Mary Kavanagh

“You’re being very, very serious with me…. You’re not really responding to all of my attentions,” remonstrates artist Mary Kavanagh to a cast bronze bust of Georgia O’Keeffe made in 1967 by Una Hanbury. With video, photographs and handfuls of earth, Kavanagh’s installation Seeking Georgia explores the cultural residue of O’Keeffe’s New Mexican landscapes, which are inevitably filtered through the powerful O’Keeffe industry. The intersection of academic, museological, commercial and tourist practices, all gender inflected, produces a rich field of inquiry that Kavanagh mines with acuity and deadpan humour. The artist’s meticulous, almost compulsive, record of her pilgrimage to O’Keeffe’s painting sites manages a delicate balance: it is at once a powerful critique of disciplinary paradigms that authenticate the art world and a genuine tribute to a feminist pioneer.

Dominated by a grid of 24 square plinths, each containing handfuls of earth, Kavanagh’s installation invokes the authority of museum display techniques. From a distance, the soil resembles a scientific collection of earth pigments: burnt sienna, burnt umber, raw umber. Aestheticized in their glass cases, each collection becomes an object of visual interest, yet the included debris—broken glass, twigs and rocks—disrupts any ideal of purity that might have been expected. The realization dawns that this is not archaeological material in the usual sense, nor is it some scientific analysis of earth pigments in O’Keeffe’s paintings. Instead, it is a collection of souvenirs, or perhaps fetishes, given meaning and significance by the gallery’s authenticating aura. The authority of the museum is again invoked by discrete labels with information regarding the site of soil collection as well as catalogue raisonné numbers of corresponding O’Keeffe paintings, which are taken up in nearby wall panels. Like extensive didactic material in a natural history museum, the wall panels include Kavanagh’s contemporary photographs of the soil collection sites, reproductions of O’Keeffe’s paintings linked to the sites and academic documentation of each painting’s various titles in supposedly authoritative texts. The result is an obsessive record of places, paintings and texts that lays bare the impossibility of understanding O’Keeffe’s works outside the cult of personality.

The wall texts parody the kind of scholarship begun almost a century ago when Picasso’s dealer, D.H. Kahnweiler, photographed Cubist landscape sites to lend realist credence to Cubist abstraction. The comparison of photograph to painting can be illuminating, but too often it reduces landscape painting to a transcription of the visible. It can deaden any broader inquiries about the ideology of place, about how aesthetic choices signify allegiances to larger narratives, such as the role the images play in the construction of a national myth of the West’s settlement, but in Kavanagh’s hands, the comparison heightens our awareness of O’Keeffe’s iconic status and its touristic effect on scholarship.

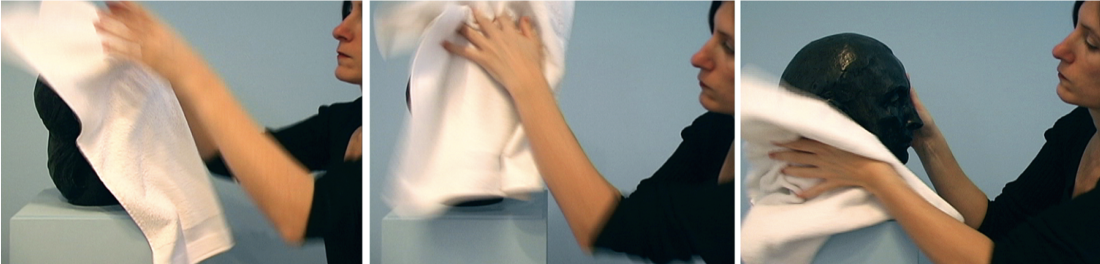

Mary Kavanagh, Seeking Georgia: Bath, 2006, video still sequence. Courtesy the artist.

The wall texts are small, encouraging serious, even reverential, examination and taking the critique of museum discourses to a more conceptual plane. Kavanagh uses the chapel-like space of the gallery to great effect, playing with the idea of gallery going as akin to religious ritual, a parallel that transfers authority and aura to art. Examining the wall texts, the viewer performs a kind of Stations of the Cross, in effect retracing Kavanagh’s pilgrimage, all the while being pulled forward by the whispered voice beckoning from behind a partial wall at the far end of the gallery.

At what you might call the altar end of the gallery, a trinity of videos reveals the climax of the Kavanagh/ O’Keeffe relationship. The left monitor displays a bronze bust of Georgia O’Keeffe, shot in profile, with Kavanagh’s hands lovingly attending to its hygienic needs, even cleaning Georgia’s ears (we’re on a first-name basis now) with meticulous care. On the right monitor, Kavanagh’s face comes into frame to give the bust of Georgia a quick, almost exploratory, kiss, followed by longer, more intense, yet strangely dispassionate ones. Surprisingly funny, the kisses reshape the rest of the exhibition, bringing its absurd elements, irony and critical edge into focus.

Kavanagh’s voice emanates from the central monitor, where the artist whispers into Georgia’s ear, “I’d like to talk to you about moving images.” The ensuing conversation explores the central issue of the exhibition: the construction of O’Keeffe’s image, both by the artist herself in documentaries made during her life, and now as controlled by the Georgia O’Keeffe Foundation. The discussion, albeit one-sided, is very intimate, like serious girl talk: what O’Keeffe was wearing, how it came across, how particular images were framed, and finally whether Michelle Pfeiffer would be a good casting choice in a new movie. Yet Kavanagh herself is clearly vying for the role. The videos exploit visual similarities between the artists: both women have an austere, serious demeanour, the similarity heightened by hair pulled tight to the nape of the neck, aquiline noses, and striking profiles. Kavanagh may be worshipping at the altar of Georgia but, like any good acolyte, she seems poised to step into the icon’s role.

As the viewer leaves the exhibition, the bronze bust of O’Keeffe watches over the proceedings like a secular Last Judgement transposed from a mediaeval church. I think Georgia would approve. ■

Mary Kavanagh’s Seeking Georgia exhibited at the Southern Alberta Art Gallery in Lethbridge, Alberta, from January 22 to March 5, 2006.

Anne Dymond teaches art history and museum studies at the University of Lethbridge.