Michael Harrington

Michael Harrington paints members of the human species in their natural habitats. In the past, he has painted them congregating in parking lots and city streets, at barbecues and doggy parks as well as in the confines of their domestic spaces. In his latest exhibition in Ottawa he focussed on the behaviour of the male of the species in the cozy upholstered environments of corporate businesses. The completely artificial settings of his paintings, in which everything appears to be designed for and by humans, comes across as the natural environment of these creatures. It is, indeed, a human-centred world; even nature, whether in the guise of ominous skies, scenic wallpaper or stilted floral bouquets, appears to exist only to provide the right background or the right props for human activities.

Most of the paintings in the recent show allow you to imagine yourself looking in from behind a one-way mirror in a fourth wall. A simple one-point perspective, a discreet distance from the figures and an unimpeded foreground are frequent features in these works. The single figures and groups that populate his canvasses remain completely oblivious to the viewer. Even when some businessmen pose for a group portrait in their hotel lobby (White Jackets), they face an invisible camera somewhere off slightly to the side. They are engaged in a ritual that doesn’t include us but is instantly recognizable. Amid the clutter of haphazardly placed chairs, patterned wallpaper and carpeting, they raise a glass or grin at the camera. We can almost hear them: “Harry, a little more to the left. Dave, put your arm around Bill’s shoulder.”

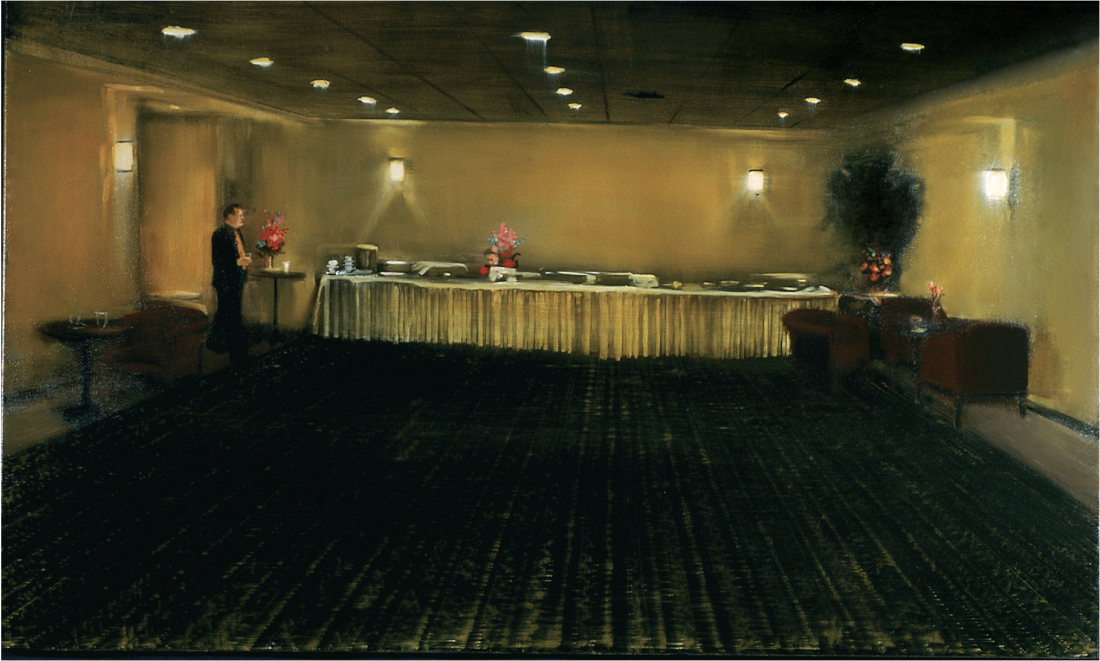

Michael Harrington, Banquet, 2005, oil on canvas, 36 x 60”. All photographs courtesy the artist.

Harrington portrays his people with sensitivity. He paints a man’s world, but these businessmen, in their suits, borrowing dignity and power from the corporate architecture they inhabit, are about as powerful as peacocks. It is a bit surprising that this is the work of a male artist; few of Harrington’s gender would be willing to reveal masculine vulnerability with an empathy that could only have been derived from self-understanding. Harrington’s men may make us smile but they never become caricatures, and his personal investment allows us to recognize ourselves before we laugh.

