Michael Williams

An attractively clever species of white noise emanates from the canvases and accompanying works on paper in “Yard Salsa,” Michael Williams’s solo exhibition at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, his first one-person show in Canada. Does It Hurt to Be Crazy, a 2014 piece that was also shown at MoMA’s “Forever Now: Contemporary Painting in an Atemporal World,” appears to answer its own question in the negative, though perhaps after some kind of an internal struggle. The painting is a highly charged yet oddly, even dreamily calm semi-apocalyptic image of Americana. It involves layer upon pictorially collaged layer of imagery and juxtaposed techniques, in which atmospheric space and picture plane appear to have fought each other to a draw. A palette of hot acids and cooler, faded newspaper tones augment the visual onslaught in which a pink, cartoonish mascot of an ice cream salesman stands in front of the stars and stripes on a flagpole, his arm raised in welcome. Flanking him is a giant floating yin yang symbol, while some kind of tripped-out, painterly stick figure leapfrogs over the lot, in front of a sort of dystopian suburban backdrop, complete with parking lot and sleepy-looking bedroom community houses. Other weird things are also going on amid a loud formal din, and the total effect, other than sound and fury, is to achieve some kind of social commentary by defeating the coherent possibility of it. It appears somehow to be quietly saying that in this day and age it can hurt not to be crazy, especially if you’re a painting.

Michael Williams, Mauve Dog, 2014, inkjet, airbrush and oil on canvas. Private collection. All images courtesy Montreal Museum of Fine Arts.

There is a strong feeling of raucously enjoyable cacophony in Williams’s paintings, augmenting and criss-crossing the exhibit, as well as moving from side to side along the walls, allowing the eye to randomly scan the nearly 50 works on paper hung in two major groupings. While a straightforwardly diachronic or sensical narrative is never forthcoming despite the iconic, cartoonish figuration and comic book textual flow, there is the achieved sense of a coherent, humorous and humane stance emanating from the installation on view. Though the works are drawn from different series of Williams’s production over the last several years, the show balances on the right side of the line between revealed kinetic energy and its dissipation. This works out, in part, because Williams begins each painting by slow labour on the computer, working an image in Photoshop until it is expertly printed onto canvas. He often accentuates that with freely but finely applied airbrushing. Only then, in the case of many of the works but not all, does he reach for paint and brushes, creating a complex formal web of painterly activity.

Honest, spontaneous laughs can result from our first impression of many of these works, and the way this artist deals with the critical baggage surrounding expressive painting is both funny and engaging in its aesthetically responsible species of humour. One of his more economical compositions is the (unresembling) self-portrait Morning ZOO from 2014. We see a bald neo-expressionist (complete with plumber’s butt and love handles) from behind, brush in hand, making a painting-within-a-painting that we clearly understand has been deemed to be pretentious, in a too clean studio environment. The entire large canvas is ink-jet printed with no handmade marks on it whatsoever, thus absenting the autographic mark from its representation. This kind of cheekily smart conceptual play is not immediately obvious, but with time some relationship to ideas about the complexities and responsibilities of representation emerge from the wild grotesquery, the faux danger and the punning titles (i.e., Ikea Be Here Now).

