Magic Carpeting

The Druze artist Fatma Shanan has carpeted the world. Or less ambitiously, she has made a world for herself out of the carpet. Her strategy for the last decade has been to find a way to make the carpet a metonym for her own body and being. A common and revered domestic object, the carpet has been dislocated from its conventional context and made into a vehicle for introducing the tension among individual identity, the difficulty of achieving it and the necessary collective identity in Druze and Israeli culture. “I painted the carpet,” Shanan says, “to ask questions about my own identity in my community and in the world. It starts from biography and from there goes to a bigger, universal place.”

In 2009 she began using her own face in a series of self-portraits; then she expanded her subjects: “I painted portraits that were the whole bodies of other girls, but I painted girls who looked like me, so in a way I was painting myself.” The range of her self-portraiture included a painting in which she was inside the pattern of a carpet. This work combined a pair that was to become her preoccupation: the carpet and the female body. Shanan has said that the carpet is “not an object but a living thing,” and that attitude has given her permission to paint it in unusual situations (her paintings are based on her own photographs). In Maya #1, 2014, a young woman stands under a magisterial tree in an otherwise open landscape. The painting is a study in harmonious colour and shading; standing on a carpet, she blends into the tree trunk behind her and the carpet blends into the earth on which it sits.

Fatma Shanan, Carpets on Asphalt, 2015, oil on canvas, 120 x 180 centimetres. Photo: Elie Posner. © The Israel Museum, Jerusalem. Courtesy the Israel Museum, Jerusalem.

The carpet has turned out to become an extremely versatile subject. In Road #1, 2014, she places them in a configuration three deep and 15 long, on a rooftop in Julis, the village in northern Israel where she was born and lives; in Carpets on Asphalt, 2015, she arranges nine carpets on asphalt as a way of setting up textural and colour contrasts; and in Untitled, 2016, she shifts her perspective to an aerial view as a way of emphasizing pattern and presenting the paintings as abstractions. Throughout these works you can see the connections she is making to previous styles of representation, from the decorative intensity of Gustav Klimt to Pre- Raphaelite detailing, where every inch of the surface is packed with incident, and to a style of dry brush paint application used by Michaël Borremans, her favourite painter.

Shanan is aware that using the carpet connects her to a tradition of representation that has its own problematic history. She has read Edward Said on Orientalism and knows that the most infamous pairing of a woman and a carpet is Cleopatra and her unrolling in the presence of Caesar. While she accepts the sexualized body revealed through this narrative, her interests are in pushing where an investigation into the body can lead her. In the last year she has been expanding the contexts in which she places her own body. She frames the inquiry through Jean-François Lyotard, who “asks the question of how, and if, thoughts can continue on without the body. It’s a metaphor for the question of the relationship between mental and physical restrictions because there is a connection between the mental effect that physical restrictions have on us, on our biology and even on the body’s language.”

Self Portrait on Parquet, 2019, oil on canvas, 60 x 45 centimetres. Photo: Jens Ziehe. © Fatma Shanan. Courtesy Dittrich & Schlechtriem, Berlin, Germany.

