Merz Bow

“Enfin a Paris!” proclaim the posters, and where better to mount the apotheosis of Kurt Schwitters than in a peeling, polychrome temple to Gesamtkunstwerk, the Centre Georges Pompidou. Exhausting, though by no means exhaustive, the Schwitters retrospective is a well-planned outing through nearly 40 years of personal production, 1910 to 1948. Its strict biographical order is disrupted only once, by a small, enriching exhibition of friends and collaborators like Hans Arp, Hannah Höch, Raoul Hausmann, Theo Van Doesburg, El Lissitsky and Paul Klee. Schwitters, we are reminded, was never alone in his areas of activity, but unique in his capacity to see through and synthesize the nominally antithetical movements of the day. Frustrated in his attempt to join the Berlin Dada, he comes down to us as Dadaish, or rather anti-Dada, just as he is by stages anti-Expressionist, anti-Bauhaus, anti-Constructivist, profoundly antiGesamtkunstwerk and purely Merz.

At the Pompidou, 14 rooms were dedicated to Schwitters’s progress through painting, collage, sculpture, poetry, typography, graphic design, environments and performances. A fifteenth added a modest sampling from another 4,000 works, figurative or landscape paintings that must remain hors concours at this modernist seat of judgement. The catalogue expounds what the epilogue suggests: representation (he even photographed!) and abstraction intertwine through Schwitters’s work. Ostracized by the agit-artists, persecuted by the lowest higher authorities, ridiculed, twice exiled, then (absurdly) interned for his German nationality, Schwitters was preserved by his senses. Indeed, if there were ever an example of the restorative power of art, it is Schwitters’s refuge in Norway, a ten-year period of romantic landscapes flowing into organic constructions, the most seductively beautiful passage in his work. Here we see the appetites of the man, and their nourishment, gathered through the eyes, the memory, the instrument and the hand. The Norway that Schwitters imagined from nature is the exhibition within the exhibition that underscores the sensuality of the rest.

But the Schwitters ‘finally in Paris’ aspires to comprehensiveness by accretion, to the complete oeuvre as ‘Gesamtkunstwerk’, as total work of art. The full tribute included recitations of his poetry, and Merz Variétés, a cabaret based on Schwitters’s writing by the Montreal company, Théâtre Ubu. Founded in 1982, this Montreal theatre has developed a specialized repertoire of musical theatre inspired by the work of artists such as Tzara, Picasso, Jarry and Beckett. Based on the success of his Merz Opéra (1987) company director, Denis Marleau, was asked by the Centre Georges Pompidou for a substantial encore—a second cabaret in hommage to Kurt Schwitters. Merz Variétés premiered this winter in Paris, featuring texts translated and adapted by Friedhelm Lach and Marleau, and original music by Robert Normandeau. Four men and two women performed their exuberant comedy-collage on a set designed by the sculptor Michel Goulet.

