Michael Semak

Three children in rain boots and dark slickers blow bubbles in an autumnal park. There are joy and excitement in their faces as their small bodies reach for a tiny soap bubble, finely delineated against the deep, black tones of the wooded background. In the distance, a clearing is visible through the trees. The sweetness of the image combined with its chthonic overtones typifies Michael Semak’s photographs of the 1960s and ’70s. Curator Andrea Kunard recently culled 125 images from this period for a travelling Canadian Museum of Contemporary Photography exhibition. The gelatin silver prints, with their deep blacks and ranges of greys and whites, portray people in various situations and interactions. Many allude to universal themes: death, sorrow, loneliness, life itself. Like Edward Steichen’s hugely influential 1950s exhibition “The Family of Man,” Semak shows the commonality of human experiences and emotions in diverse situations, cultures and geographies.

Semak’s images respond to a human yearning for empathetic understanding, a yearning that can be accommodated only by those pictures of others that provoke a sense that we belong to a common species. Paradoxically, Semak let this commonality shine through a sense of otherness, which he emphasized through dramatic viewpoints, strong contrasts and, at times, his choice of subject matter: people who live on the margins of society. The uncanny sense of simultaneous otherness and commonality that these methods provoke is deepened by time.

Michael Semak, Street Scene, Moscow, Russia, USSR, 1975, gelatin silver print, 19.6 x 16.4 cm. All photographs courtesy Canadian Museum of Contemporary Photography, Ottawa.

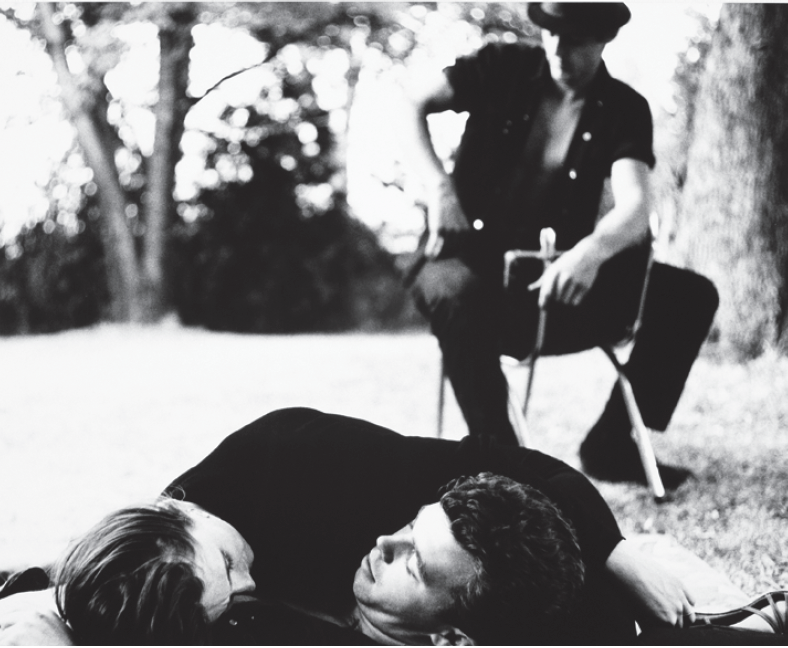

The sense of estrangement in these pictures heightens the awareness of this commonality; intensely human emotions are recognized in people and situations even so distanced from us. Semak was drawn to subjects outside the mainstream, such as people in isolated, dysfunctional communities, patients in mental hospitals and members of the Black Diamond Riders motorcycle gang. In 1966, he took a series of photographs in Warrendale, an institute for emotionally disturbed children. In the untitled photographs, the youths’ body language speaks of distress and dejection. The children appear lost in a world of their own—even when they look at the photographer, all we see is their mistrusting eyes and secret suffering. The consoling hands of councillors, which become prominent in some of these images, seem as hopelessly ineffectual as Semak’s own loving hand reaching out towards his cancer-stricken wife in a deeply personal image of 1973.

In Semak’s photographs, specifics of time and place—names, dates, historical context of events—are subsumed to serve a metaphorical function. In 1975, travelling through the USSR, he began to compose his images more deliberately in order to transcend their particularity. We find little in the images of that journey that would give us information of what it would be like to live in an oppressive communist state; absent are the queues for consumer goods, crowded apartments or ubiquitous monuments familiar from the newsreels and press photographs of that time. Instead, Semak shows us workers on a break, children drawing on the pavement, a woman strolling in a quiet park, or a scene at the art gallery, all situations that could have been shot anywhere in Europe or North America.

Michael Semak, Untitled, 1966, gelatin silver print, 17.9 x 25.2 cm.

To be sure, some details identify locations, but they are not emphasized. In the art gallery photo, for instance, the traditional headdress of a woman and, perhaps, the painting of a battle-ready soldier place this picture in eastern Europe. But the landscapes and the scene of a proud father taking a picture of his daughter in front of a statue could have been shot in many other galleries of the world. In this picture, Semak carefully orchestrated gestures and placements to turn the image into a meditation on masculinity: the painted soldier’s posture matches exactly the posture of the man in the foreground, who is not holding a rifle but a camera aimed at the little girl. The light, the camera, the man’s attention, everything is focussed on the girl, who is posed in front of a sculpture of a male figure. The older woman sitting on the side looks weary, her glance at the father distrusting, skeptical, as if knowing that this benign side of masculinity could turn at any moment.

In addition to the artistic merit of this exhibition, the work also documents a fascinating in-between stage in the history of photography, between the straightforward “truth” of Modernist photography and the emphatic artificiality of its postmodern critics. Semak’s early work owes much to the American photographer Robert Frank’s edgy, documentary style, which influenced a new generation of American photographers (Garry Winogrand and Lee Friedlander among them). Frank employed unusual viewpoints and lighting and incorporated “mistakes” rather than hiding them. In Canada, documentary photography that freely included expressive, subjective points of view emerged in the sixties, not in the least due to its promotion by Lorraine Monk, the then executive producer of the National Film Board’s Still Division. Semak was one of a number of photographers who were sent out by Monk to photograph events and everyday life in Canada. The assignments were loosely structured to fit broad projects with titles such as The People of Canada. The choice of subject matter was left, more or less, to the photographer.

Michael Semak, Club House of the Black Diamond Riders, Toronto, Ontario, 1966, gelatin silver print.

The exhibition shows Semak’s development from a more “objective” stance to deliberate control of situations, in order to express preconceived ideas. But all the photographs retain a claim to veracity; they provide the illusion that the photographer just happened by. It is this kind of modernist illusionism against which a younger generation of art photographers rebelled. Artists such as Evergon, Donigan Cumming and Diana Thorneycroft, to name but a few photographers who are indebted to the expressive, subjective work of Semak and others, never leave a doubt about the constructed reality of their photographs.

Postmodern photography teaches us that what is posited as a universal view is always influenced by the subjective ideas of the photographer. We have learned that a desire for commonality, for wholeness, can result in an illusionary truth that negates differences and effectively silences idiosyncratic voices. But what we have not learned is to forget our desire to belong, our impulse to recognize experiences and emotions we all share. In a postmodern culture with its insistence on differences, Semak’s photographs, with their unabashed longing for a universal humanness, create the shock of the old. ■

“Michael Semak,” Canadian Museum of Contemporary Photography, Ottawa, May 7 to November 13, 2005 (Circulating).

Petra Halkes is an artist and writer living in Ottawa. Her book, Aspiring to the Landscape, On Painting and the Subject of Nature, has just been published by the University of Toronto Press.