Mickalene Thomas

Beyond its considerable aesthetic and cultural value, “Mickalene Thomas: Femmes Noires” signified an important moment for the Art Gallery of Ontario (AGO). Responding, if belatedly, to demands to decolonize and feminize the art institution, the AGO gave up its entire fifth floor to a queer Black woman artist.

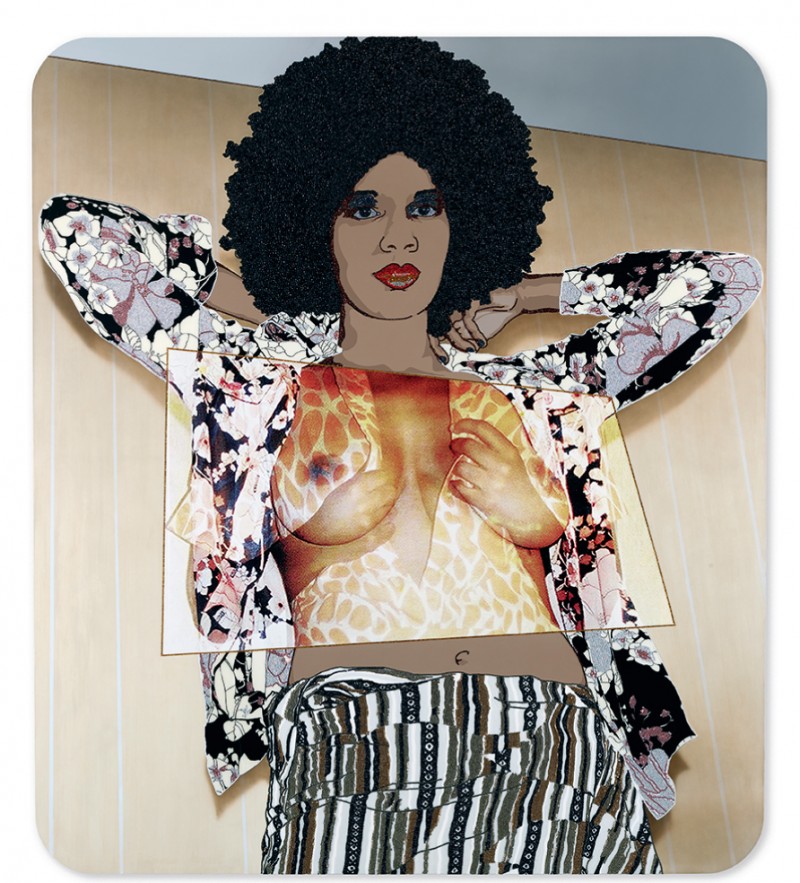

Mickalene Thomas is known for her large photographic portraits of African-American women. Posed and poised, seated or reclining, her subjects appear beautiful and confident within domestic spaces that vibrate with colour and pattern. Here, the genre, subject and style—decorative portraits of Black women—remain but spiral out into the diverse media and materials of video, silkscreen, installation, reflective mirror, oil and acrylic paint, enamel, rhinestones, fabric and furniture. The assemblage process of gathering and reconstructing nascent in Thomas’s photographs and as seen in her arrangements of fabrics and props has evolved into a central organizing principle and figure that runs through all the works shown here. Collage neatly expresses Thomas’s intersecting interests in representations of Black women and modernist art history.

Mickalene Thomas, Portrait of Maya #10, 2017, rhinestones, silkscreen and acrylic on canvas mounted on wood panel, 96 x 84 inches. Private collection, Toronto.

This collage impulse, and its Cubist incarnation in paint, was valued by avant-garde artists for its challenge to the existing order of realist representation and for its ability to express the increasingly fragmented experience of modern life. It’s not surprising, then, that African diasporic artists, with their existential dislocation— described by Thomas as “doubleconsciousness”— might also be drawn to that approach. Thomas’s work fits into a recognizable lineage that includes Romare Beardon, William Johnson and Wangechi Mutu. And, in what might seem an unlikely alliance, Thomas also looks back to White male modern painters, such as Édouard Manet, for example, for his resistance to the social and aesthetic status quo but also because, as Thomas pointed out during an exhibition tour, many of those artists painted Black women models. Departing from the standard mode of representing such models as either servile or exotic, those more respectful portraits were not included in the Western art canon.

