Marc Séguin

The wolf is out.

Marc Séguin’s take-no-prisoners, in-your-face figurative Roadkill paintings have a potent, aura-laden resonance that extends considerably beyond the outsized expanses of their canvas grounds. In the haunting oil paintings exhibited here, the wolf is out, loping, lunging and rending human flesh. The presumptive blood from these encounters runs free on the brink of the abyss.

Séguin is arguably one of only a bare handful of painters now working who effectively shows us that desire, as epitomized by Goethe’s Faust, has to be held in check or all hell breaks loose. The core subject of his work is binary: the issue of painting itself, always subject to a reductive spirit as liberating as it is tonic, and the issue of representation, which is here a semiologist’s darkest fantasy of what happens when desire exceeds all known limits. In fact, Séguin’s painting techniques have always hewed to a reductive impulse, a minimalist, formal undertow, which makes his work all the more powerful and unsettling, even, at times, unassimilable. Séguin is a tremendous savant when it comes to unleashing the full, unbridled power of the image, with the leanest economy of means.

He has always been driven to show us our demons, whether in animal or human clothing and not at the level of the illustrative, however graphic the portrayal— but in terms of the demonology of the popular culture and the phantasms of murderous interiority that clot every human heart. It is no surprise to learn that he collects old grimoires and black magic tracts and has a formidable library of such.

