“Maps in Doubt”

In the good old days of postmodernist thought, Jean Baudrillard recalled in “The Precession of Simulacra,” an essay in his book Simulacra and Simulation, an allegory written by Jorge Luis Borges that imagined “a Map of the Empire whose size was that of the Empire, coinciding point for point with it.” Baudrillard’s argument is that the map, both in this parable and present experience, precedes real space and that political powers strive to make lived existence reflect simulation. His famous “deserts of the real” are vestigial spaces that no longer reflect simulacra—of maps or other proxies for actuality.

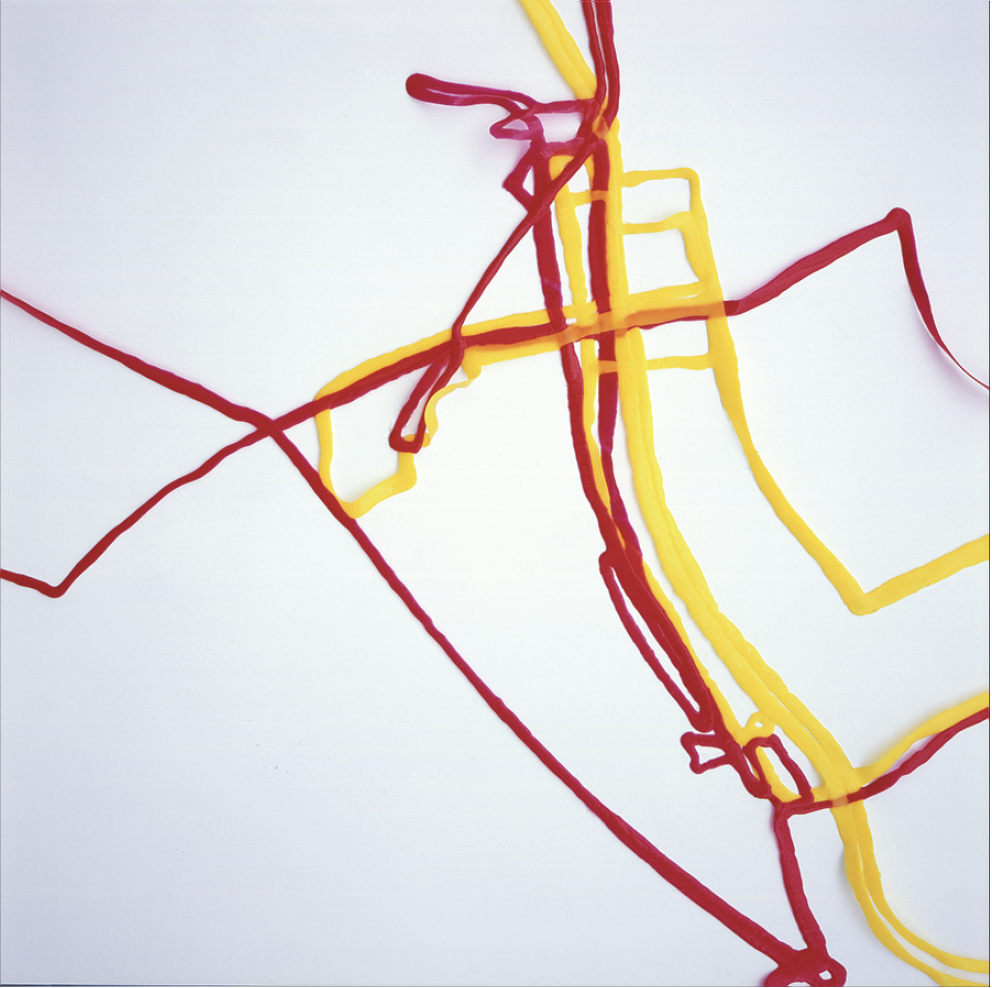

Gwen MacGregor and Sandra Rechico, Floppy Map (Montreal), 2008, detail, silicone, 14 x 14’. Photo: Miles Stemp. Courtesy the artists.

Mercer Union: A Centre for Contemporary Art is newly located in such a Torontonian desert, in a working-class, immigrant neighbourhood named after the unappealing Dufferin Mall. The former community theatre has a gritty shell, but inside, it sports white-box galleries. This location boasts a new cluster of galleries and arts organizations; with more momentum these will engender gentrification and put the area back on the map. I’ll propose a trendy name—NoDuffMArt.