Form and content—revolutionary collage and the visual presence of Black women—align here. Thomas’s goal is to correct that omission by representing those who, despite great obstacles, made contributions to Black culture, and, in so doing, provide models for future Black artists. Thomas’s work celebrates the beauty, talent and sexuality of friends, lovers, family and a pantheon of literary and popular culture figures—her “Muses, mothers and celebrities.” But beneath this bravura lie an almost palpable pain and sadness—the historic weight of exclusion.

Most successful and exciting were eight variously sized, large, painted wood panels, their female subjects— appearing as majestic goddesses in their beauty and command— centrally composed within a riot of shapes, colours and patterns. Their photographic origins are all but obliterated by juxtaposed shards and shades of flat paint in fresh and surprising colours, painted surfaces mimicking faux wood panelling, animal skins and leatherette, a riot of jiving painted fabric patterns, bits of photo-silkscreen imagery and textures made from rhinestones and poured and patterned enamel. It’s an aesthetic foraged and forged from Thomas’s memories of 1970s design and the patterned backgrounds in noted Mali photographer Seydou Keïta’s West African photographic portraits.

Diahann Carroll #2, 2018, silkscreen ink on acrylic on mirror mounted on wood panel, 182.9 x 152.4 x 5.1 centimetres. © Mickalene Thomas/SOCAN (2018). Image courtesy of the artist and Galerie Nathalie Obadia, Paris/Brussels.

Thomas’s skilled and joyful use of materials is apparent in the rhinestones that fill out solid areas, such as the Afros that halo her subjects’ faces and form shadow lines. Like the modernists, she eschews realist pictorial space in favour of formal features of colour and form. Through considerable compositional accomplishment, Thomas corrals this collision of disparate fragments into a coherent dazzle of visual pleasure. One of the most effective of these is the reclining nude composition Shinique: Now I Know, 2015.

The remaining works, though important for developing Thomas’s concerns, seem like formal experiments. Similarly structured through collage, four video works combine found and original audiovideo material. Two pay tribute to Black women who achieved pop culture celebrity within the realms of song, dance, comedy, film and literature, and opened paths for younger Black artists, including Thomas herself.

It is video’s more expressive sound component that evokes the sadness underlying these tributes. In the eight-channel Los Angelitos Negros, 2016, Eartha Kitt, with tears streaming, sings a moving lament about the absence of Black angels in Western iconography. Three identically dressed and coiffed models, lip-synching in pantomime, share in solidarity that painful history.

The wall-size two-channel video Do I Look Like a Lady? (Comedians and Singers), 2016, assembles a history of Black women in the entertainment world: the disarming and energetic Josephine Baker, beautiful and soulful Whitney Houston and the formidable and assertive Nina Simone.

Two other video works are more personal. The black and white four-screen projection je t’aime deux, 2014, mixes intimate and erotic scenes showing the artist and her lover. Thomas’s attempt to offer positive representations of queer female sexuality relies on conventional clichés—extended shots of crossed legs, stilettos and an arched back and lingerie-laced behind provoking uneasy questions about the gendered gaze. Are voyeuristic looking and stereotypical representations of sexuality benign, and only problematic within unequal power relations?

Three large, warm-toned Polaroids appeared as 19th-century photographic processes, their curved gold frames suggesting daguerreotypes. Two portraits replicated JT Zealy’s ethnographic studies, their naked Black subjects looking directly out from their frames. In a third, a reclining nude presents earlier pornography, eroticizing Black female sexuality. Where other artists such as Carrie Mae Weems incorporated these images into hard critiques, Thomas’s works were subtly distinguished from their offensive originals by softer expressions and patterned backgrounds, making them uncomfortable to look at. Their titles—Courbet 4 (Marie: Centered), Courbet 2 (Melody: Centered) and Courbet #5 (Marie: Relaxing), 2011— reference the artist whose erotic and explicit images have, like positive images of Black women, been buried by art history. Rather than rejecting that White male tradition, Thomas, in her adamant exposure of queer Black women’s sexuality, affirms and revises them.

“Femmes Noires” contributes to the presence of Black women in art, as both artists and subjects. Though an important step, the goal of diversity can be realized only by extending that principle into the museum’s more structural realms, such as its boards, directors, curatorial departments and collecting strategies.

“Mickalene Thomas: Femmes Noires” was exhibited at the Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, from November 29, 2018, to March 24, 2019.

Jill Glessing teaches art history at Ryerson and York universities, and writes on contemporary art and culture.