Martin Pearce

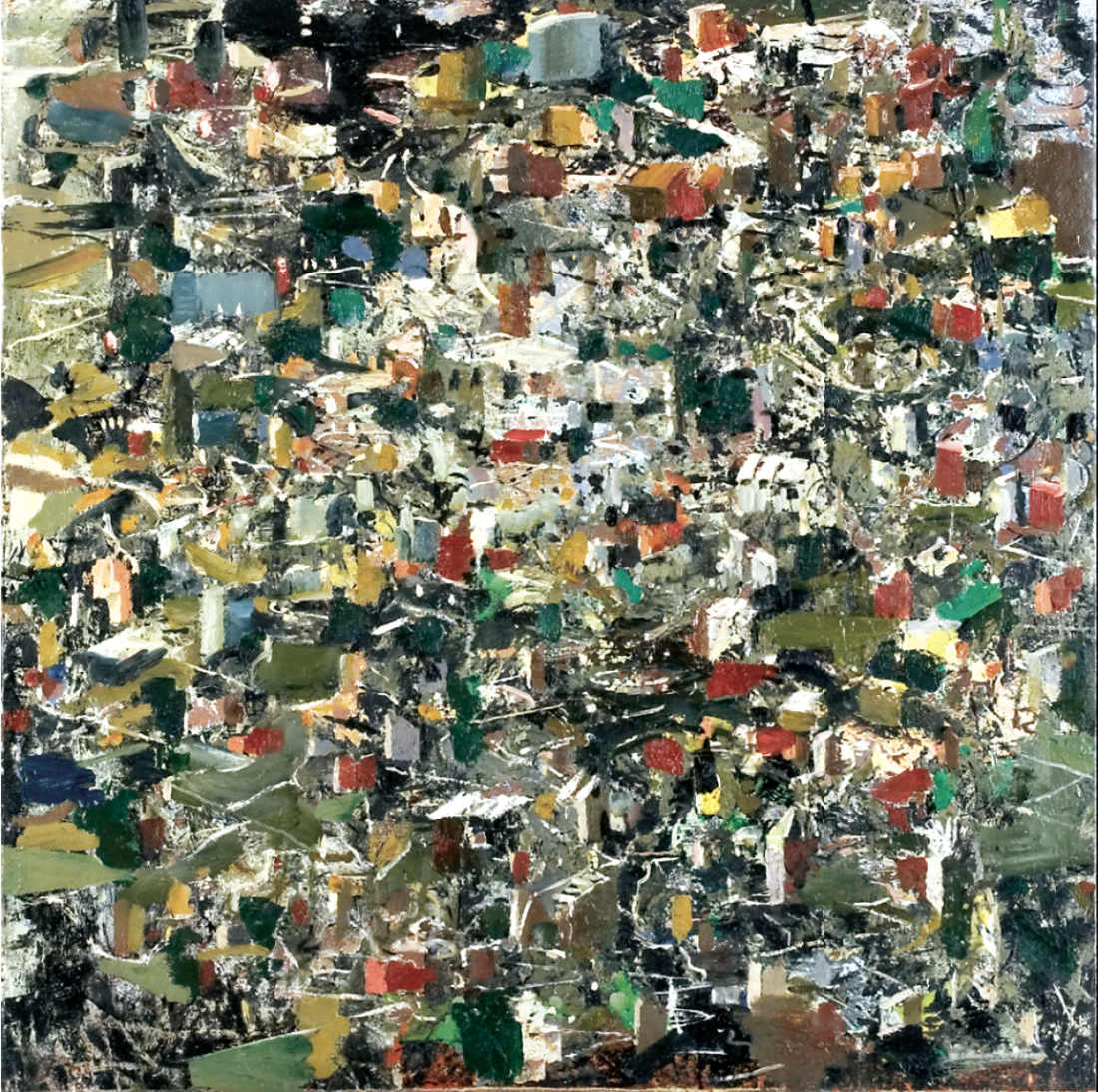

In one sense, the new works by Toronto artist Martin Pearce can be seen as pure painting, in that his concerns focus mainly on painting itself—its tradition and means. However, his is not a strictly modernist enterprise, but relies on a destabilized field, within which the position of his work is downright slippery. Moving from a series of purely abstract works completed in 2003 and 2004, Pearce felt the urge last year to reinsert representation into his painting. He began embedding small, rectangular areas of colour into the all-over chaos of his impastoed and scraped surfaces, and then, abutted with these, he painted other rectangles set at an angle, or, at times, a parallelogram above—which then formed images that can be read quite easily (in fact, automatically and irresistibly) as tiny buildings in some sort of fantastical landscape setting. This minimal amount of representation was intended to invigorate the otherwise abstract works, and many of the colours and shapes of the buildings were based on details observed by the artist in his daily life. Pearce uses a fairly subdued palette and works wax into his oil paint. Rather than having a luscious feeling, however, his paintings seem rather arid and restrained. This could be a result of his insistent scraping down (and then rebuilding) surfaces while he is working. Viewers readily sense the importance of relative scale while looking at these works, as the size of the brush marks, the “buildings” and other taches and facets of colour and texture are in a finely energized relationship with one another and with the overall, relatively small, size of the canvases.

It is intriguing to track the path or progression in this new series because the earliest paintings (for example, Late Victorian or Around the Old Town) are depictions—emphatically and unambiguously—of haphazardly arranged clusters of 100-year-old-looking domestic and larger scale buildings. Moving on from these works, Pearce appears to have decided to up the ante and have the works hover in a netherworld of partial abstraction with only traces of representation. So, for example, in Ridge Modelling, from later in 2005, the painting first reads as totally abstract, but then, continuing to look at it, tiny ochre and burnt sienna-coloured structures suddenly begin to visually pop up from the jagged rocks and hills, just the way the bit of text inside a toy eight ball floats up into view when animated to provide an answer.

Martin Pearce, Around the Old Town, 2005, oil on canvas, 32 x 30”. Photo courtesy the artist.