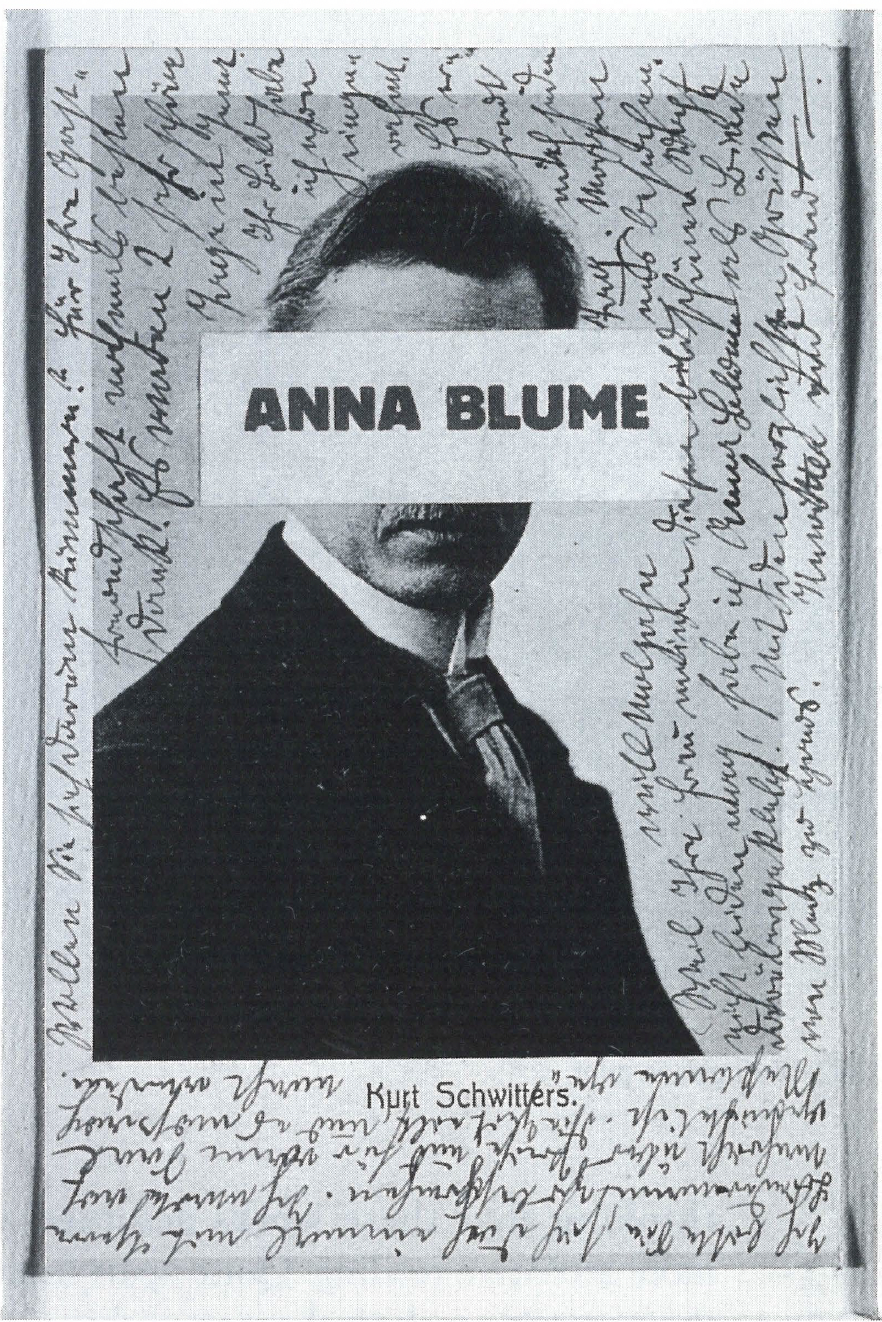

Kurt Schwitters, Portrait of Kurt Schwitters, post card, Galerie Gwurzyuska, Cologne.

Though not strictly accurate, this cabaret was a permissible flight of fancy, in the spirit of “Gesamtkunstwerk,” but loosely so, as Schwitters himself took part in it. At considerable distance from Bayreuth, Schwitters was never drawn to the mythic sub-strata of nationhood, nor did he marshall the theatrical arts into Wagnerian spectacle. His work was always intimate, scaled to his own body, shaped by small incidents of analogy and accident. Who else but Schwitters would include in a poster campaign for the Hannover tramway system the following assurance to the traveller: “Your tickets, your used tickets, are yours to keep.” Schwitters mobilizes not the ‘Volk’, but the detritus and patterns of their physicality, language and society. This is curator Serge Lemoine’s real contribution: through his massive and linear assemblage we can see the imprints of different places and cultures on Schwitters’s work.

It all begins, of course, with Merz, though an Expressionism comes first, as an anticipation of Merz in the manner of passionate contrasts, raised brush strokes and Phileban forms. By 1918, Schwitters is committed to a practice of radical distillation. His drawings become primitivist scrawls and childish outlines; his paintings are the emptying of his pockets, the puzzling together of the studio and the sidewalk; his poems are the moonstruck babblings of an oral engineer.

The catalogue illustrates well the sublime plasticity of Schwitters’s writing by reproducing four different French translations of the famous An Anna Blume (1919), four versions that agree not at all. The cult of Anna Blume comes to life through a taped oral recitation, piped through speakers into the exhibition hall. And the red and white Anna Blume sticker that sparked off a play for six actors (Schwitters, Höch, Hausmann, Nell and Theo van Doesburg, Midia Pines) and one conductor on a Dresden tram also functions as self-cancellation on a Schwitters postcard (1921).

