Marcel Dzama on Francis Picabia Shape-Shifting His Way through Art

Marcel Dzama, the Winnipeg-born, Brooklyn-based artist, cites Francis Picabia as his favourite artist. For Dzama, whose practice includes painting, drawing, sculpture, installation, performance, film, music, poetry and songwriting, the protean French artist Picabia is the ideal artistic ancestor. In addition to their common multivalent art making, they share a sense of play, an engagement with an eccentric erotics and a refusal to recognize traditional notions about what defines any art form.

Border Crossings asked Marcel to see “Francis Picabia: Femmes,” an exhibition of 28 paintings produced over three decades that was on exhibition at the Michael Werner Gallery in New York from September 5 to November 2, 2024. The following interview was conducted by phone to New York on November 4. Marcel Dzama’a most recent touring exhibition, “Ghosts of Canoe Lake,” opened at Winnipeg’s Plug In ICA on November 22, 2024, and runs until March 8, 2025.

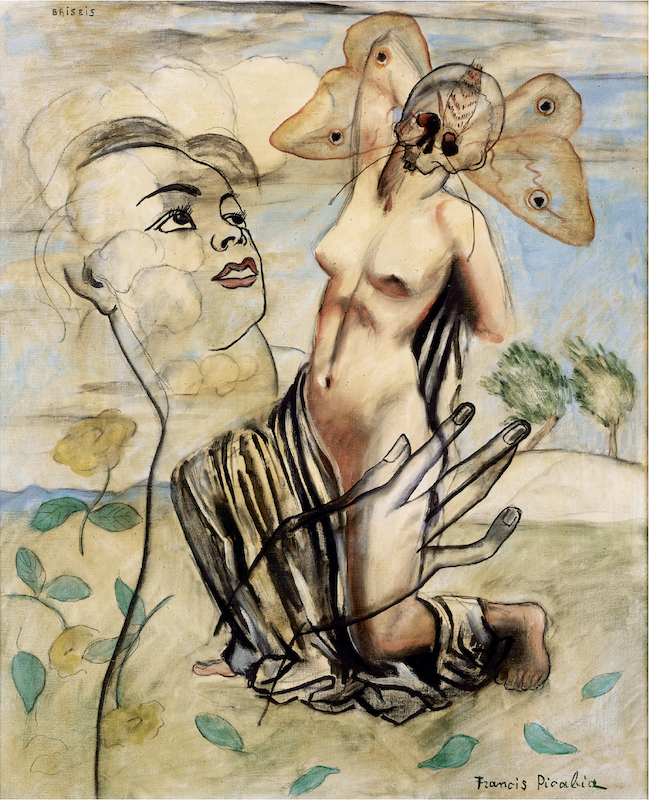

Francis Picabia, Briseis, c. 1929, oil, pencil on canvas, 73 × 60 centimetres. Courtesy Michael Werner Gallery, New York.

BORDER CROSSINGS: Do you remember when you first came across Picabia?

MARCEL DZAMA: It was through a BBC documentary about Dada called After the Rain. They had people re-enact moments in Dada, and one was Picabia reciting poetry. That was the first time I took note of his name. In that documentary they also talked about Duchamp and Picabia and Man Ray starting their own movement in the United States; at that point I was already obsessed with Duchamp. Actually, the first piece of Picabia’s I saw in person was in 2002. David Zwirner owned one of the 1940s paintings of a woman with a scarf around her head. It was in his summer house, and David had let my wife and me stay there for the summer. I remember being fascinated by this painting because it was at the head of a very long Franz West table. I spent the whole summer drawing with the painting straight above me.