In fact, looking at Pearce’s paintings underlines how very little humans need to be given in order for a perception of a coloured shape to register as mimetic meaning. So a couple of abutting rectangles will pop forward into our image catalogue as two sides of a building, without any further prompting or detail. Changes of hue or tone between the rectangles imply the effect of directional light and give the viewer the notion of three-dimensional forms being depicted. Our eye-brain connection does this sort of recognition and interpretation unbidden.

Pearce seems to have wanted to explore a dialectic set up between those sacrosanct binary poles of abstraction and representation that were established in the early 20th century. There appears to be a source of energy from that place for these works to draw upon, even though there is a disturbing, destabilized quality to it. While not engaging in the ploy of postmodern hybridity per se, these works are definitely deconstructing the notion of modernist purity while continuing to affirm the physical process of painting; that is, of how a painting is made.

It is always interesting to see what any of us will bring to our interpretation of a work in any sort of medium, no matter how minimal the image being contemplated. For example, to me, some of Pearce’s townscapes call to mind the illustrations of Mitsumasa Anno, particularly his wordless “journey” through mediaeval walled towns and landscapes. And I was reminded of David Milne with the small group of paintings in the show that are based on the sensation of a quarry, and do not, in fact, contain representational elements. Pearce himself says that he had in the back of his mind the detailed mediaeval landscapes in the colossal Sienese frescoes on the Allegory of Good and Bad Government by Ambrogio Lorenzetti.

Serious painters at work right now face a quandary: they may wish to further the tradition of the medium, using their own creative means or style, and yet they are up against what is viewed as the overall exhaustion and dissipation of the art form, in the face of the ascendancy of the new media. How does a painter proceed without the effort’s taking on the character of Hesse’s glass bead game for the effete? But, like the bonfires that were set alight on hilltops in olden days to signal news across the countryside, the practice of painting is somehow still alive in the hands of some few, talented practitioners. Their works call out to a specialized audience who continues to take an interest in the art form that has, for a long time, been more than a mere medium— for, in fact, painting can be a way of living, a world. ■

Martin Pearce’s “Where There’s Space” exhibited at the Glenhyrst Art Gallery of Brant in Brantford from March 18 to May 21, 2006.

Liz Wylie is a curator at the University of Toronto Art Centre.