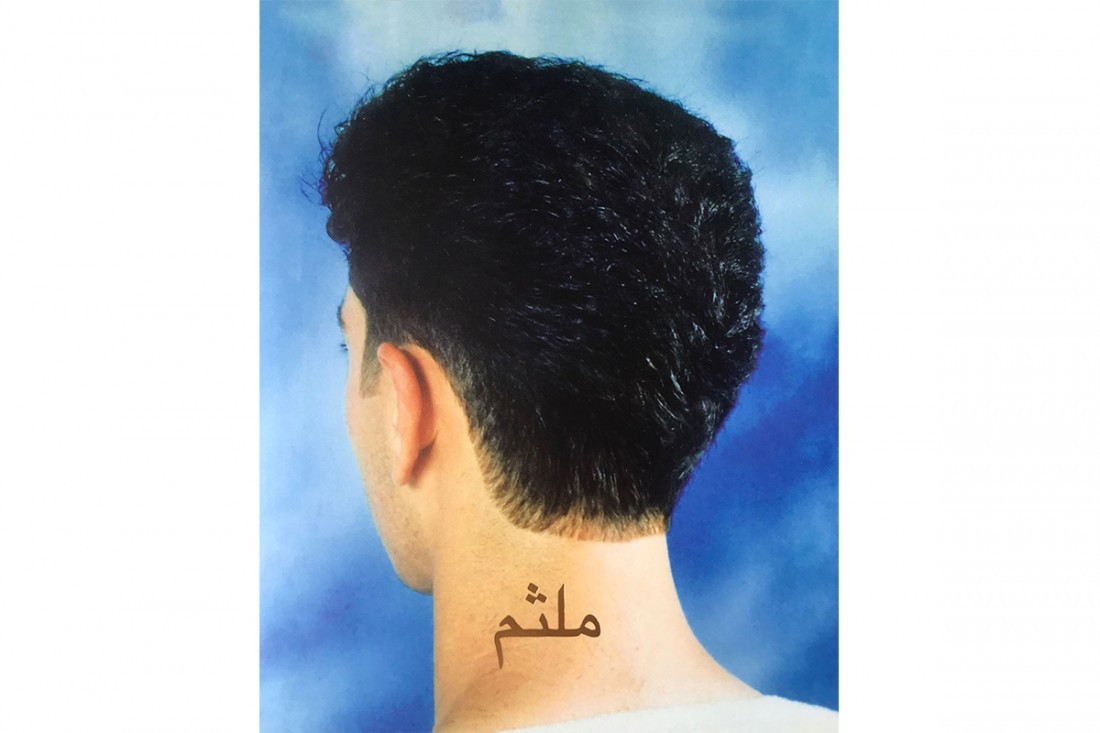

Photographer Scott Caruth’s first monographic work , Molatham, published by Trolley Books, is an archive of the social practice of studio portrait photography in the Palestinian West Bank, and a personal account of research conducted by Caruth in Palestine over a period of six years. Encompassing commercial studio photography, martyr posters and prison photography, Caruth’s project addresses questions of representation, subjecthood and citizenship. The direct Arabic to English translation of “molatham” is “to cover one’s face” and is used in the vernacular to describe the act of a Palestinian resisting Israeli arrest. It is under this banner, which acknowledges the double bind of representation identified by Sekula, that Molatham contributes to a field of discourse on the role of documentary in the defence of human and civil rights.

Molatham is a thick photobook with an unfinished binding, made up of essays, interviews and uncaptioned photos; it maintains an impression of handmade compilation— tactile and gathered. Indeed, the project is inscribed with Caruth’s hand and perspective; the introductory text details his political and humanitarian work with the International Solidarity Movement that led to his research on photographic studios. Caruth invites his readers to navigate the material and situate themselves within it. Taking this direction, the reader thumbs through a collection of textual and visual representations of encounter: Caruth in dialogue with the owners of Studio Ghari and Studio Chaplin, with images from those archives of their clientele and the photographers themselves. Further in the book: soft-focus images of Palestinian men (the photographs are almost all of men) posing with weapons, a live snake, flexing their muscles or simply against a background of their choice. The text and images come together in an aggregate portrait of what it means to live an urban life in Palestine today.