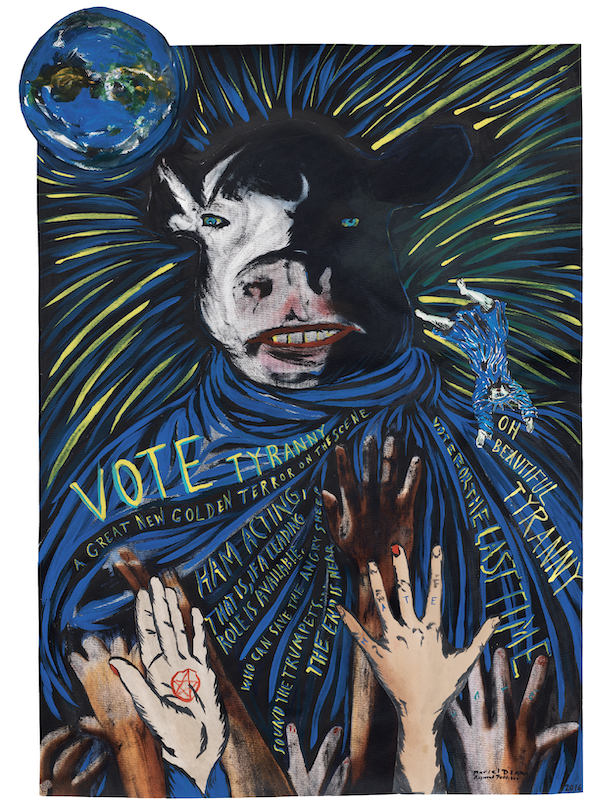

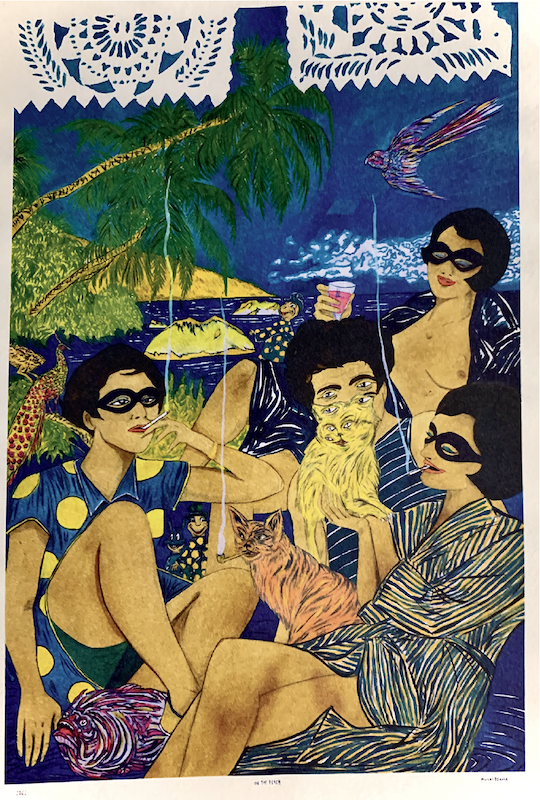

Marcel Dzama and Raymond Pettibon, Oh beautiful tyranny, 2016, ink, acrylic, oil and collage on canvas, 91.44 × 65.4 centimetres. © Marcel Dzama and Raymond Pettibon. Courtesy the artists and David Zwirner, New York.

What is it about Picabia that you find so interesting?

There’s a lot of tension in his work because, like Duchamp, Picabia was anti-art, but he also loved art. That tension comes across in the work. I really like the more vulgar paintings from the 1940s where he makes a copy of something and in doing that, he makes fun of it at the same time. There’s that whole prankster element to him, which I always enjoyed.

