Michael Dumontier

Years before the artist Michael Dumontier graduated from art school, I was standing in an exhibition hall of the National Gallery of Canada. At the far end, exuding power and majesty was the painting Voice of Fire, Barnett Newman’s monumental statement of abstract expressionism. Two metres to the left, dwarfed by the five and a half-metre painting, was an elderly man reading the work’s tombstone description on the wall. And two metres to his left, at the same level as the tombstone and projecting perhaps five centimetres from the wall’s surface, was what appeared to be a white box, roughly 15 centimetres by 10. The man studied the “tombstone,” then moved left and carefully examined the box: front, top, sides, then back to the tombstone, then the box again. He repeated the ritual several times. Then he shook his head, smiled and left. I walked to the box and examined it. It was a thermostat.

Move forward to another time, another place, another gallery, another show; I make my first acquaintance with a Dumontier work. Surrounded by larger and more dramatically wrought companions, it distinguishes itself through modesty and elegance. I’m not sure why, but I found myself recalling the man, Voice of Fire and the thermostat.

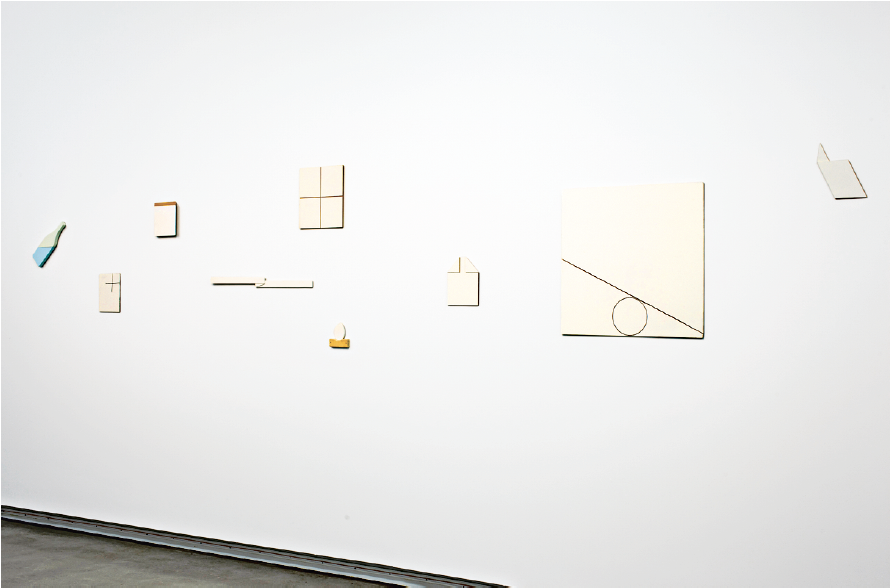

Installation view of Michael Dumontier’s “A Moon or a Button,” 2012. Photographs: William Eakin. Images courtesy the Plug In Institute of Contemporary Art, Winnipeg.

And now comes “A Moon or a Button,” Michael Dumontier’s first solo show in a public venue. It is one of two Micah Lexier-curated exhibitions simultaneously displayed at Winnipeg’s Plug In ICA. The second show, entitled “Like Minded,” brought together 36 artists whose work, in Lexier’s opinion, reflects interests and approaches similar to Dumontier’s. Several are senior and distinguished: Michael Snow and Arnaud Maggs, for example, as well as others less familiar. While diverse and interesting, given the juxtaposition and with only one example of each artist’s work, the impression is very much that this show’s primary role is to catalyze response to the conceptual cohesion of Dumontier’s exhibition in the adjoining space. Here, Lexier has made a thoughtful selection of 26 pieces by Michael Dumontier, a number sufficient to enable an installation that, in its precision, closely matches that of the works themselves. Wisely, he has chosen to include nothing produced prior to 2009, so while one or two pieces may be familiar, to all but those with access to Dumontier’s studio, most will be new.

