Material Self: Performing the Other Within

Curated by David Liss and Bonnie Rubenstein, MOCCA’s “Material Self: Performing the Other Within,” a major exhibition at the Scotiabank CONTACT Photography Festival, looked to eight international photographers who use fantasy and masquerade as conduits for self-knowledge and personal transformation. For the most part, these mostly young artists saw CONTACT’s “identity” theme not as an occasion to hide behind simulacra and masquerade but rather as an opportunity to disclose truths about their inner lives, delving deep into family history or cultural heritage. Kobe-born Swiss photographer David Favrod, for example, investigated his half-Japanese origins in 12 photographs of varying sizes. The largest of these, Vent Divin, 2013, shows him standing on a riverbank in a kamikaze pilot’s uniform. On his shoulders sit fragile-looking wings made from twigs, string and white cloth, recalling the mythological figure of Icarus. Favrod looks for “the other within” through the prism of such experiences as his maternal grandparents’ reluctance to share stories about the war and the Japanese embassy’s refusing to grant him double nationality.

“Material Self: Performing the Other Within,” 2014, installation view, Museum of Contemporary Canadian Art (MOCCA), Toronto. Courtesy MOCCA. Photograph: Toni Hafkenscheid.

South African Mary Sibande, whose matrilineal ancestors were domestic maids, also sees fantasy as potentially transformative. Through five photographs of life-size sculptural tableaus, Sibande tells a story about her alterego “Sophie” who escapes life as a maid by imaginatively transmuting into icons of aristocratic empowerment. In Her Majesty, Queen Sophie, 2010, the blue maid’s uniform becomes voluminous, acquiring ruching and a train. Framing her head, four red beams radiate from a colourful beadwork collar, while long strings of beads drip to the floor. On a darker note, there is no outside context for Sophie’s imaginary transports, which appear to be shot in empty galleries or studios.

Swiss Namsa Leuba also probes her mother’s heritage in the series Ya Kala Ben, 2011, using fabrics, twigs, rope and other props to reimagine Guinean locals as tribal statuettes. There is something disorienting about these decontextualized mise-en-scènes, which play on Western fantasies about African authenticity while risking outrage from the communities where they were staged because of their failure to conform to actual religious systems. However, if Ya Kala Ben may be read as a critique of ethnography’s pursuit of authenticity, Leuba’s other series, entitled The African Queens, 2012, looks and functions like fashion media, a type of photography where we expect to encounter tribal symbols divested of their cultural significations. Given a collection of designer knits to feature in her spread for New York magazine’s website, Leuba researched her Guinean ancestry before styling and posing three non-models she picked from the streets of Paris, finishing off her tableaus with tribal jewellery, rope, feathers, logs, floral fabric and reflective foil.

Like Leuba, French photographer Charles Fréger toys with ethnographic convention. Shot between 2010 and 2011 in 18 countries across Europe, each photograph in Fréger’s “Wilder Mann” series presents a folkloric “creature” that harks back to paganism. In one, needled branches transform a man into an animate fir tree at a Swiss festival; in another, three fur-covered, long-headed babugeri—Bulgarian mummers—herald the distant coming of spring. Mostly made from plants, animal skins and bones and colourful textiles, these costumes were designed for movement, so their isolation against wilderness backdrops sometimes makes them look static, like specimens under glass. In this respect, Meryl McMaster’s fantastical entities offer a dynamic alternative. Only 26 years old, the Canadian artist explores her Cree and Scottish ancestry in photographs like Wind Play, 2012, which captures her performing in a snowbound landscape, shaking the blue fur or plumage (made of unblown balloons) that completely covers her body. Unlike Fréger’s more ethnographic camera, McMaster’s translates her own bicultural identity into otherworldly situations where human beings transform into animals and vice versa.

Mary Sibande, Her Majesty Queen Sophie, 2010, digital print, 110 x 80 cm. Courtesy the artist and Gallery MOMO, Johannesburg.

