Mark Rothko

An artist’s disclaimer from Mark Rothko’s 1961 retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art is reprinted at the entrance to Tate Modern’s “Rothko: The Late Series”: “If people want sacred experiences they will find them here. If they want profane experiences they’ll find them too. I take no sides.” The battleground gallery, already visible to those queuing up at the entrance, is a curator’s attempt to present the unrealized space Rothko imagined for a series of murals he created in the late 1950s. This collection of 30 canvases, collectively known as the Seagram murals, familiar to many visitors from the small collection permanently on view at Tate since 1970 and now at Tate Modern, are among the most mythologized of post-war art. The story of their creation—out of a 1958 commission for seven murals to adorn a dining room at the Four Seasons Restaurant in Mies van der Rohe’s Seagram Building, and Rothko’s ultimate rejection of the commission two years later—is central to the Rothko legend. The tale of the defiant artist, protecting his poetry from commerce’s perversions has been retold and embellished for over 40 years. It gained real momentum after the artist’s death in 1970, making Rothko a folk hero for those who cannot help but feel nostalgic reading Vasari’s Lives of the Artists. In many ways, the story has become the defining episode in the artist’s life history: author James EB Breslin uses it to introduce Rothko in his 1993 biography.

The dark palette and serial fascination that define Rothko’s oeuvre in the final decade of his life first emerged in 1958, making the Seagram commission a point of departure for any show of Rothko’s “late work.” The Tate Modern exhibition, by Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art Achim Borchardt-Hume, tries to convince visitors that the compelling narrative didn’t stop when Rothko dramatically rejected the Seagram commission in 1960. It reminds visitors that Rothko returned to the murals again and again, obsessively reworking their arrangement and trying to find an adequate resting place for his site-specific installation that was lacking a site. His preoccupation with architectural spaces and serial work also manifested itself after the Seagram commission, in canvases from the 1961 Harvard Holyoke Center commission, 1964 “Black-Form” series, 1968 “Brown and Grey” series, and 1969–70 “Black on Grey” series, many of which are included in the show.

