Mark Neufeld

In the weird and exacting culture of historical re-enactment, a “farb” is what hardcore participants call the wannabes: the jerks who turn up to the Battle of Gettysburg, 1863, in machine-stitched uniforms, snacking on bananas and carrying rifles from 1902.

“Re-enactments,” Mark Neufeld’s complicated and engaging show at the University of Winnipeg’s Gallery 1C03, was a celebration of farby aesthetics. The exhibition was cluttered with an assortment of stuff that elaborated on fake-ish histories and asserted the theatricality of looking backwards. Paintings and framed collages were displayed alongside historic depictions of 19th-century Winnipeg and a pair of Frederic Remington’s bronze cowboys; thrifted copper plates adorned with Goodwill price tags shared shelf space with Bertrand Russell’s Wisdom of the West and a gold-sprayed miniature bust with a Greco-Roman vibe.

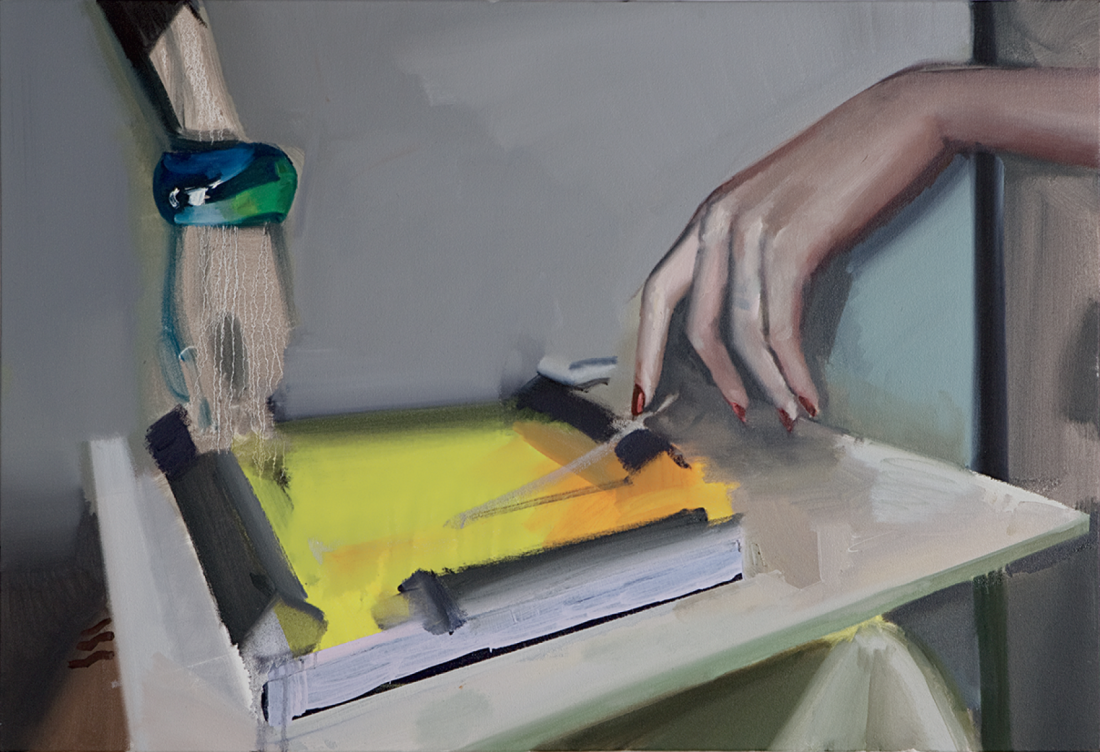

Mark Neufeld, Moving Sculptures II, 2014, oil on canvas, 22 x 30 inches. All images courtesy the artist and Gallery 1C03, Winnipeg.

On six occasions, these objects were handled, stroked, thrown about and admired by two actors—one wore a plastic bonnet, the other a glistening white wig of synthetic hair—in a performance which strung together excerpts from an article on the “History of the Notion of Care” and first-person narratives from two historic sources, the diary of the English “gentlewoman” Isobel Finlayson, and the pseudonymous autobiography of the prostitute and brothel owner, “Madeleine Blair.”