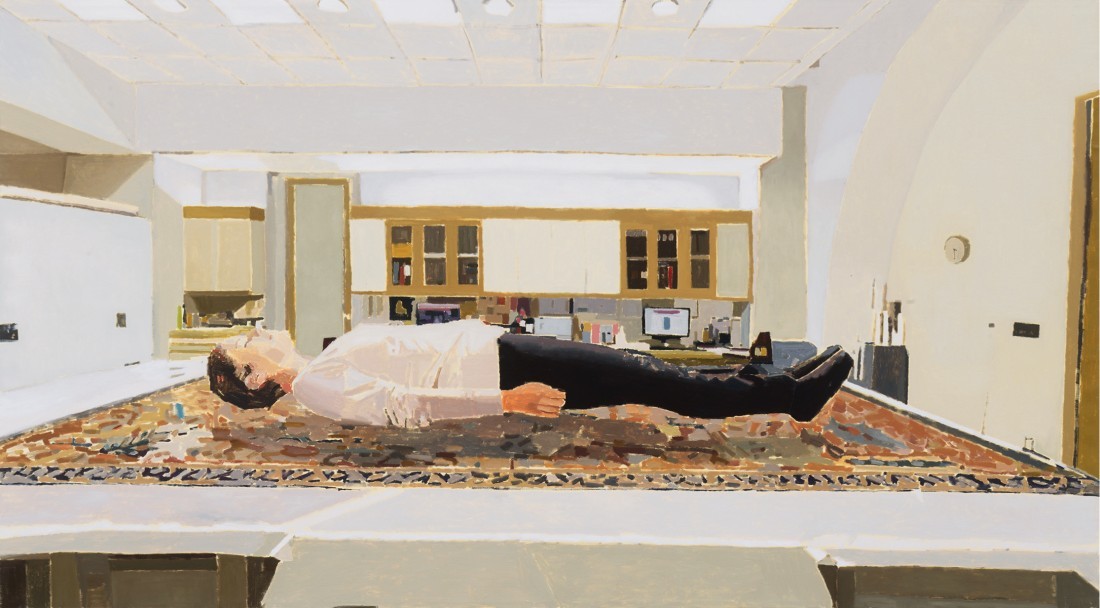

In the same way that she has generally resisted depicting the body as other artists have done, she was concerned to shift the way her own body could be read in places outside of Julis. Each time she travels to a residency, she uses the occasion to re-place her physical being in a new context, like the Metropolitan Museum in New York, where her research into their carpet collection resulted in Floating Self Portrait, 2019. The painting shows her body hovering above the table on which a carpet sits for examination. The restrictions the museum placed on the distance she had to maintain between her and the carpet meant that she had to move in unfamiliar ways: “I had to stretch my body and my neck in order to take the photo and so the carpet is like a magnetic field.”

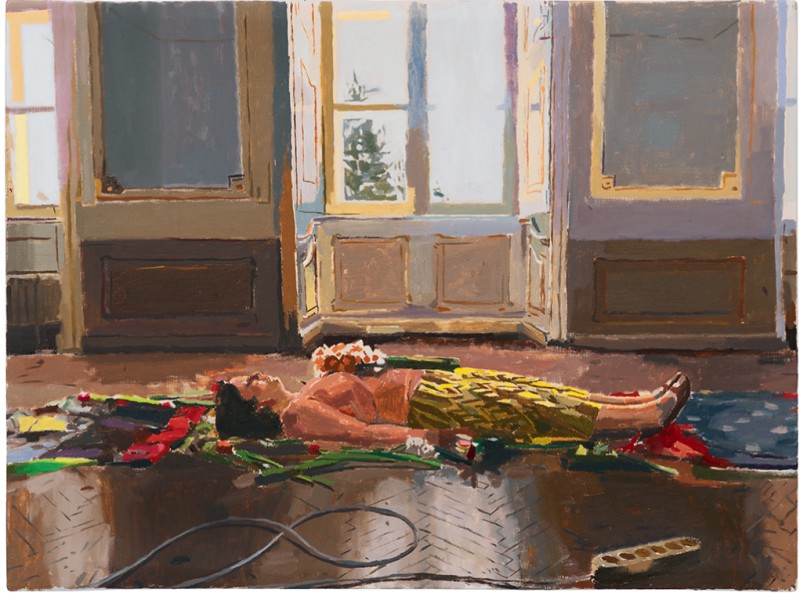

Shanan is aware that she is engaged in a self-performance, in which the audience is deferred until the painted evidence of the event turns up as a painting on the wall of a gallery. In Romania, working in an 18th-century baroque palace converted to an art gallery, she recognized she needed to change the tone of her presentation: “Historically, the baroque is a distant period, so I wanted to create the feeling that I am there but it is far from me.”

Floating Self-Portrait, 2019, oil on canvas, 111.5 x 200 centimetres. Photo: Jens Ziehe. © Fatma Shanan. Courtesy Dittrich & Schlechtriem, Berlin, Germany.

Shanan’s paintings are suggestive because her subjects enter occupied territory. Whenever she presents a supine, sleeping woman, she moves into the land of the fairy tale where women are waiting to be awakened through some external intervention. But Shanan’s figures are never in a coma or in a state of suspended consciousness. She says, “I am influenced by Marina Abramovic´ and other video artists who use their body to talk about agency but I am doing that through the painting.”

Yellow Skirt and Pink Flower, 2019, articulates the various ways her representations can be understood. The painting reveals the delicate contour of the figure’s waist as well as a pair of powerful hands with dark green painted fingernails, a compelling combination of the sensuous and the physical. While she says it was unintentional, the stalk of the pink flower is close to the green of the Druze flag. The woman who wears the yellow skirt and holds the pink flower is the embodiment of the complicated identity Fatma Shanan has been painting for more than a decade, an identity that touches on aesthetics, gender, politics and power. ❚