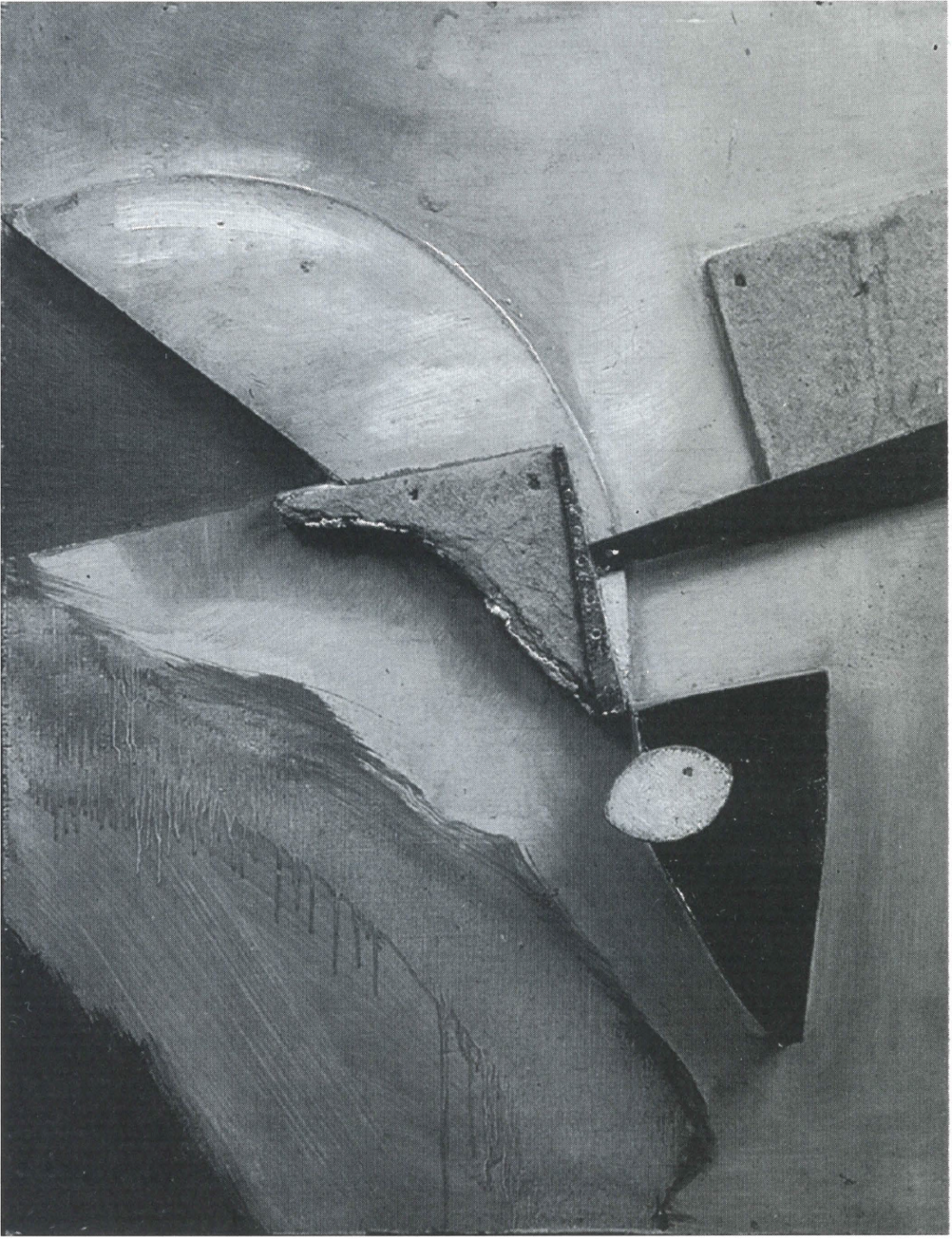

Kurt Schwitters, Untitled, 1934-1937, Galerie Natalie Seroussi, Paris.

But for all the pleasures of the avant-garde recollected, the revelations of this exhibition come from close, comparative study of Schwitters’s collages, drawings, paintings and constructions. “Only the first line (on canvas) can be relatively arbitrary; every line that follows must present in relation to the first the angle prescribed by the natural model.” In a seminal essay on Merz, written in 1920, Schwitters explained the apparent recession of nature in his work, in correspondence to his interest in the internal harmonies of a two-dimensional work. Each of his collages, it seems, must also start from an object or a relationship, but the absolute fusion of elements and colours obscures the key, keeps the work’s secret. Schwitters’s early work is full of such mysteries and suggestions, some of which are lost in the regulated environment of a museum. The depths of Blue (1923-1926) should be in constant transformation, as light moves across the raised, painted surfaces of the work. This for most of us will happen only in our dreams. Schwitters made certain provisions for dreaming. His series of inlaid boxes, made in collaboration with Albert Schulze, is said to be filled with disparate objects gathered by Schwitters for his collages, but later judged incapable of formal integration and forever hidden from view.

The increasing three-dimensionality of his work sheltered other such fetishes. Merz paintings in high relief led to assembled polychrome sculptures (Constructivism into Monstructivism), then to the organic architecture of the Merzbau, the progressive transformation of his atelier into a cavernous grotto of curiosities. The original Hannover Merzbau succumbed to Allied bombing. Its facsimile erected in Paris has been shown in other, more didactic exhibitions. There are photographs and written accounts that serve the object better. The model is a sad and haunted affair that would better have been omitted from an event otherwise so charmed by the touch and the voice of the artist.

The last two chapters of Schwitters’s life are his years as a political exile: Norway in the ’30s, then England until his death in 1947. They are naturally very different. Norway recharged Schwitters, succoured him with the elements of a voluptuous abstraction; wartime England clamped him down, impoverished his materials, tainted his imagery with irony. The Proposal of Marriage (1942) is an amusing bit of kitsch, with the traditional tableau invaded by comestibles, but the too broad social satire belongs to Hogarth. Schwitters worked best at the last from a storehouse of memory, picking up the threads of projects unfinished, like a series of plaster sculptures, Plaster with Hook (1945-1947) or Chicken and Egg (1946). His methodology, explained in a letter, is both Merz and anti-Merz: “I buy a bone and give it to a dog who gnaws what he thinks is gnawable, then I rebuild with plaster what is left according to the laws of movement in art. The result is not bones, but sculptures.” An art upheld by the nature within. ♦

“Kurt Schwitters,” Centre Georges Pompidou, November 24, 1994 to February 20, 1995; Institituto Valenciano de Arte Moderno, Valencia, Spain, April 6 to June 18, 1995; Musee de Grenoble, Grenoble, September 16 to November 27, 1995.

Martha Langford is Border Crossings’s Contributing Editor in Montreal.