It’s fitting, then, that one of the inaugural exhibitions for this space is Gwen MacGregor and Sandra Rechico’s collaborative installation, “Maps in Doubt,” that shows the inadequacies of objective (and simulacral) maps for describing experience. This exhibition’s works stem from data collected by each of the artists. Rechico is an analogue recorder, writing tedious details about her travels in a notebook; MacGregor’s moves are plotted automatically by a digital GPS system. Examples of this collected, digitized and printed system comprise Data (Münster), 2008. In the show’s other works, similar information is compared in visual representations that summarize their journeys.

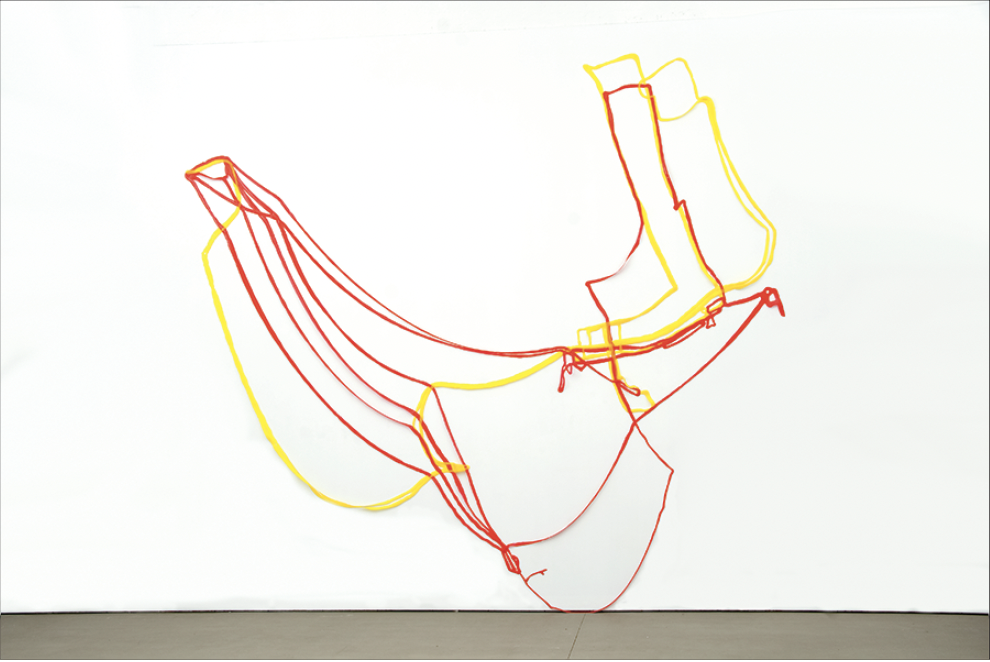

Gwen MacGregor and Sandra Rechico, Floppy Map (Montreal), 2008, silicone, 14 x 14’. Photo: Miles Stemp. Courtesy the artists.

