Mika Rottenberg

Mika Rottenberg’s eccentric visual narratives use video and sculpture to create relations among seemingly unrelated economies, collapsing space, time and subjectivities. In her exhibition “Bowls Balls Souls Holes” at Sprueth Magers in Berlin, Rottenberg investigates the cyclical nature of luck under the auspices of capitalistic culture. Featuring her signature eccentricity, the exhibition analyzes and reveals the patterns of production and consumption while confusing the boundaries between interior and exterior.

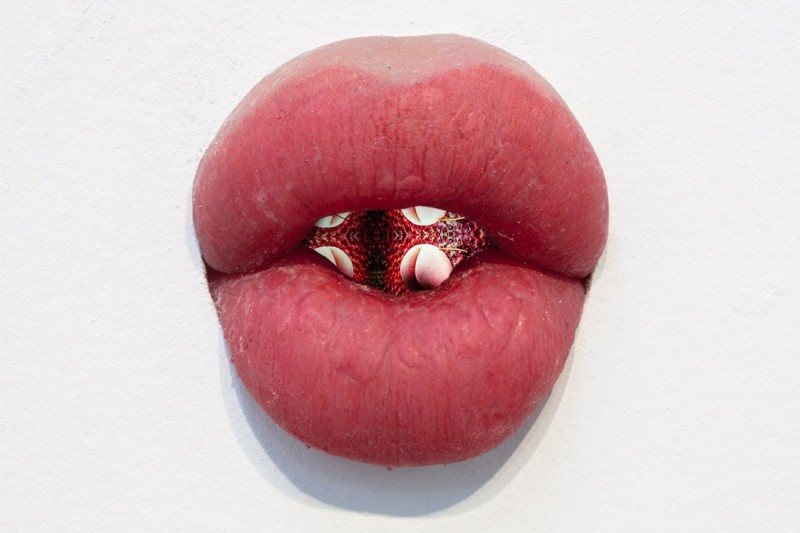

Creating a human body out of the space, a cast silicone mouth, lips parted, pushed its way through a hole in the gallery wall. It was entirely sexy in a sticky, sex store kind of way. I put an eye into the mouth and confronted the first of Rottenberg’s alternate realities. Behind was a small square room of rainbow-coloured, textured walls. Extra-large kaleidoscopic meringues repeated top to bottom and side to side except for where tongues, lips, asses and ponytails emerged. The lips squirted colourful liquids and smoke, ponytails of all colours bobbed furiously as if performing what kind of feverish task, asses condensated and tongues wagged and flicked. The incessant movement was not anxiety-producing as much as it produced a sense of fervour. It was the manifestation of need exemplifying ‘real-life’ cycles of non-stop capital: 7-11, 24 hours, ALL-NITE, keep going, keep going, keep going. Using the slick seduction of the money beast itself, her voyeuristic funhouse of ejaculations suggested the presence of an intake, a place to fuel up. Creating and conflating a myriad of possible insides and outsides, I found myself unsure whether I occupied a space of consumption or production.

Mika Rottenberg, Lips (study #3), 2016, single channel video installation, mixed media, 1:28 seconds. Photo: Tim Ohler. Images courtesy Sprüth Magers, Berlin.

Bowls Balls Souls Holes, her titular video, is set primarily inside a Bingo hall in Harlem that Rottenberg frequented during her research. The video features Bingo hall regulars and a few familiar cast members such as Queen Raqui, a “squasher” and activist, as well as Gary “Stretch” Turner, the Guinness World Record holder for the most clothespins pinned to one’s face. The sequence begins at night with a woman lying in bed in a hotel room (a place to get lucky), looking up at a full moon through a broken corner in the ceiling tiles. The hole allows her to conduct its energy via aluminium foil clothespins clamped on her toes like car jumper cables. Recalling an absurd combination of Ford-ist factory lines, Fischli & Weiss’s The Way Things Go and a Rube Goldberg-esque series of continuous events, she exhales cigarette smoke into the atmosphere, and the moon returns a beam of light into her handheld mirror. She directs its illumination towards an adjacent wall-mounted bubble-gum-foil mandala that harnesses the light, powering a nearby sculptural contraption with a rotating plastic arm that flicks her hair like a wagging tail. Her toes twitch. The water in a bedside fountain boils, bringing bubbles and a cellular-molecular cluster to the surface. They spin like vortices. A solitary light bulb flickers in sync with the hotel neon sign. An AC unit drips. The cycle begins. Considering the theme of luck and Rottenberg’s past work, I could tell that the artist was celebrating an idiosyncratic ceremony in order to critique the way capitalism negates non-monetary generating rituals.

In the following scene, the same woman, now fully fuelled, arrives at the Bingo hall where she works as a game caller to an audience of women, one of whom is Queen Raqui. The camera pans each player’s game cards, dabbers and lucky talismans. It was hard to withstand the melancholy. The Bingo hall, with its unusual real-life characters, was the perfect setting for the piece, but it provokes unavoidable negative associations with gender and socio-economic status. Unlike other scenes in Rottenberg’s work, I was unable to transcend the associated stigmas and relish the empowerment of normally disenfranchised characters. The Bingo caller and Raqui’s undefined psychic relationship helped to transfigure the gloomy scene, if not only to distract from the equally present sense of inequality more than palpable in both their world and mine.

The first Bingo ball gets dropped, triggering the descent of the first clothespin and the commencement of the second cyclical sequence. Floor and ceiling holes coordinate like an astrological planetary alignment, and the clothespin arrives in an indefinite realm below. “Stretch” Turner attaches it to the outer perimeter of his face. Raqui awakes in the hall and employs her psychic third eye-cum-atom-cum-water drop, the hotel sign buzzes and flickers, the AC unit drips, ad infinitum until “Stretch” Turner creates a complete plastic, facial “mandala.” These activities form a cosmos where each character exists because of efficient, dependent interrelations.

Mika Rottenberg, installation view, “Bowls Balls Souls Holes,” 2018, Sprüth Magers, Berlin. Photo: Tim Ohler. Courtesy Sprüth Magers, Berlin.

In this video, Rottenberg uniquely illustrates the materialization, consumption, depletion and restoration of energy (luck) outside of corporate, patriarchal or other conventional monetary systems. Her world consists of spiritual, physical, mechanical, psychic, electric and nuclear energy as manifested through human will. As a result of her propensity to employ the bizarre, rendering normal daily functions equally illogical and thus potentially meaningless, this work questions and refutes capitalistic hierarchies that establish the ultimate goal of life as the generation of money. (And, money as the sole source of luck.) Instead, her work consistently challenges us to revalue our own unique aptitudes, including the energy of our bodies and gender, and create more self-sufficient luck.

Shown on the High Line in NYC in 2016, the associated press release for the video quotes the artist as saying, “It’s magic—finding little solutions for things that were not necessarily a problem.” This is humble. Rottenberg’s imaginative and shockingly comparable realities symbolically solve much bigger real-life problems. Rottenberg creates and then dissects her—and, by extension, our—world, layer by layer, topographically revealing eccentric, fascinating and yet problematic structures. By featuring marginal subjectivities, using humour and absurdity, she reveals rather than hides its simultaneously vulnerable core, resulting in artwork that has the potential to be replenishing. She creates alternative worlds that are transformative because they are deeply felt. We could be so lucky as to one day inhabit one.

“Bowls Balls Souls Holes” was exhibited at Sprueth Magers, Berlin, from September 29 to November 10, 2018.

Jasmine Reimer is an artist and writer living and working in Berlin and Toronto. She studied at the University of Guelph and Emily Carr University.