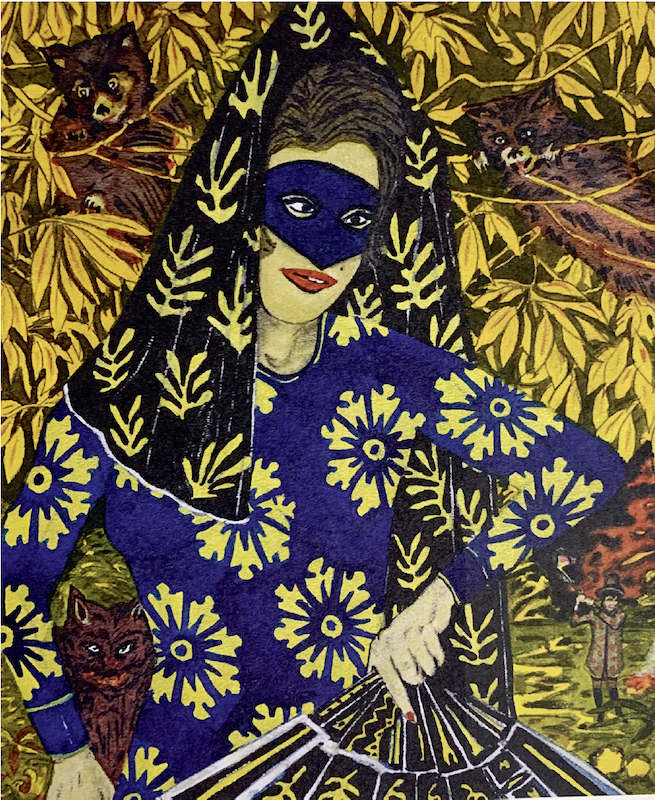

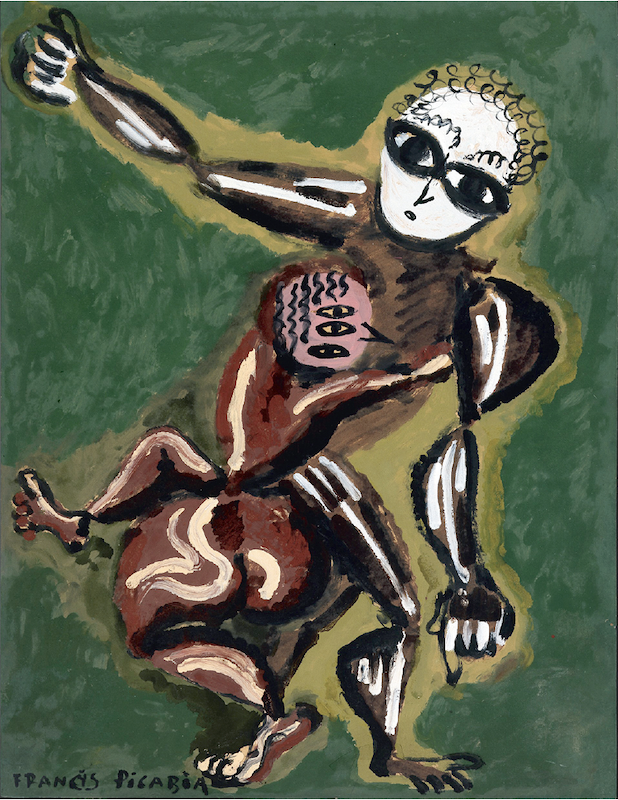

Francis Picabia, Masque, 1949, oil on canvas, 60 × 73 centimetres. Courtesy Michael Werner Gallery, New York.

What do you make of his drawings?

I love how loose and quirky they are, and the vulgar sexuality that runs throughout. There is a strange series of drawings of men, and some women, with giant penises. One, which is mischievously titled Le Classicisme, shows a urinating man who’s lifting the hair off the head of a kneeling woman, while she defecates and stares intently at the source of the black urine pooling on the floor. Behind them another woman with her arms upraised flees from the drawing like a refugee from a work by Picasso. Le Classicisme and a number of other drawings were published in 2018 in a Small Press Book edited by Stephanie LaCava with the title Francis Picabia: Litterature. It collects the nine covers and 17 drawings that Picabia had done in 1922 for André Breton’s literary magazine, Littérature. The text in the book includes excerpts from Picabia’s only novel, Caravansérail. I think Picabia’s drawings have even more freedom than the paintings, which is a lot, because compared with most artists there’s already so much freedom in the paintings. He was born quite wealthy and that allowed him to try whatever he wanted without worrying about any backlash to his income.

Marcel Dzama, So charming and disarming, 2022, watercolour paper, watercolour paints, pearlescent ink and pencil, approximate size 31.75 × 35.56 centimetres. Courtesy the artist.

Didn’t he own more than 120 automobiles over the course of his life?

Exactly. I was talking with Jason Rhoades at an opening at David Zwirner’s and he said his favourite thing about Picabia was his car collection.

The other artist who had tremendous freedom because of his independent wealth was Jacques Henri Lartigue. And Lartigue is tremendously playful, as is Picabia. How do you react to the sense of play that emerges in the work?

You could see he’s not worried about what other artists are doing, about what other art movements are doing, or about what’s going on around him. He’s in his own playful world, making works really to entertain himself. When artists do that, they often make their most interesting work.

