Messages from Max

Maxwell Bates was one of Calgary’s first Modernists and, in his day, a well-known Canadian artist. In Maxwell Bates, Biography of an Artist, Kathleen Snow and the University of Calgary Press have produced a worthwhile, though by no means perfect, book. For the most part it is a straightforward account of Bates’s activities, including exhibitions, with some attention paid to his paintings and graphic work. Snow’s discussion of the art quotes heavily from other writers who have considered Bates’s work “critically” on the assumption (also embraced by the author) that he not only was but remains, an important artist. She uses Bates’s own recollections, philosophical musings, flirtation with mysticism and poetry to further our understanding of the man, his life and work. Though I thought the inclusion of Bates’s poems—usually written in the time frame under discussion—the most unusual aspect of this book, I liked them. Like friendly footnotes, they offered unexpected insights; they were messages from Max.

Kathleen M. Snow, is a former librarian and currently Associate Professor Emeritus of the Faculty of Education at the University of Calgary. She has had a long interest in art and knew Bates for many years, although not well enough to grasp “the elusive essential of this complicated man.” She goes on to observe: “His protective walls were strong and I am conscious that in this account I have not been able to penetrate him.”

What she has been able to work through, however, is a wealth of information, both by and about the artist. There is much to recommend in this biography: insights into the early history of Canadian Modernism and a bibliography that lists important sources, including Bates’s own writings. Her chapters on the London years (1931-1940) and on his return to Calgary in 1946 are particularly welcome; the story of his period as a prisoner of war is gripping; and there are interesting details on his growing recognition as an important, though not always well-received, Canadian artist.

Professor Snow is obviously sympathetic towards this variously difficult, insensitive, disturbed and utterly charming man. The admirable humility she displays in admitting she may not be up to the task of fully “penetrating” his personality is what makes me wary of the dust-jacket claim that “this biography will become the standard reference on this reticent, driven artist, who is best known for his evocative, sometimes haunting, depictions of the human figure.”

