Mira Schor

Looking back at journals or artworks made as a student can be painful as well as nostalgic, exposing a soft underbelly, ideas raw, not yet finessed. But examining such material reveals the groundwork laid in those early days for what followed. “California Paintings: 1971–1973,” an exhibition of Mira Schor’s early works, many never exhibited before, or not since her MFA show at CalArts in 1973, reveals the foundation of Schor’s practice and maintains their relevance nearly 50 years later. The “California Paintings” here map Schor’s progression as a graduate student, to the completion of her MFA at CalArts in the early 1970s, where she enrolled in the now-legendary Feminist Art Program before she herself became a respected feminist painter and writer.

One year out of her art history degree at NYU, she moved to California, aged 21, having never been to the state before (a friend described it to her as “another country”). Growing up with two artist parents in New York City (her mother, Resia, and her father, Ilya, both multi-talented and working across painting, jewellery, silversmithing), Schor was privy to the daily practice of creating, with both parents working from home. She was also, presumably, aware of the prejudices within the New York art world, specifically those against craft, narrative and gender. The large array of works in “California Paintings,” almost exclusively gouache on paper, demonstrate a young artist finding her form, her themes and her language from this nascent stage in a formative period for the artist, as well as a time of great ferment culturally and politically.

Mira Schor, Car Triptych (Part I), 1972, gouache on Arches paper, 30 x 22 inches. All photos: Charles Benton. All images courtesy the artist and Lyles & King, New York.

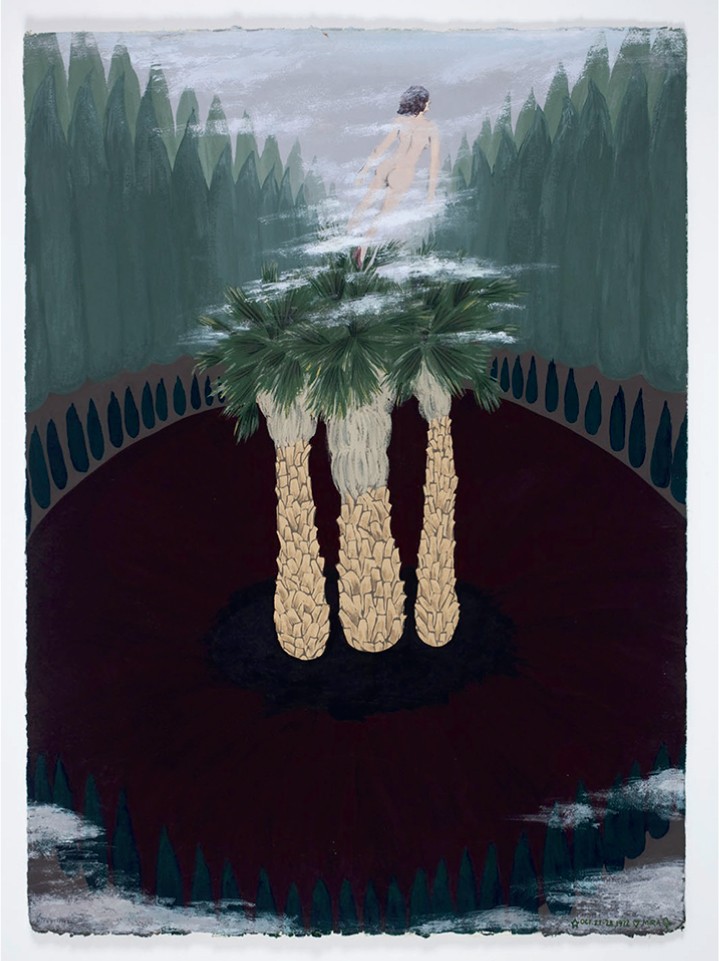

Schor’s visual language in this time is wide-ranging: from Warholesque high heels with pointed toes, positioned in profile, some against a backdrop of an endless highway, to female figures lying in bed hovering above the landscape (surrealist Leonora Carrington was an influence), to the flat melding of figures and landscapes of Rajput paintings. There are recurring spiky succulents, moons and twinned young Miras. The landscape of Schor’s experimentations is distinctly California—palm trees and sunsets on dense painted surfaces that read like stage flats, providing layers of imagery. Gouache on paper was not considered serious painting in the 1970s. (Schor didn’t turn to oil until the 1980s.) Reflecting on the doubts she had to overcome in the course of her time in California, Schor writes on her Instagram feed: “In plain terms, small, narrative, gouache, paper did not denote painting at that time, period.” Against the west coast sunsets, animals often appear both threatening and protecting. Cats are frequently next to the female figures, and a pack of wolves stare down two twinned, naked female figures who stand with their backs to the viewer, hands on hips in Car Triptyc (Part I), October–November 1972. In Bear Triptych (Part III), March 1973, a naked female figure and a bear are locked in a circular embrace that is more erotic than attacking (and this was painted three years before the publication of Canadian writer Marian Engel’s Bear). Both triptychs evoke storyboards or filmic sequencing.

Schor, who is arguably as well regarded for her critical writing as she is for her painting, posted excerpts on Instagram from personal letters that she had sent to her close friends. In one to the painter Pat Steir, dated 28 October 1971, Schor writes: “My dorm room is very nice and big, on the top floor, with a view of a golf club (don’t knock it though, it’s the only green for miles and the water in its ‘duck’ ponds are the only water for miles), all around are beige hills for miles, and the ever present freeway.” The arid landscape and the constructed environment collide, and Schor, reflecting in a letter to Ben Sonnenberg from 7 November 1971, writes that her “brain still holds the sound of the Golden State Freeway which was a constant background hum particularly audible at night.” In another letter to Steir (29 November 1971), Schor writes that she has overcome her doubts, arriving at a sense of worth, confidence and euphoria about her work.

Car Triptych (Part I), 1972, gouache on Arches paper, 30 x 22 inches.

In quintessential Hollywood timing, it is in her final work, at the culmination of this formative period, that Schor has a creative breakthrough. In May 1973, her painting changed abruptly and dramatically, the self-portrait figure in landscape replaced by image fragments and scrawled language. White space opens up in her composition and her gesture becomes more forceful. Romance, May 1973, marked an abrupt pivot with the urgency of someone come to the end of a formative experience. Line is suddenly more jagged, and Schor writes the words “Bruised/ Romance/Kill/Fruit” in an urgent hand, some words smudged or scratched over so as to obscure them. There are areas of dense black contrasting with the white paper, a cloud above a circle from which lines and missiles extend, and lines of red rain down. Nancy Spero’s response to the violence of the Vietnam war in works such as Bomb, 1966, echoes here. Words will remain in Schor’s paintings, and the gap between the verbal and the visual becomes a recurrent theme.

Schor’s young signature is remarkably childlike in these works: just “Mira” followed by a doodle of a bird. One story that runs through the “California Paintings” is youngwoman- goes-forth: a new state, a new school, a new art, a changing world. But recontextualizing the “California Paintings,” and Schor’s then-nascent practice, within the #MeToo movement allows a broader implication than looking back at one artist’s career arc. Amongst her many essays, Schor writes in “Patrilineage” on the exclusion of women artists from art history. Schor never needed rediscovery; she has been well recognized with significant achievements and awards throughout her career. But the politics of the US place women under threat, with many civil liberties won in the 1970s being eroded and others not yet won, making these works resonant again, perhaps all the more so. ❚

“California Paintings: 1971–1973” was exhibited at Lyles & King, New York, from April 12 to May 19, 2019.

After 15 years in London, Kim Dhillon now writes about art from Vancouver Island. She teaches critical theory at the University of Victoria.