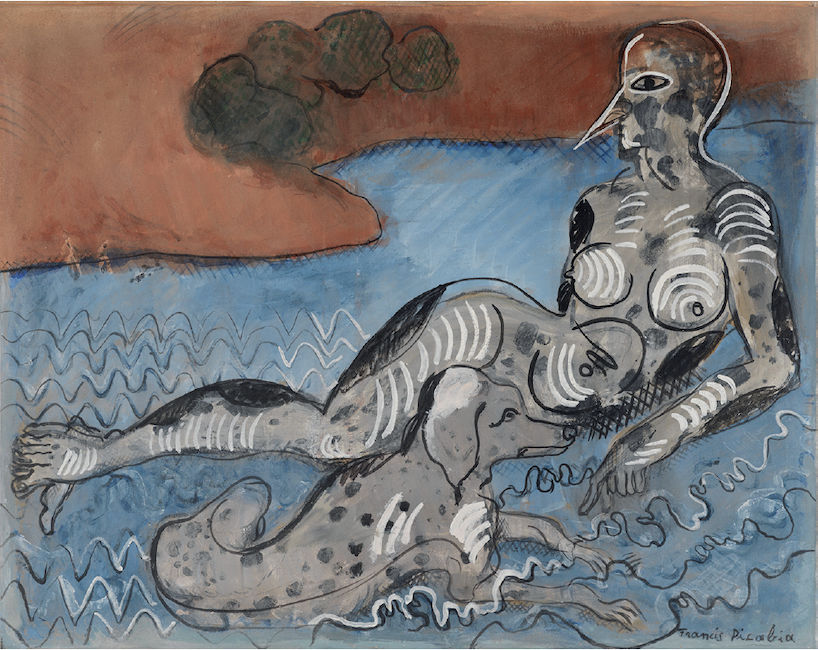

Francis Picabia, La femme au chien, c. 1925–1927, oil, gouache on board, 73 × 92 centimetres. Courtesy Michael Werner Gallery, New York.

David Salle says that his own kinship with Picabia is his reckless pursuit of whatever it was that interested him. Do you think of him as having a reckless quality?

When you look at the range of his work, you can see this interesting abandon in ideas. I guess that might make him seem quite reckless. The freedom that he claims is transferable to other artists, his recklessness is basically saying, if you want to make a drastic change, it’s there for you. You don’t have to dwell on it because you can always change again in your next series. I mean, he looked at two world wars and the speed of change from that period probably influenced him to make drastic changes in his own work. The reason he speaks so much to me is that I feel we’re in a time period where things are again drastically changing.

Marcel Dzama and Raymond Pettibon, No dictators, 2017, ink, acrylic and collage on canvas, 81.28 × 60.96 centimetres. © Marcel Dzama and Raymond Pettibon. Courtesy the artists and David Zwirner, New York.

You were at a symposium at MoMA in 2017 connected to the exhibition “Francis Picabia: Our Heads Are Round so Our Thoughts Can Change Direction,” and Peter Fischli, one of the artists on the panel, said that he wouldn’t be surprised if there were 10 different artists’ names assigned to the works in the exhibition and it was called a group show. Does Picabia have a style or is he all styles?

I feel at some point you can recognize his style, but the early steps he makes as he moves through abstraction, some version of impressionism and the mechanical paintings are drastic. They feel like they were made by entirely different artists from entirely different countries. But later you could see how the “Transparencies” paintings led into the grotesque nudes and the vulgar nudes. There seems to be some sort of flow that feels to me like the work of one artist. I was surprised by the number of works that were for sale in the Michael Werner exhibition. Picabia is an artist’s artist, and my guess is that collectors haven’t caught on yet. A lot of artists like his work: Mike Kelley was a huge fan; Raymond Pettibon and I talk a lot about Picabia, and we have collaborated on work about him. It seems like artists know about him, just not collectors.

Marcel Dzama, Sisters on the beach, 2022, watercolour paper, watercolour paint, pearlescent ink and pencil, approximate size 137.16 × 170.18 centimetres. Courtesy the artist.

What do you make of the “Transparencies” he made between 1927 and 1930? What’s going on in his imagination when he decides to layer images in the way he does?