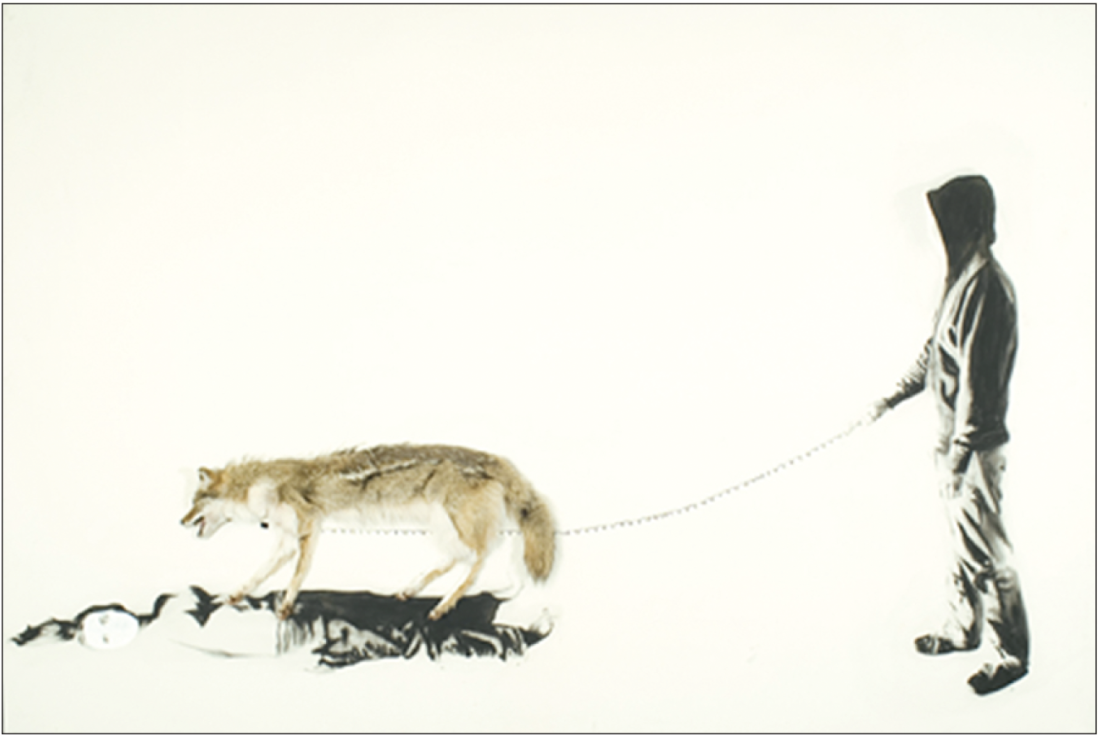

His pictorial space is at once bluntly literal and oneiric, and the reconciliation of this duality is one the viewer readily understands because the work obliterates all protracted narrative readings in the virtual instantaneity of its impact. The literal stems from the fact that the road kill in the series’ title is actually stitched onto the canvas ground and finds its perfect dialogical partner in the painted figures. Perhaps some of the frisson that raises the hair on the nape of your neck as you try and come to terms with this remarkable work owes to that fact. Because the space around the figures is mostly blank, abstract, it acts as a magnetic vacuum for the eye to hone in on the adjacent, always unsettling images. It effectively focuses our attention on the representational vignette, and the horror of the encounter is magnified.

Marc Séguin, Bitches 2, 2007, oil and coyote on canvas, 9’ x 13’ 3”. Courtesy Corkin Gallery, Toronto.

The virtuosity of Séguin’s paintings stems from his employment and subversion of traditional artistic methods—his uncanny skill at rendering the figure, on the one hand, and his importing taxidermy into oil painting, on the other. Their effect, what Walter Benjamin knowingly called (in his On Hashish) “Umzirkung”— which seems to be painted along with his figures in relation to the integrated road kill— stakes a tenacious claim on the viewer that is hard to shake off.

There is a lovely and never slavish echo of Philip Guston’s late great dead-end world here, with its hooded KKK denizens and their unfettered nooses, and we remember Betty Goodwin’s traumatic universe, too, with its ubiquitous tendrils and death demons running amok. The spectral and the literal co-exist in this painting world, fraught with emotional registers and nightmare scenarios and with unerring proximate grace.

Here is an unlikely cross between Sergei Prokofiev’s Peter and the Wolf and Joseph Beuys’s seminal performance piece Coyote: I Like America and America Likes Me, 1974, in which Beuys, wrapped in felt, shared the René Block Gallery space with a coyote for several days. Séguin himself says that this series references Beuys, albeit “in a strange way.” The wolf and coyote paintings segue with his move to NYC (Brooklyn) and the series title is, after Beuys or perhaps in homage to him, “I Love America and America Loves Me.” While the coyote symbolized for Beuys the most primitive incarnation of America, it seems to have a similar resonance for Séguin.

Beyond the relevance of Beuys’s performance and the sacred status of the coyote, the wolf in Séguin’s paintings incarnates the archetype of which analytical psychology speaks so eloquently. Indeed, the wolf here is the living incarnation of what analytical psychologist Edgar Herzog once called the “death demon” archetype.

Marc Séguin, Self- Portrait with Veuve Clicquot no. 1, 2008, oil on canvas, 36 x 48”. Courtesy Corkin Gallery, Toronto.

In Séguin’s dark paintings, we are confronted with a malevolent entity that surges up from the unconscious with sharp claws and teeth, eager to devour both the living and the dead. Here, it sees the light of day and, like an End of Days obscenity—Séguin seems to imply—harvests human flesh.

Indeed, we are tempted to ask of the “victims” in Séguin’s paintings what the protagonists of Betty Goodwin’s figuration also forced us to question: are they asleep, dreaming? Or are they incarnate souls suffering all the torments of the damned?

Séguin incarnates his wolf-bogeyman as a protest against the surfeit of our consumer culture— more telling still, as felt counterpoint to the wanton excess and hypocrisy of the condition of being here in a terrorism-threatened, endlessly war-torn world. He seems to be saying: I will show you the demon that lies dormant within you. I will show you what you truly fear.

Séguin’s figuration broaches abstraction the way Jean-Paul Riopelle’s abstraction always broached figuration. Riopelle, like Harold Klunder, too, was always held to be one of the finest abstract painters this country has produced. Both asserted they were figurative painters. Marc Séguin paints the figure, but invokes and evokes registers of meaning that lie below, above or beyond the ground plane of representation. He wills into existence the no man’s land beyond any moral compass, where the harrowing begins and the verities of our existence are overturned and rendered mute. ■

“Marc Séguin: Roadkill” was exhibited at Corkin Gallery in Toronto from May 3 to July 13, 2008.

James D. Campbell is a writer and curator in Montreal.