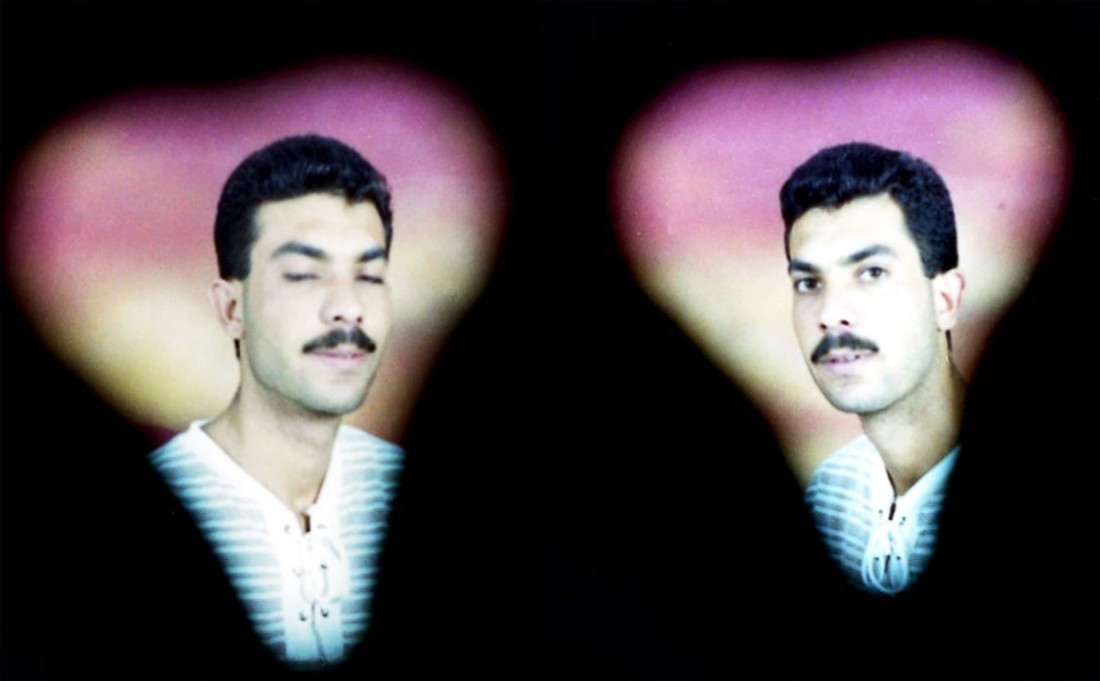

Some of the most striking photographs included are serialized images of Israeli Defence Force (IDF) prisoners over a period of years. The photographs document teenage boys aging into young men inside a prison, each image suspending its subject on a contextless background. In the accompanying essay on the iconography of prison photography, Caruth writes: “In an odd replication of the dynamic of studio portraiture, each year that a detainee is incarcerated is marked by the production of a studio portrait within the prison itself. These photographs are taken by the IDF on an annual basis and are sent to the detainees’ families and communities, reducing their relationship with them to one with a photographic object. The white backdrop, unchanging from year to year, presents the spatial and social limitations imposed on the subject’s experience over indefinite, endlessly extendable periods of time.”

It is in part the formal starkness of these photographs that renders them so beguiling. They are less adorned than the commercial portraits that precede them, and less obviously constructed than the martyr posters that follow them, although an edited image of the young men superimposed on an urban backdrop, and made by a graphic designer who specializes in these posters, is also included in the book.

The seriality of images of the young men in incarceration forces a reckoning with the function and conventions of photography in the Palestinian context. The historian and theorist most prominently associated with photography of the Palestinian/Israeli conflict is Ariella Aïsha Azoulay. Caruth directly engages with Azoulay’s writing, specifically her book Civil Imagination: A Political Ontology of Photography, published in 2012, one year before Caruth first travelled to the West Bank. For Azoulay, “the event of photography” is characterized by multiple temporalities of encounter. As she wrote, “the first (encounter) occurs in relation to the camera or in relation to its hypothetical presence while the second occurs in relation to the photograph or to the latter’s hypothetical existence.”

Here, in these prison photographs, a tension emerges between photography theorized as an apparatus, as suggested by Sekula, and photography understood as fundamentally performative, as argued by Azoulay. In Azoulay’s theory, the liveness of encounter opens up a space for understanding portrait photography not just as an agent of surveillance, categorization and representation, though it is undoubtedly all of those things, but also a ritualistic aspect of urban culture, part of the “civil imagination,” as she phrases it. It would do Caruth’s project a disservice to centre it inside a debate on photography that has been extensively argued elsewhere, but to consider the tension between a theory of representation versus a theory of performativity inside the photographic document may unbind some of the meaning and intention of the book, which lie in the question of subjectivity. Who, or what, are these young men the subjects of? Palestine? The IDF? The institution of photography itself? And how are we to answer that without committing to some level of participation?

In my flicking through and flipping back the photographs in Molatham, the subject of the Palestinian citizen emerges as a composite image, part of a social text produced through participation in cultures of self-representation as much as extra-territorial documentation. There are no spectacular images of suffering or any scenic depictions of an idealized population under siege. By sinking into the archival form, Caruth brings forward the ambivalence and universality of the photographic portrait. This is also true of the accompanying texts, where accounts of the First Intifada are given as much page space as an exchange about a can of Sprite. There is no naturalizing humanitarianism in this book; it is a document of how people appear in the public sphere. Molatham frames that performance: lives represented, lives assembled. ❚

Molatham by Scott Caruth, Trolley Books, 2019, 152 pages, paperback, £25.00.

Alexandra Symons Sutcliffe is a writer, curator and producer based between Berlin and London. She is currently a PhD candidate in the History of Art Department at Birkbeck University, working on British portrait photography of the 1970s and 1980s.