The placement and spacing of the 25 pieces in the gallery—the 26th appears separately in an outside window—have been fastidiously calculated to modulate and shape audience experience. Individually and collectively, these pieces evoke a spirit of democratic generosity that finds expression both in subject matter and in the consistent spareness of presentation. Stripped to their formal essentials are representations of socks, a tree, sticks, envelopes, bottles and boxes, books, a magnet, needles, thread and paper. All the pieces are relatively small, their scale in general matching that of the fixed accoutrements of the gallery itself. Commonness and equitability are further accentuated by the pieces being either untitled or having titles that are bare-bones description. The exception—and exceptional too in being the only electronic work in the show—is cryptically titled This way, that way and features a randomly rotating arrow.

Michael Dumontier, This Way, That Way, 2009, mixed media, 9 x 7 x 44”.

Imagine being in a silent room, and out of that silence, suddenly, there is a single, pure, perfectly pitched note. That is the quality of every one of Dumontier’s pieces, and a quality too that greatly limits any attempt to talk about them individually; this particular D-flat minor, for instance, being rather anxious or that C major somewhat innocent and naïve. Rather, there is greater profit in thinking of the show as a whole, of experiencing it in the same way as one would, say, the larghetto from Mozart’s final piano concerto, in which every measured note puts one in anticipation of a next, which we’re sure we’ll know but which, when it does come, is always, in the most discrete way, slightly contrary to expectation and yet which, upon reflection, is also inevitable. While similarly delightful, the fearsome cleverness of Dumontier’s work lies not just in its own unique expression of this kind of spare, rigorously concerted elegance but, again like music, in its capacity to infiltrate this affect throughout the entire, perceptive envelope of its containment.

This is brilliantly exploited in the current show, the installation of which so fully implicates the whole exhibition space that one should be more congratulated than forgiven for failing to recognize where art begins and ends. Seldom have the qualities of the traditional white cube been so masterfully employed. The plainness of Dumontier’s subjects and their stripped-to-the-essentials rendition is fully complemented by a meticulously calculated installation that focuses, almost pathologically, upon giving everything equal emphasis. Similarly, the cool, fluorescent lighting is reduced and restrained to a degree of almost, but not quite, complete neutrality; a strategy that bathes all in a chromatic flatness barely relieved by the intrusion of a few discretely placed and severely dimmed tungsten floodlights. While perhaps not quite as radical in its effect upon the eye as was 4’33”, John Cage’s notoriously silent, three-movement musical work, upon the ear, this show succeeds in stimulating a similar response: prime a sense, deprive it of expectation and wait for it to fill the void, and when it does, watch as the audience or, in this case, viewer, finds the boundaries between art and not art become increasingly difficult to discern. Does this bench upon which I sit while thinking about Dumontier’s Untitled (black sock) on the floor merit more or less attention? What about the security camera on its wand suspended from the ceiling or, well, that thermostat on the wall just to the right of Untitled (needle and thread)?

Installation view of “Like Minded,” 2012, Plug In Institute of Contemporary Art, Winnipeg. Photograph: William Eakin.

I like to think that chap in the National Gallery who devoted so much attention to that other thermostat found himself, like me, thinking about the response small children have to experience. It is this that Dumontier reiterates so well. No matter how banal, small or seeming slight, to a child everything is wondrous and new. Did that viewer in the National Gallery then extend his understanding to include singularity, transience and absolute irretrievability and, like me, find himself reminded that all experience remains deeply important and worthy of full attention all the time? Did he then think that it might well serve him to retrieve that sense of wonder? Perhaps so, for when he left the gallery he did what I did when I left Dumontier’s show; he smiled. ❚

“A Moon or a Button” and “Like Minded” were exhibited at the Plug In Institute of Contemporary Art, Winnipeg, from January 28 to March 25, 2012.

Richard Holden is a photographer who lives in Winnipeg.