Marisa Merz

We learn much from the scant published words of Marisa Merz, the Italian artist who, at age 90, is having her debut North American retrospective. In a 1975 interview with French critic Annemarie Sauzeau-Boetti, Merz discusses her interest in the sensation of transparency, remarking, “It’s not just a visual thing, transparency.” Her language—like her work in sculpture, installation, drawing and painting—exceeds the denotative, exceeds its own visuality. She composes a porous space where material properties are things felt as they fold into and out of myriad lyric associations. Perhaps unsurprisingly, Merz is a prolific author of poetry, and her apartment (which she continues to use functionally as a studio to this day) is said to abound with scrawled bits of verse scattered among her drawings and accumulated ephemera. “Marisa Merz: The Sky Is a Great Space” draws its title from one these poems, with the “great space” conjuring cosmic fullness as much as a cavity or gap. The show, which encompasses all five decades of Merz’s production, is a scintillating coming together of transparency as sensation. Merz’s lifetime of work, installed at the Met Breuer in January 2017 and at the Hammer Museum in June 2017, offers her philosophical and material devotion to transparency as a condition of permeability, where spaces, as gaps, allow for a rich intertwining of artworks, exhibition site and the artist’s circuitous career trajectory.

Marisa Merz’s apartment, Turin, 2016. Photo: Renato Ghiazza. Courtesy Archivio Merz.

Merz’s works never exist as autonomous objects. They are enmeshed in the greater whole of her production and within their installation contexts. Curator Leslie Cozzi aptly describes this relationship in terms of “a body to its skin” in the accompanying exhibition catalogue (the first English-language publication devoted to the artist). Concerns around site-related production and material flux are, of course, hallmarks of 1960s art, particularly within Arte Povera—the loose collection of Italian artists identified as such by curator Germano Celant in the late 1960s. Merz is the sole female artist affiliated with the group, and, married to one of the most prominent of the Poveristi, Mario Merz, she has been known throughout her life principally as a wife. Of the Arte Povera artists who sought to collapse divisions between art and life, Marisa Merz’s oeuvre is perhaps the most indivisible from the structures and rhythms of the day-to-day. Merz makes plain the interrelatedness of her work as an artist, wife and mother (to her daughter, Bea), stating in the interview with Sauzeau-Boetti, “Everything was on the same level, Bea and the things I was sewing; I was as involved with the one as with the other.” Nonetheless, Merz’s domestic role was not purely imposed, but an identity over which she had some agency as she sidestepped conventional approaches to an artistic career. During these early years of child rearing Merz was at work on large, hanging aluminum forms entitled Living Sculpture. At the Met Breuer, the exhibition opens with these works, installed tightly against two temporary gallery walls. The confined, frontal installation evokes their hulking presence within the Merz home, where they were made and initially hung. Their relationship to the domestic site of fabrication is further suggested by an accompanying chair, which Merz has reimagined in the same layers of folded and stapled aluminum. These are imposing works, sharp and metallic but simultaneously flexible (Merz hand-folded the aluminum), as they faintly sway with the passing air currents.

Moving past Living Sculpture, the show opened up into a central room flanked by galleries on either side and a smaller rearmost exhibition space. Merz resists dating her work, and the somewhat circular layout of the exhibition echoes her preference for non-linear production, while allowing each space to function as a field activated by her objects. Employing a comparably slow, repetitive process as she did in Living Sculpture, Merz knitted copper and nylon thread into mesh wall hangings as well as small, spiralling forms and sleeve-like letters that spell out “BEA.” A variety of these slight but strong woven works are on view in the middle gallery. Fine, knitted copper squares are affixed to the walls with nails, accumulating in loose arrangements akin to musical staves. A few versions of Merz’s enigmatic Scarpette (little slippers) knitted out of nylon (and occasionally copper wire) are on view in vitrines, looking from a distance like ossified, moth-eaten lace. Merz wove many of these slippers for her own feet, and she sometimes wore them. Even in this conventional museum installation they carry, in the hollowedout recess for her implied foot, the imprint of her body. These objects consist as much of the empty spaces between the strands of material as of the threads the artist painstakingly knitted together.

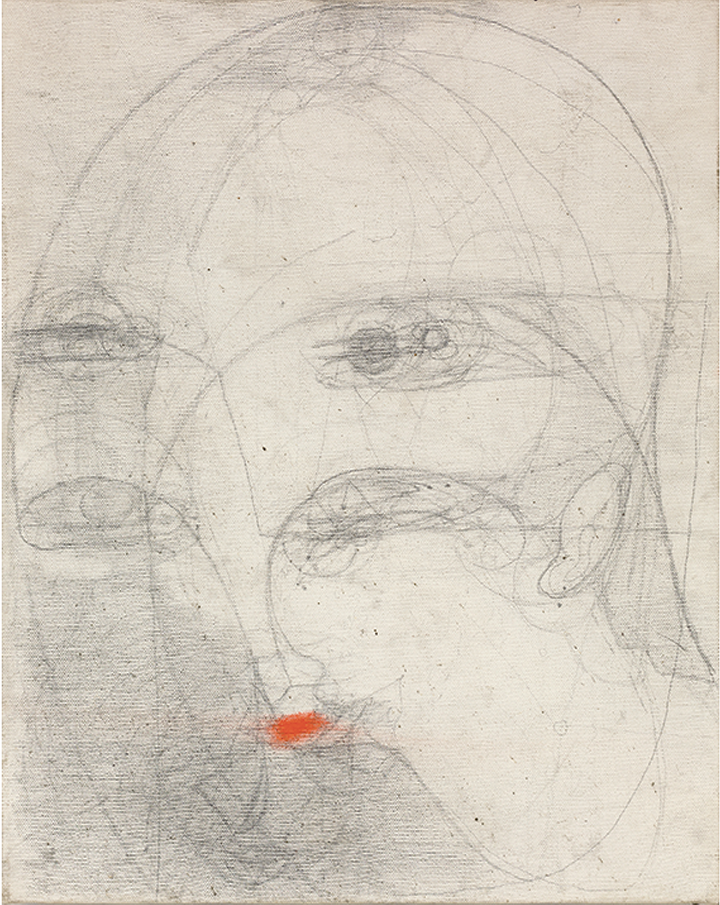

Marisa Merz, Untitled, undated, graphite and lipstick on canvas, 50 x 40 cm. Photo: Renato Ghiazza. Courtesy of the artist and Fondazione Merz. Courtesy Archivio Merz.

In more recent decades, Merz has primarily turned to drawing and painting. Presented in proximity to her woven surfaces, the drawings resonate with a similarly swirling, hair-breadth line. Still, the most arresting aspects of the show are Merz’s works in three dimensions. In a small inner room, viewers happen on a luminescent surface dotted with nine mounds of clay, variously rouged, gold-leafed and mottled. These are some of Merz’s Teste (heads)—unfired clay sculptures suggesting upturned heads craning skyward on elongated necks. Contained by a steel border, the milky and gently cracked surface is paraffin wax, repoured each time the work is exhibited.

For Merz, the candle wax is connected to the realm of the skies. She finds in its suppleness and near-translucence a sensation akin to the shifting quality of dawn. Here, again, she opts for the embodied poetics of transparency. The sentiment opens up from the bounds of the rectilinear wax surface and permeates the entire exhibition, offering an extensive—if overdue— space to inhabit her materially vivid domain. ❚

“Marisa Merz: The Sky Is a Great Space” was exhibited at the Met Breuer, New York, from January 24 to May 7, 2017, and at the Hammer Museum, Los Angeles, from June 4 to August 20, 2017.

Shannon Garden-Smith is an artist currently based in Guelph.