The first time we hear from “Madeleine” she asks: “What is the appeal of an image of a fort?” This question ricochets throughout the exhibit, suggesting a trajectory of connections among the diverse items on display. Some of these links are explicit: a slightly battered catalogue for “Dreams of Fort Garry,” a 1999 exhibition at the Winnipeg Art Gallery, is draped over a mirrored screen. A seven-foot canvas depicts a massively enlarged copy of this catalogue’s front cover, complete with a painting of the cover’s reproduction of a painting of The Forks by W Frank Lynn. Still with me? That painting is part of the WAG’s collection, and it’s odd to think of it sitting in a vault, unseen, while its strange clone, that copy of a copy, is out on display. Large Catalogue Re-production (Dreams of Fort Garry; You are Here) is twinned on the opposing wall by Another Green; Another Screen (Nowhere and Everywhere), a monochrome that doubles as a green screen. These kinds of aesthetic rhymes bounce from piece to piece, establishing a dense thicket of formally fortified conceits.

The real Fort Garry was a Hudson’s Bay Company trading post at the confluence of the Red and Assiniboine rivers in what is now downtown Winnipeg; the front gate is all that remains of it today. The appeal of an image of a fort is that unlike the real thing, it can exist purely in the mind. It can stand in for a vague idea of history, or rootedness, or security. It can be mirrored, reconfigured, repurposed, used as a pictorial unit in a game that is as much about strategies of aesthetic connection as it is about the things that are linked.

Installation view, Re-enactments: The Performance, Gwen Collins as preparator (with Frederic Remington’s Bronco Buster), from “Re-enactments,” November 20, 2014 to February 14, 2015, Gallery 1C03, Winnipeg.

Neufeld’s image of a fort isn’t bound by the details of one specific era, or even tied inextricably to a single place. In “Re-enactments,” Neufeld engages with history in order to play with its forms, jumping from picture to object, from essay to diary, from artefact to stereotype. He seizes whatever is useful, whatever is interesting and fun.

This makes for a refreshingly complex, boisterous and ambitious exhibition. The tricky thing is that in this context, a “take whatever works” attitude inevitably feels imbued not only with creative spontaneity and inventiveness, but also with colonial entitlement. Like re-enactment culture itself, the exhibition largely ignores Indigenous narratives and skirts history’s gaping wounds. Cowboys and whores are brought out to play, but gendered typecasting is only slightly subverted by the whiff of parody in the air. History feels harmless here, neutralized for aesthetic purposes.

I get why Neufeld doesn’t take on the burden of representing what re-enactments tend to exclude. The full history of this place is big and heavy and difficult. It might not even be appropriate for a white guy to tell those stories right now. Neufeld isn’t trying to give us a history lesson—he’s using history-shaped ideas to build complex aesthetic structures. By focusing on the way history looks through the lens of re-enactment, Neufeld has made a decision to keep the trauma of the past out of the field of view.

Mark Neufeld, Building a Fort: The Model II, 2013, oil on canvas, 32 x 48 inches.

Hardcore re-enactors are obsessed with authenticity, but historical re-enactment is fundamentally about turning away from real life. Re-enactors seek a version of the past that has no consequences, no mortality, no future. The reason why re-enactments can never be truly authentic is not that it’s impossible to get decent homespun wool today—it’s that we can’t not know how the battle ends. The one thing that re-enactors are unable to recreate is the innocence (or ignorance) upon which freedom depends. Re-enactors always know the consequences of their characters’ actions, and they do them anyway.

But the farb changes the game. By introducing anachronistic details, farbs contaminate the past, changing it into something different, something new. This is what I think Neufeld is trying to achieve in this exhibition. When he copies the catalogue cover, for example, Neufeld finds a way for it to make sense, in the 21st century, to paint a picture of The Forks at sunset. This impulse is romantic and unruly. It suggests that the past might not be finished, exactly, and that there are ways for it to breed with the present. Its victories, and its demons, are still with us, shaping us, making us new.❚

“Re-enactments” was exhibited at Gallery 1C03, Winnipeg, from November 20, 2014 to February 14, 2015.

Erica Mendritzki is an artist and educator living in Winnipeg.