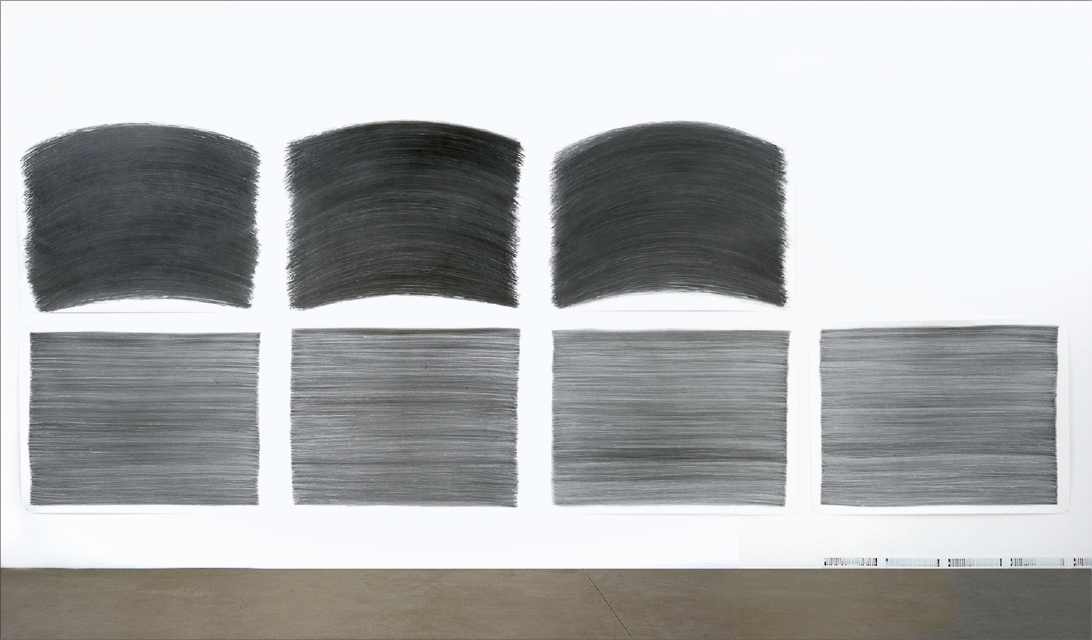

Distance (Kassel), 2008, is the simplest of the mapping enterprises insofar as only total distances are represented; the execution, though, is exceedingly laboured. Graphite strokes make manifest the distances travelled by each artist; Rechico presents three leafs of approximately metre-wide paper, and MacGregor four. The tens of thousands of linear marks represent the astounding 69.05 kilometres and 82 kilometres traversed by each artist. These are installed in a comparative grid that shows independent solutions for the task; Rechico makes curved lines that suggest the arc of the artist’s arm and her analogue approach. MacGregor’s lines are more or less straight; and ultimately might offer a more precise measure, given that Rechico’s curves add several erroneous centimetres to each page-wide stroke and many metres to the total distance. Each horizontal stroke suggests a stride, a basic unit of human movement, recalling Robert Morris’s Blind Time drawings (1973–2000) that also show the body’s range, even though MacGregor and Rechico’s trips may have been made by foot, train, bus or other modes.

Another cartograph of incredulity is the painterly Floppy Map (Montreal), 2008, that hangs from the wall. MacGregor traces her whereabouts in bright red and Rechico in yellow silicone lines that evoke the graphics of subway system maps. The blobby swaths twist in space as a reminder that Cartesian plotting is an abstraction; the third dimension dutifully plotted as elevation by MacGregor’s GPS (some hilariously erroneous data locate MacGregor at millions of metres above sea level) are eliminated. Sagging like a Claes Oldenburg sculpture, the maps become fleshy, all too human, and prone to error. Indeed, MacGregor points out that her GPS doesn’t work in the subway, so her recorded plots may bend space and reason. Rechico notes that she is careful but that it’s all too easy to make mistakes while constantly recording.

Gwen MacGregor and Sandra Rechico, Distance (Kassel), 2008, graphite on paper, 24 x 9’. Photo: Miles Stemp. Courtesy the artists.

The artists play with arbitrary analysis in Working Days (Toronto), 2008. Again they use a matrix, this time composed of letter-sized Lambda prints tracing the independent movements of the artists around Toronto. Each column shows a data-form-of-the-month. November 2007 shows simple, plotted points; January 2008 applies a Voronoi diagram; and April yields the total area travelled, juxtaposed (in winsomely paranoiac fashion) along with the sites from 2007 of known marijuana growth operatives. The graphics serve a futile self-surveillance—much number crunching and exotic graphing reveal almost nothing about the movements of these two artists except perhaps that they frequent similar parts of the city. What remains is the official nature of the data’s presentation. Working Days takes aim at the seductive charts and diagrams of urban-planning presentations, social metrics and epidemic models that can seem compelling even if their data are flawed, presumed or absurd.

The duo are careful to note that the travels they record are chosen because they are related to art-career activities, whether visiting Documenta 12 in Kassel, installing an exhibition in Montreal or going about the quotidian business of art making and working in Toronto. Rechico and Mac- Gregor unpack ideas fostered by Duchamp, Rosenberg, Kaprow, and many others, that art and the artist’s life are intertwined in creative performance. But is everything an artist does necessarily artful? These journeys tell of a historical situation in which art is made within a process of international networking and idea exchange. The decentredness of the present art world that becomes manifested in international art fairs, biennials and art tourism is also connoted by these dubious maps. To be a player in the art market is to bounce from Miami to London to Venice to Beijing and so forth; the scope of a star artist or curator’s travel has become a marker of importance (Cai Guo-Qiang’s globetrotting is a spectacle in itself). MacGregor and Rechico set forth a frustrated set of maps in media and conceptual tropes that are to be read as overtly artistic. The selfconsciously flawed works equate journeys as performance, but with travels that are synecdoches of careers, this duo offers a critique of a professional artless precession that inadequately stands in for the artist and her expression. ❚

“Maps in Doubt,” curated by Dan Adler, was exhibited at the new Mercer Union: A Centre for Contemporary Art, Toronto, from October 24 to November 29, 2008.

William Ganis is a professor of art history and gallery director at Wells College, New York.