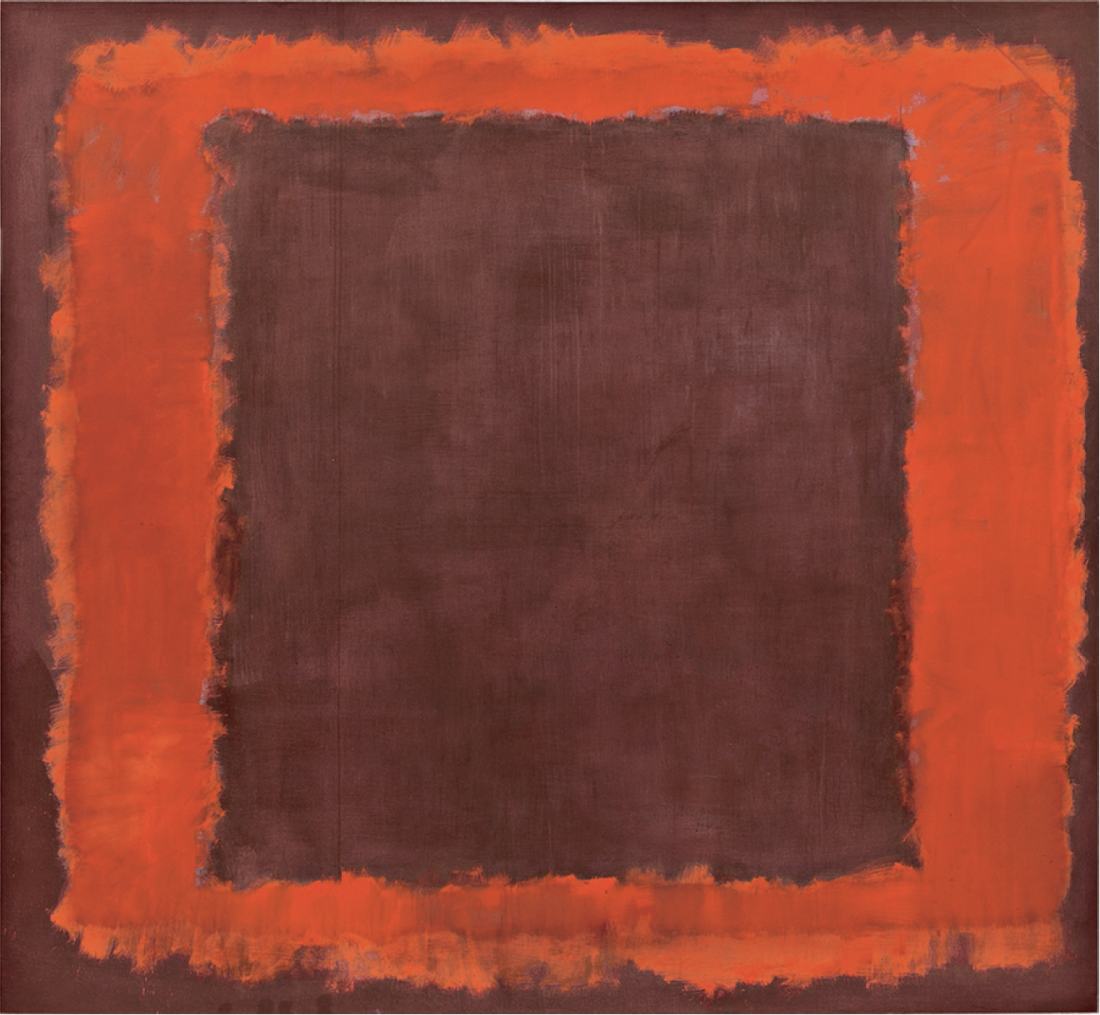

Mark Rothko, Untitled (Seagram Mural), 1959, oil and mixed media on canvas, 265.4 x 288.3 cm, National Gallery of Art, Washington, gift of the Mark Rothko Foundation, Inc. © 1998 by Kate Rothko Prizel and Christopher Rothko.

Rothko never specified which seven of the 30 canvases were to be installed in the Four Seasons Restaurant. In an unprecedented selection from the mural series, eight canvases from Tate’s collection are hung in the exhibit with their counterparts on loan from the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC, and the Kawamura Memorial Museum of Art in Sakura, Japan, where the exhibition heads next. The Seagram murals selected for display suffer in the exceptionally awkward gallery space. They hang in a large, central room that is a heavily trafficked corridor connecting many of the exhibit’s galleries. If this was the curator’s attempt to imagine the intended setting of the Four Seasons Restaurant dining room, it is a grave insult to the restaurant.

However, upon entering the gallery, I was acutely aware of how public the Rothko viewing experience would be. The room’s crowds transform the classic private Rothko experience into a kind of performance where the wildly expectant eyes of other visitors are felt at your back while you move in to inspect any particular mural. It does not help that the size and orientation of the Seagram murals is intentionally disorienting. Rothko, reeling from the uncomfortable popular acceptance of his work in the mid-’50s, created these murals to reestablish the seriousness of his endeavour. Those accustomed to his classic works of the late ’40s and ’50s find themselves disarmed by the new horizontal orientation and dark, geometric forms of the Seagram murals. Like Poe’s perfectly logical Prefect of Police hopelessly searching for the purloined letter, the viewer, approaching a Seagram mural for the first time, sees everything but the painting. Retreating to metaphor, the allusion is to death or the apocalypse. Author John Banville described his experience of the color in the Tate Modern Seagram murals as seeping “through the canvas like new blood through a bandage in which old blood has already dried.” This is a fine defence for a short time, but any viewer quickly seeks refuge in one of the satellite galleries of later paintings.

