Miroslav Tichý

Miroslav Tichý was born in 1926 in Kyjov, a small town in Moravia, where he studied and practised as a painter until he ran afoul of the communist Czech government, and was jailed as a subversive. What transgressions Tichý was guilty of remain unclear, other than being “different”—but as repressive states go, he was enough of a threat to warrant incarceration. Enduring physical and mental abuse, Tichý spent time in and out of prison camps and mental hospitals for nearly a decade.

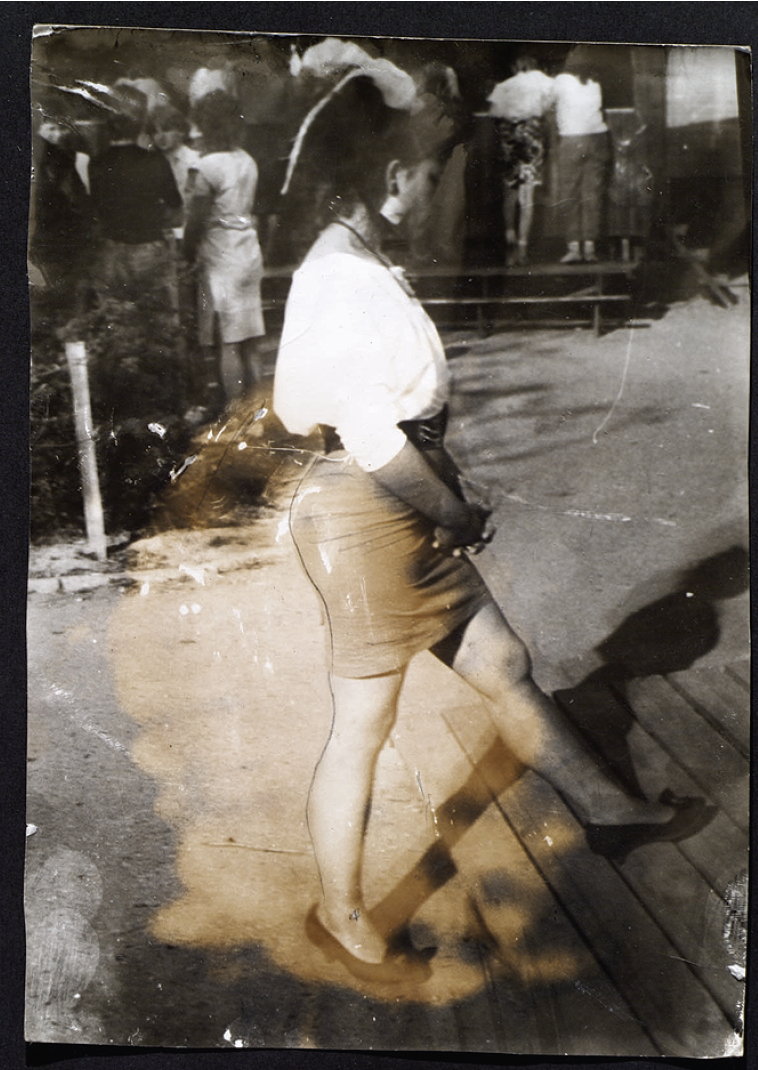

From the 1950s until the mid-’80s, he took up photography. Clad in rags and living like an ascetic in self-imposed exile on the outskirts of town, Tichý wandered the streets of Kyjov with the goal of shooting 100 images a day, and it was from this period that we see images and a methodology as idiosyncratic as the man himself. Using cameras cobbled together from junk such as cigarette tins, bottle caps, rubber bands, and toilet rolls, with spectacle lenses ground and polished with toothpaste and ash, Tichý created a body of blurry, scratched work, bearing hand-drawn embellishments and bromide stains, and mounted on stray bits of cardboard. His images have an ethereal and almost timeless quality about them, with an aura similar to the work of photography’s early pioneers such as Nicéphore Niépce and William Henry Fox-Talbot, where figures disappear into the grain.

Only a small part of the work on display gives us a glimpse of pre-Havel Czechoslovakia, and, overall, there is one important detail to the bulk of his work: Tichý loved women. So much so that he ventured into town to shoot rolls and rolls of photographs of them in parks, on the street, at the swimming pool, all on the sly with his handmade cameras. More flasher than flâneur, he shot from the hip in the same hectic and voyeuristic style of Gary Winogrand or a more hentai Daido Moriyama, but with a blatant expression of the secret leer and the stolen glance.