It feels like he painted something first and then layered another one on top to see what the two images would make when put together. I see more of his playfulness in that, but in the transparency Briseis (1929), the placing of the butterfly right over the head of the nude seems to be coordinated. I think he definitely has control over the chaos that he is creating.

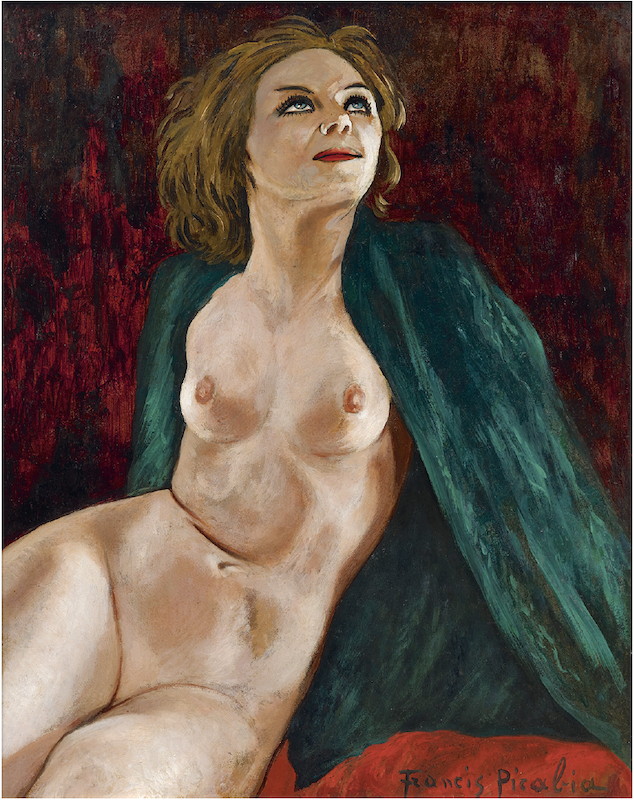

Francis Picabia, Woman in a Green Shawl, c. 1942–1943, oil, pencil on board mounted on canvas, 92 × 73 centimetres. Courtesy Michael Werner Gallery, New York.

The show at Michael Werner’s is called “Women.” How do you read the many kinds of women who appear in the show?