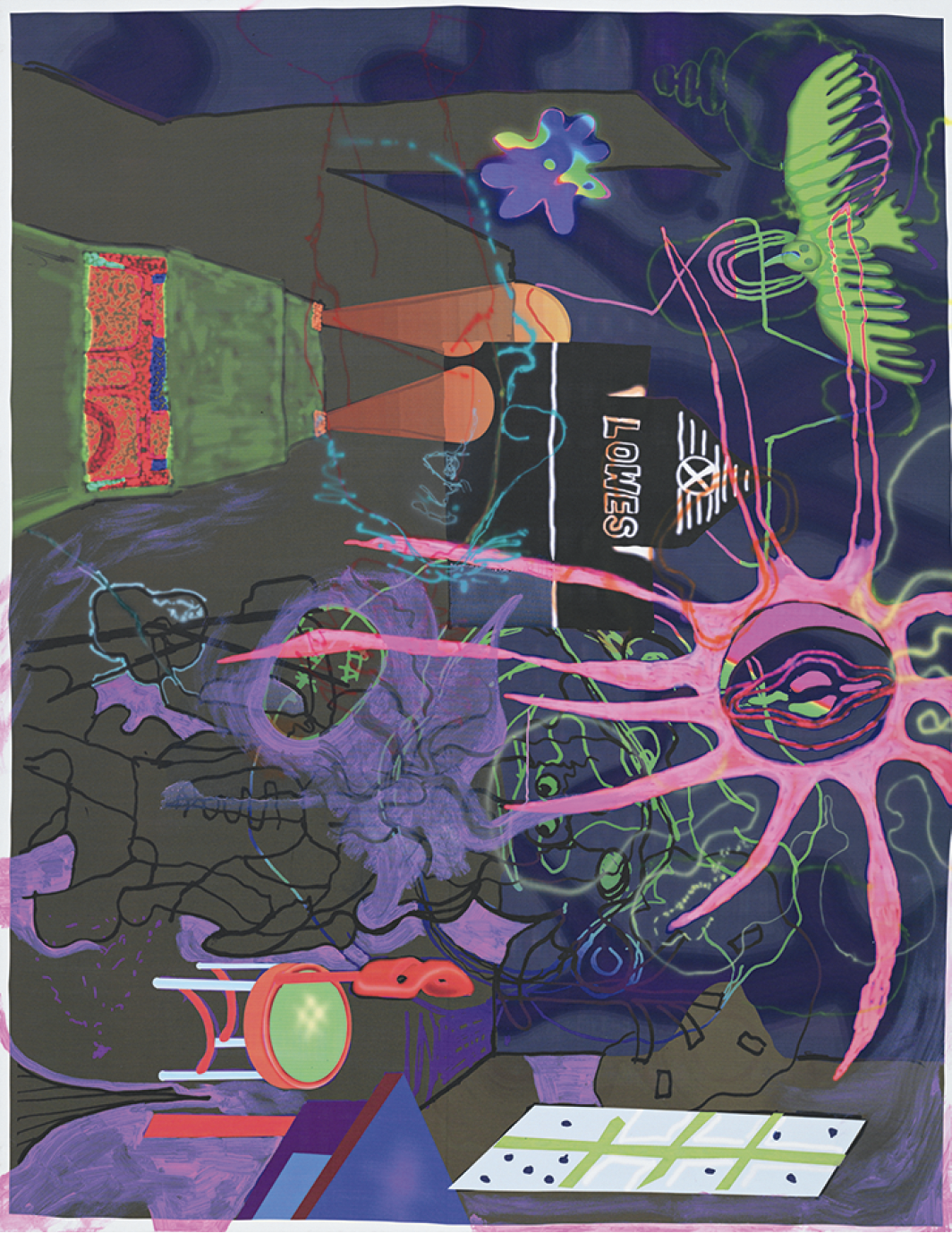

Michael Williams, Pygmy Twylyte, 2014, inkjet, airbrush and oil on canvas. Collection of Tim Walsh and Mike Healy, Santa Barbara, California.

All of which tends to refocus the viewers’ attention on the pleasurable formal spectacle unfolded before us each time a fragment of imagery or seemingly coherent storyline begins to maintain its shape. We can see that there are themes of interest and consideration at work here, but as we try to assign a linear structure to the way concepts might be intended to rank themselves into file, the clear invitation the works offer to just look at their visual music, rather than try to make out a verbally coherent meaning structure comes back. It seduces us away from assigning a too easily defensible statement of purpose to the goings on. The title of the show (and the piece it’s named after), “Yard Salsa,” seems to turn into an encouraging metaphor for how to best decipher and enjoy Williams’s production, in that his goopy mixture of distinct but blurred, recombined spatial and figural elements somewhat reveals and then coyly obscures any finalized knowledge of how to feel or what to say. The gorgeous 2014 canvas Mauve Dog is a case in point, where waves of beautiful activity jar against the quickly created expectation that we ought to be able to pin down what’s what and where we are going. But we can’t.

Many artists seem present in the matrix of this work, from Jean Dubuffet to Sigmar Polke, Philip Guston to Jean-Michel Basquiat—Williams manifests artistic family relationships that feel well assimilated and accommodated. The intellectual aggression of an artist like Albert Oehlen, and the theoretically charged pictorial ambitions of older contemporaries like Laura Owens, Fiona Rae and Daniel Richter all come to mind looking at Williams—to be politely waved aside by a tripped-out, spiritually confident posture, that seems equally resolved if we decide to just accept as brainy culture jamming the medium messaging that is clearly going on here. Perhaps Williams’s formalism and conceptualism have blurred into one another to the degree that they have salsa-fied, and the best thing we can do is just hang out with the paintings and kick back in his mental backyard. The victory Williams’s work achieves is that the ironies that result from these seemingly contradictory, potentially cynical confrontations all appear to be comfortably living together and making their own sounds, mostly harmonizing but also making music in the disharmonies too. ❚

“Michael Williams: Yard Salsa” is on exhibition from June 9 to September 27 at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts.

Benjamin Klein is a Montreal-based artist, writer and independent curator.