Miroslav Tichý, untitled, gelatin silver print. Courtesy Foundation Tichý Oceán and Presentation House Gallery, Vancouver.

Looking through Tichý’s lens, there’s no polite way to say it—his pictures, while raw and dreamlike, are, quite frankly, kinda creepy. However, Tichý has madness and the position of the amateur on his side, in that the works don’t have any built-in pressure to succeed, and since these works were selected from a haphazard archive of tattered images covered in dust and mouse droppings, kept stacked in cupboards or piled on the floor, (that were, so the story goes, never intended to be exhibited anyway), it seems that the images themselves become secondary to the mythology.

Of particular interest is how the biographical aspects of Tichý’s life—a ramshackle camera in a vitrine and the half-hour documentary on view in a corner of the gallery—seemed to draw the most interest. Here we are treated to Tichý, the bearded, toothless savant, holding court, quoting Schopenhauer and Kant about the illusory nature of reality and the beauty of imperfection as he takes us on a tour of his cluttered, filthy grotto. It’s a dysfunctional, but still romantic, version of the archetypal crazy-genius bohemian.

His photographs are made compelling through the filter of his life story and resultant persona. Paradoxically, and in all honesty, the images are rather unremarkable, but when you factor in the obsessive, even pathological approach to his subject matter, it serves to activate the work, so that they warrant a second look.

Miroslav Tichý, untitled, gelatin silver print. Courtesy Foundation Tichý Oceán.

Given his subject matter, I sense that many will dismiss Tichý’s photos out of hand on ideological or gender-based grounds. To do so would be too easy because it’s too obvious. Let me put that another way. In the context of contemporary photographic discourse (especially here in Vancouver, where a photograph is rarely just a photograph), issues of gender and representation are among numerous considerations that are part and parcel of reading a work. In this instance, though, one could presume that while parts of the art-world audience were reading Susan Sontag’s On Photography and learning about “the male gaze,” Tichý was being beaten by prison guards. Does this excuse him? Well, as a product of his own environment, Tichý wouldn’t apologize for it. He could be viewed as a man broken by state violence, operating from behind his circumstances—the show’s curator certainly seems to, and the attendant documentary works hard to create a sympathetic character, and to represent Miroslav Tichý via the trump card that the fellow is clearly bonkers.

It’s worth noting that his methods led to nuisance complaints against him from the townsfolk and more brushes with the law, revealing the photographs on view for what they are: selections from the private archive of a man who hid behind bushes in the park, furtively snapping pictures of sunbathers. If you begin to look at the work through his eyes, all Eros begins to drain away, leaving images that could stand up as evidence in court. Beyond the charm of a toothless smile and a snappy aphorism, Tichý still strikes me as a dirty old man. If you’re into this sort of thing, let’s get Freudian (or perhaps Dr. Phil) for the sake of argument: Tichý’s art seems less to do with things like content and more to do with fetishism and compulsion, the lens acting as a stand-in for the phallus, using voyeurism to pursue and exercise a sense of power over his subjects through the satisfaction of sublimated libidinal drives. (Or something.)

Given our tendency to see things through the filter of our worldviews and morals, it could be difficult to let Tichý off the hook—but, all things considered, he can also be seen as not guilty by reason of insanity. Tichý definitely takes pictures in the way that we steal glances, but he’s also a lone character who worked in his own Henry Darger-like realm, at the top of his own invented craft, aesthetically far removed from the Leica and Hasselblad set (although he’d be a shoo-in for the Holga and Lomographic crowd), with an irreverence that seems way more practical than contrarian. Ultimately, Tichý strikes me as a Czechoslovakian R. Crumb with a camera instead of a pen: he’s an oddball in touch with his drives and out of touch with the art world’s applicable discourses, who creates transgressive, even disturbing work, while using a disarming charm and outsider status to his benefit. Objectionable content or not, his work, like most art, is subject to our projections. And he probably wouldn’t care either way. ■

“Tichý” was exhibited at Presentation House Gallery in Vancouver from November 18, 2006, to January 14, 2007.

Christopher Olson is studying in Vancouver.