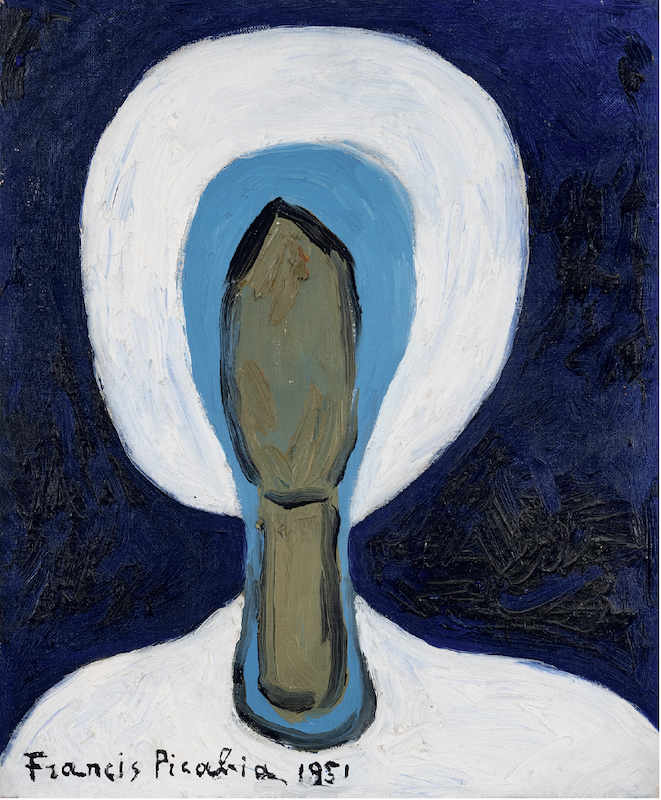

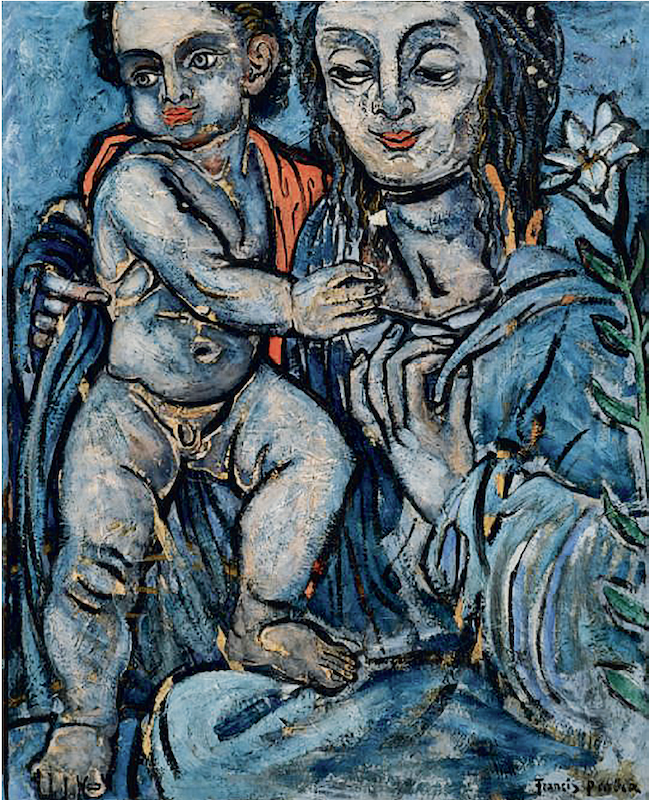

The kitschiness almost feels like a precursor to the way Andy Warhol would use his images of women. Picabia had a painterly way of taking away from the beauty of the image that he was using. I think he turns a lot of them into characters who have a story behind them. They have weathered a little bit. Then there is a painting like Dimanche (1951). The source material was this strange portrait of Mary in some chapel where she had this elongated face and weird hood, but he turned her into a candle or a light bulb. Then he paints what seems like a stereotypical Mary and Jesus portrait in Maternité bleue (1936–38) but with a spin that has a stained-glass quality. I don’t know what he was working from, but what’s interesting is the way Mary glances towards Jesus and the way she’s grabbing her own collar. You can’t ignore Picabia’s hand gestures. The way that his women hold their glass with their pinky up is very 1920s.

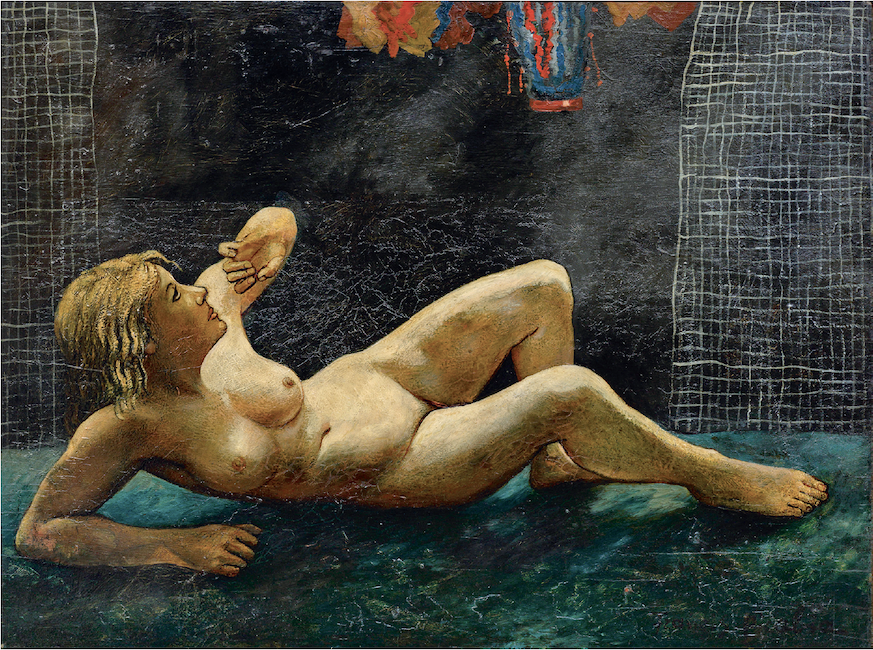

Francis Picabia, Untitled (Venus and Adonis), c. 1925–1927, oil on wood, 104.5 × 74.5 centimetres. Courtesy Michael Werner Gallery, New York.