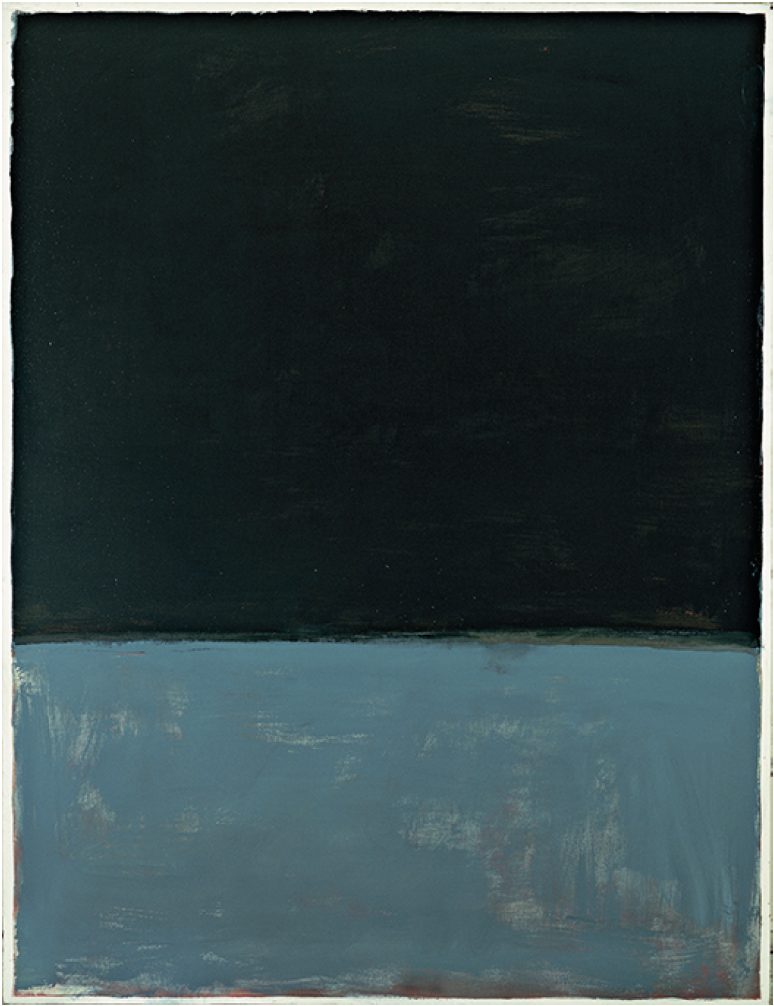

Mark Rothko, Untitled, 1969, acrylic on canvas, 229.6 x 175.9 cm. National Gallery of Art, Washington, gift of the Mark Rothko Foundation, Inc. © 1998 by Kate Rothko Prizel and Christopher Rothko.

The most rewarding path out of the central Seagram room leads to a gallery of Rothko’s final works, the “Black on Grey” series from 1969 to 1970. These smaller paintings on canvas are even further removed from the classic format. In each panel, a heavy black slab weighs on a foamy grey strip. In 1968, Rothko suffered a physically incapacitating aortic aneurysm. His doctor recommended avoiding painting formats larger than 40 inches in height. At this scale, Rothko departed from his experimental priming agents, choosing instead white gesso, a primer with a long tradition. On the “Black and Grey” canvases, the gesso peeks through the frosting-thin layer of grey acrylic. The subtle white edge found in these paintings, another departure for Rothko, only draws greater attention to the painting’s life as an object in the world.

This final series strips the artist’s ambition down to its basic elements. Unlike those in his better-known “Black-Form” paintings of 1964, the black color fields in these canvases do not even flicker. The aneurysm left Rothko in terrible health. Any faith he had in the painterly illusion seems to have seeped out as he returned to painting following rehabilitation. Robert Motherwell once told an interviewer asking about his friend Mark Rothko, “he used to say no one understood how aggressive his works were,” that “a picture is good if you can endure it.” Tate Modern’s “Rothko: The Late Series” finds the painter at his most convincing. ❚

“Rothko: The Late Series,” curated by Achim Borchardt-Hume, was exhibited at Tate Modern, London, from September 26, 2008, to February 1, 2009.

Alexander BD Kauffman has worked at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the Museum of Modern Art, and Harper’s Magazine. He contributed a catalogue essay for Patrick Lundeen’s Spring 2008 Blue Yodeler exhibition at Wetterling Gallery in Stockholm.