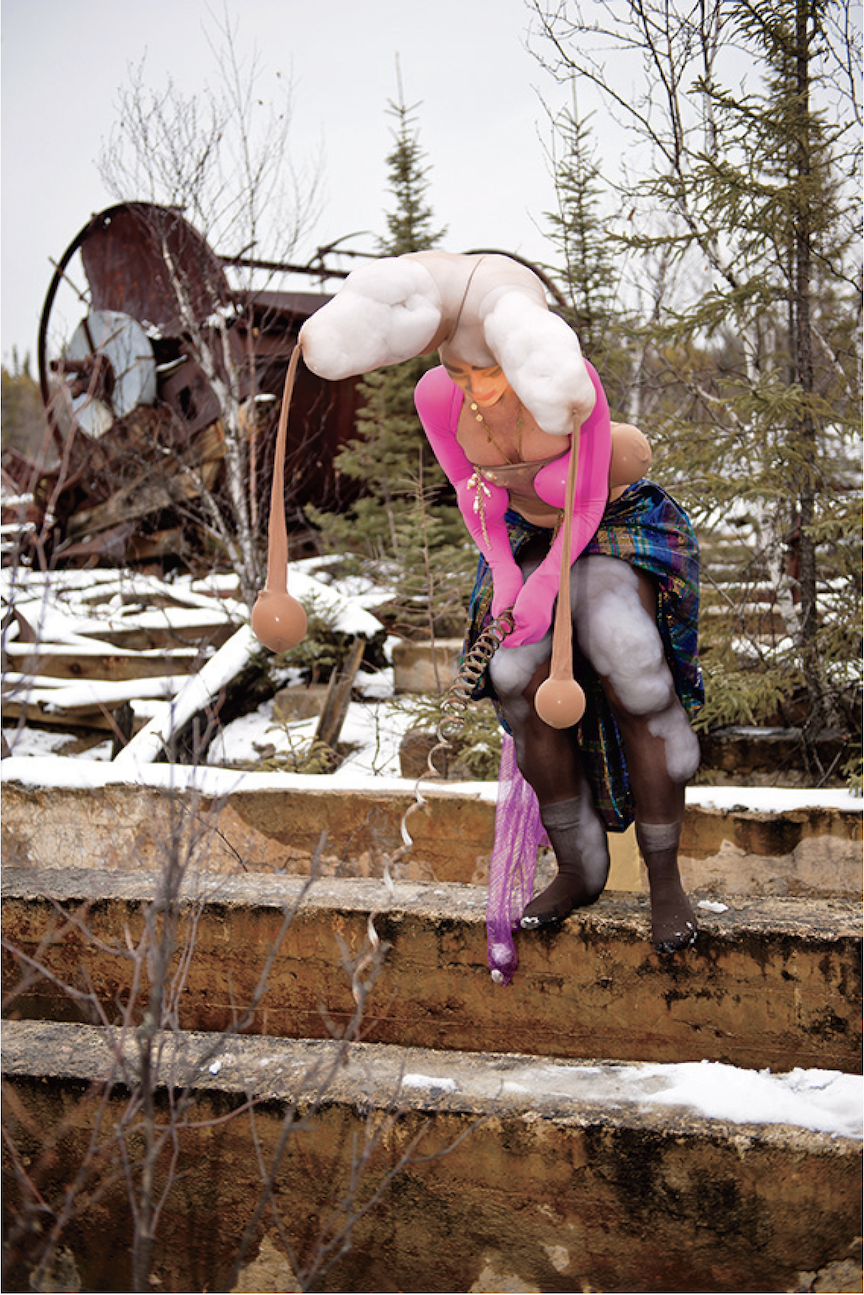

In 2011, Canadian Dominique Rey photographed and filmed herself in a similar way, disguised as the Erlking, a malicious creature from German folklore that preys upon wanderers in remote places. Performing in such locations across Manitoba and Alberta, Rey gave herself horns, bulbous limbs and oddly coloured skin using simple materials like nude pantyhose, cotton batting, fluorescent fabric and water balloons. Sigmund Freud famously called unheimlich—“unhomelike” or “uncanny”—that sense of the familiar suddenly rendered strange, coupled with the suspicion that we might be living in an animist world. Rey’s Erlkings deliver on both counts: otherworldly yet mundane, their bodies look made from flotsam and jetsam, born of environmental disaster in pristine winter landscapes.

Like Rey, Dutch photographer Hendrik Kerstens seeks sublimity through ordinary materials in four photographs taken between 2007 and 2012. The oldest artist here by a wide margin, Kerstens poses, illuminates and photographs his daughter Paula in a manner reminiscent of Johannes Vermeer’s portraits, simulating elements of 17th-century Dutch costume with kitchen items. Placed on the woman’s head, a white plastic bag resembles a bonnet with turned-up wings, while a stack of doilies fitted around her neck becomes a lace ruff.

The series of photographs that feels apart from the rest is Tomoko Sawada’s “OMIAI,” 2001. While most of the artists in “Material Self” either craft or gravitate towards highly expressive, even ludic characters and circumstances, the Japanese photographer deliberately holds back. Through 30 studio portraits displayed in three vitrines, Sawada subverts the photographic language of traditional matchmaking cards exchanged by a potential couple’s parents. Posing for these portraits herself, she often changes hairstyles as she experiments with Western attire and kimonos alike, recalling Cindy Sherman’s “Untitled Film Stills,” 1977–80, the iconic series of 69 black-and-white photographs which embodied different cinematic stereotypes. Like Sherman, Sawada seems to dispute the idea of masquerade as a vehicle for self-disclosure, since we never get a sense of her inner life. The changing expressions on her face look artificial in every portrait, a hermetic antidote to the flights of fantasy everywhere else. ❚

Dominique Rey, Thunderhead, 2011, C-print, 30 x 20 inches. Courtesy MOCCA.

“Material Self: Performing the Other Within” was exhibited at the Museum of Contemporary Canadian Art, Toronto, from May 1 to June 1, 2014.

Milena Tomic writes about contemporary art and teaches art history at OCAD University and the University of Toronto Mississauga.