The brown-haired woman wearing a green shawl in Femme au châle vert (1942–43) has a crease at her waist that is not particularly flattering. He makes no attempts to stylize the body or make it conventionally beautiful. Does he go with what he finds in his magazine sources, or does he adjust the image to look the way he wants it to?

I feel like he’s making the image look that way. That one is my favourite painting in the show; the look in her eyes and her smirk make her a cartoon image of a portrait. There’s also a crazy smile on the face of the woman in Masque (1949). You can see that he painted out some character next to her, and as evidence for that former presence Picabia conspicuously leaves in an ear. It’s surrounded by red and white star-like flowers set on a blue-sky background. And then the light on the woman’s face is so sinister.

Francis Picabia, Untitled, c. 1937–1940, oil on wood, 96 × 128 centimetres. Courtesy Michael Werner Gallery, New York.

There is a line in I Am a Beautiful Monster where he says, “I would write books of mad tenderness.” Do you think that his paintings also have that quality of mad tenderness?

Yes. Maybe that’s what it is. Instead of objectifying the nude women from the magazines he is using, he adds this madness to the process.

Marcel Dzama, self-portrait with artwork Drawing on a revolution, mural painting located in Spain at La Casa Encendida, Madrid, acrylic paint, approximate size 4.57 × 6.1 metres. Courtesy the artist.

Was your first borrowing from Picabia when you took the polka dot costumes from his ballet Relâche (1924), which he made with Erik Satie?

I did the polka dots because I had these characters who looked too much like terrorists, and I didn’t like that association—this was around the time of 9/11. I wanted to make them more playful, so I thought of the polka dots from Picabia. I made them more like Harlequin characters, so instead of being an embodiment of terror, they were like pranksters. Then I drew the human/animal creature from The Minotaur or The Dictator (1937), Erwin Blumenfeld’s black and white photograph. In Picabia’s painting called The Adoration of the Calf (1941–42), he copied directly from the photograph, but he added some hands at the bottom in what was a fascist salute. This was around and during World War II, so both were making reference to a fascist dictator.

Marcel Dzama, still shot, Death disco dance, 2011, video projection, 27 monitors, 4-minute loop. Courtesy the artist.

What was it about that image that you found so compelling?

I liked that metamorphosis of creatures and people, and it was very timely during the first Trump years. I even made a protest poster of it that said, “No Dictators,” and took it to a couple of marches. Then in 2013 I made a film called Une danse des bouffons (A jester’s dance). It was loosely about Marcel Duchamp’s love affair with Maria Martins, the Brazilian sculptor who was the model for the figure in Étant donnés, and in the course of the story in the film, Duchamp is reborn. The opening for that rebirth is a vagina at the centre of the calf creature’s body. There’s admittedly a little Cronenberg influence there, too. In being reborn, Duchamp renews his passion for art as a full-bodied human.

Francis Picabia, Dimanche, 1951, oil on canvas, 46 × 38 centimetres. Courtesy Michael Werner Gallery, New York.

Your film combines references to both Duchamp and Picabia. Étant donnés is an uncomfortable image. Is there anything equivalent in Picabia?

The Adoration of the Calf was the most frightening image he made and it’s my favourite. There’s also a clown image called Le Clown Fratellini that was made around the same time, and there is the Hanging Pierrot (1940–41). But that calf head found its way back into my art. I was asked to be in Jay-Z’s performance art film for the song called “Picasso Baby.” I didn’t really want my face to be in a music video because that wouldn’t be interesting to anyone. So for the “Picasso Baby” video I dressed as Picabia’s painting of the calf. For “Picasso” I was representing Picabia.

Francis Picabia, Maternité bleue, 1936–1938, oil on canvas, 102 × 83 centimetres. Courtesy Michael Werner Gallery, New York.

During the MoMA panel Peter Fischli described what Picabia was doing as “positive nihilism.”

That’s perfect. If nothing has meaning, then it’s easy to shape-shift your way through it.❚