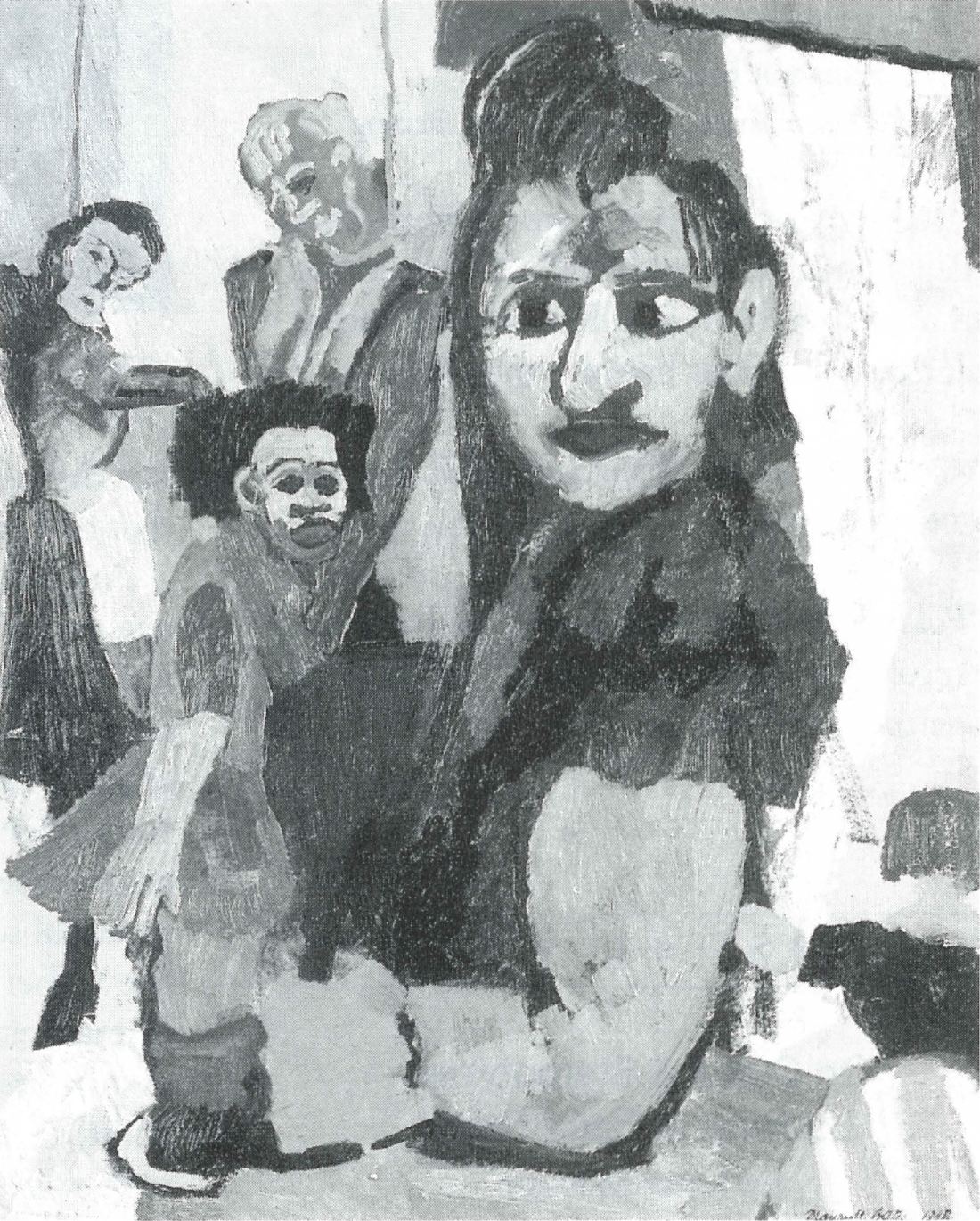

Maxwell Bates, Puppet Woman, 1948, oil on board, 50.7 x 40.7 cm. Photograph: John Dean.

The assessment is somewhat misleading. Maxwell Bates: Biography of an Artist is short on analysis and its visual gaps diminish our ability to get close to the artist and his time. There is also a glaring blunder in chronology: a work dated 1927 in the colour section is discussed as a work done after his trip to Chicago which apparently took place in 1929. But more troubling is Professor Snow’s uncritical advocacy of her subject. Her first chapter is marred because she treats the Calgary art scene only from his perspective. As a result Alfred Leighton (the British painter who viewed Bates as an upstart Modernist) is cast as the bad guy rather than a disputant in a significant cultural debate. In another chapter Snow quotes Bates referring to criticism of his work in the Letters to the Editor section of a Calgary newspaper. It would have been useful to find these letters as independent confirmation of both attitudes towards art in Calgary, as well as of Bates’s memory. Nor are illustrations of work by other artists who were part of Bates’s milieu included. While most of us can conjure up a Matisse or a Gauguin, few will be able to imagine a work by Lars Haukaness, an early teacher, or pieces by Anthony Tyrrell-Jones, William Leroy Stevenson, Jock MacDonald, Illingworth Kerr or even Leighton himself. It is especially irritating to read about Bates’s rejected mural designs for the City Airport and have the author conclude, “By contrast, the work approved by the city seemed sentimental.” Neither of them are reproduced.

It seems clear that Bates was very much of his time, if not his place. He settled into a middle-of-the-road Modernism, the popular “compromise” of many North American artists who were solidly engaged with post-Post-Impressionist idioms. In 1947, when he exhibited his work at the Vancouver Art Gallery, a local critic wrote: “He’s all right, this Bates. He paints good stuff. Folks in places like New York would go crazy about him.”

In fact, Bates’s work conjures up so many pre-1940 American and Canadian artists that it becomes something of a game to decide which artist he comes closest to: Yasuo Kuniyoshi, Walt Kuhn, Ben Shahn, maybe, Marsden Hartley, sometimes, the Soyer brothers, yes, especially their early work, Abraham Walkowitz, yes, Max Weber, like Bates a Henri Rousseau enthusiast, certainly, even Alex Katz, Philip Evergood and Milton Avery. His work vibrates with the ghosts of artistry past.

For many North American artists and their audience the abandonment of subject was a wanton fall into nothingness. Nor was it a preferred mode for Bates, who stressed the importance of human connections. It is interesting that while he had trouble appreciating the art of Jackson Pollock, which he saw in London, he did voice an enthusiasm for Rothko, de Kooning and Gorky. But despite his experimentation with abstraction, Bates maintained his representational preferences. He bought work by Rouault and admitted that Henri Rousseau was an important mentor. What Bates admired about “naïve” painting was its ability to convey human emotion. “Naïve painting” he observed in 1934,

is more emotional than painting built on a theory or method invented by the intellect. And this lack of an accepted method or theory has the virtue of allowing it to be intensely individual, full of the personality of the painter…. In the subjects chosen we see an absorbing interest in people and all those things commonly used by them…. The naïve painter is a Humanist; making plastic comments on the residue of daily life.

Bates seems to be talking about himself.

In his later years he was pushed aside by the growing critical preference for another kind of Modernism and for an American style of painting which was larger in scale and less insistent on the human voice. As he put it in the early ’60s after being rebuffed by a Toronto dealer:

I am an artist, who, for forty years

Has stood at the lake edge

Throwing stones in the lake.

Sometimes, very faintly,

I hear a splash.

Nevertheless, in his lifetime he achieved a certain measure of recognition as a player in the evolving Canadian art scene; both Dennis Reid and Barry Lord included him in their divergent histories of Canadian art. Kathleen Snow’s biography gives us many of the reasons why that recognition was deserved. Maxwell Bates: Biography of an Artist may not be the last word written about this difficult and elusive artist but its impressive accumulation of detail makes it a useful and vocal contribution to that continuing conversation. ♦

Marilyn C. Baker teaches Art History at the University of Manitoba in Winnipeg.

Maxwell Bates: Biography of an Artist by Kathleen M. Snow, University of Calgary Press, 1993 Hardcover, 278 pp., $39.95