The corporate habitat, as we learn from Harrington’s studies, acquires an appearance of authority and security through meticulously designed architectural environments. In Banquet, 2005, a long, skirted table appears like a lighted stage at the far side of a salon. Covered dishes await the guests, who might still be at a conference in another room. A man enters, possibly checking the preparations, but everything seems as orderly as the one-point perspective of the painting. The glowing colours—gold, greens and red—add a classic touch and connect us to traditions of royalty and oil paintings. There are soothing, ambient lights, soft, comfy chairs and a touch of nature in the form of a potted plant and the ubiquitous bouquets. To call this room “womb-like” may be putting too fine a Freudian point to it, but everything appears designed to make the men feel at ease and become seamlessly absorbed into a corporate environment that will lend their appearance a certain authority.

Not only the stage but all other essentials of corporate theatre get full attention in Harrington’s paintings: the shield of anonymity that is created by the dress code of suit and tie, the avoidance of surprises through expected rituals such as round-table conferencing, lounge schmoozing and cocktail drinking, and the self-assured postures of the men.

Michael Harrington, Red Blinds and Socks, 2005, oil on canvas, 8 x 10”.

Harrington conjures up these corporate spectacles just as sure-handedly as he deconstructs them. What is so fascinating about these luminous small and mid-sized works is the subtle and not so subtle ways in which he lets the men’s insecurities leak out. Despite the carefully constructed environments, rituals, dress codes, gestures and postures, a pervading sense of both ease and unease hangs in the balance.

The artist accomplishes this through several strategies. First, there is his play with composition, light and shadow. This, as the Baroque artists of the past knew, can completely destabilize a space. In Banquet, for instance, the table, tilted ever so slightly, seems to attempt an escape by floating away on its own shadow; the stability, expected to be delivered by the accentuated perspective and the classical colours of the painting, is thoroughly subverted. The corporate spectacle is further undermined by Harrington’s choice of hotels and meeting rooms that are somewhat second-class; not shabby exactly, just a touch old-fashioned but still perfectly serviceable for middle-management conferences. The outdated architecture reveals a corporate image that is not as timeless and untarnished as it would like to portray The bodies of the men reflect the aging process of the buildings in which they move; Harrington paints a bulging tummy for one, a bald patch or sagging shoulder for another. A source of anxiety, no doubt, for the men who seem as much in need of renovation as the rooms in which they find themselves.

Michael Harrington, White Jackets, 2005, oil on canvas, 10 x 12”.

Less subtle but rather hilarious is Harrington’s sabotage of the suit-and-tie uniform by additions of brightly coloured patterned ties, red socks or even, inexplicably, a man in his undershirt. These strange anomalies also interfere with the expected narrative. Although the paintings suggest specific plots, there are never enough clues to determine the whole story Like stills from unknown movies, they remain wide open to interpretation. The offhand titles, such as Red Blinds and Socks, Meeting Between Arrangements or Figure Drinking Milk, seem designed to keep it that way.

If the demands of the men’s embodied existence intrude in the perfect corporate image, the reverse is also true. Private moments, such as the one a man in Autumn Suite appears to enjoy, can be colonized by corporate demands. Having shed his suit for a T-shirt and a can of beer, the man stares into space, as if unable to take command of his own body. Taken from an unusual point of view (for this series), a corner of the bed disappears in shadows. The man seems uncomfortably hemmed in between a mysterious space in front of him and the door behind. On both sides he is confronted with notices: a paper posted on the door, another sheet (a memo?) on the bed. Even here, in this private space, corporate directives are inescapable.

Harrington’s paintings show a keen sense of exactly those moments in which private and public lives infect one another and the comfort levels of both zones are disturbed. ■

Michael Harrington exhibited at Galerie St-Laurent+Hill in Ottawa from April 15 to April 27, 2005.

Petra Halkes is an artist and writer living in Ottawa. This fall, her first book, Aspiring to the Landscape, On Painting and the Subject of Nature, will be published by the University of Toronto Press.