Lynne Marsh

This exhibition, “Lynne Marsh,” brought together three strong video installations by the artist. Camera Opera, 2008, Stadium, 2008, and the earlier Ballroom, 2004. All represent a seeming departure for Marsh, at the same time comprising a very convincing testimonial to the topicality and importance of her practice. While she is working here with real spaces, she has not entirely eschewed the fictional virtual spaces she worked with in the past. Instead, she has created hybrid spaces that function as telematic fictions for a viewer who becomes less a voyeur and more a complicit player in the making of meaning.

These works thematically explore theatricality and the temporal, the tremulous private body, and the real/corporeal public performer/author in the context of specific architectural environments that at once reify and codify both lived corporeal events and fictional epiphanies. In terms of our immediate lived experience, I experienced a genuine frisson as I moved or sat in front of these works. While I felt I was at the centre of the matrix, I also understood that the artist’s own body was the linchpin. As a necessary sequel to that there was the adumbrated space of reflection, which all these works finally segued into. Given the magnetism these videos exerted, it might be appropriate to invoke the name of Franz Anton Mesmer here, but Lynne Marsh is not an operator set upon putting her “patients” into a crisis. Instead, she is intent on allowing her viewers to appraise and savour the poetic stakes in the project of videography itself and how she has upped the ante. If it seems that she owes more to the German philosopher Jürgen Habermas than to Mesmer, her own concept of communicative action has a decidedly feminist cast. And, it could be suggested that Marsh is less indebted to either than she is videographic heir to Hedy Lamarr, the illustrious Austrian-born, American actress and inventor.

Lynne Marsh, Ballroom, 2004, looped video projection, sound. Photos courtesy the Musée d’art contemporain de Montreal and the artist.

Entering the spaces in which her works are installed, the viewer is confronted by Ballroom first, then Camera Opera and, finally, Stadium. But the latter is arguably the fulcrum for all three and is a bravura work of videography by any standard. Here the viewer is met as much by the theory of Habermas as by the spectre of German cineaste Leni Riefenstahl, director of the notorious Triumph of the Will, a propaganda film that documented the 1934 Nazi Party Congress in Nuremberg. Jürgen Habermas employed his concept of communicative action to name “agency” in the form of communication. In other words, he embraced the free exchange of beliefs and intentions under the rubric of a wholesale absence of domination. Communicative action becomes more precisely dramaturgical action in the work of Lynne Marsh, but in many respects it still falls under the umbrellas of the epistemologies of seeing and the ethics of making and can be applied to politics, the phenomenology of the social world—and radical works of art. The underpinnings of communicative action presume that human agents are free to adopt one another’s signature perspectives and can thus take actions that will have just consequences for everyone. As a videographer in this respect, Marsh is a democratic savant without equal.

Her video works—while ostensibly starting with herself in the first person, not only as author but as enabling agent in real time, and with her own body image in space as transformative agent first and foremost in the mise-en-scène— are radically open to, and actively contingent upon, our participation. They are hardly hostage to theory, even as they work from and resonate within it.

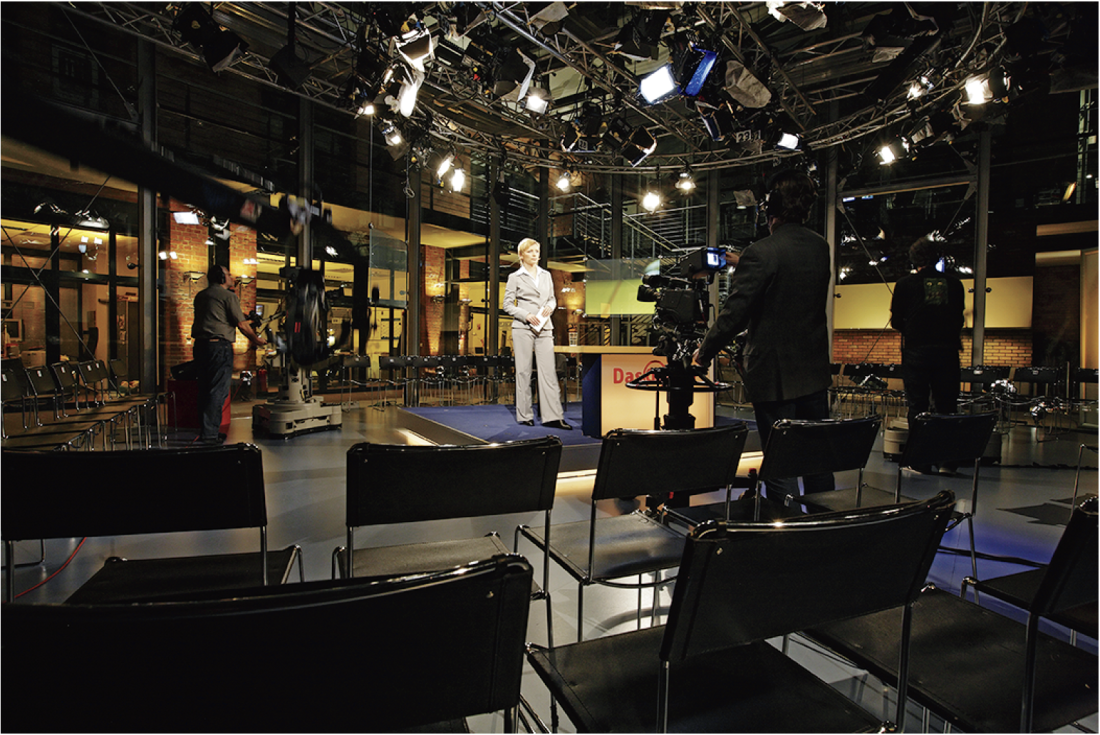

Lynne Marsh, Camera Opera, 2008, two-channel video installation, sound. Photo: Hans-Georg Gaul.

The videos shift the constitutive onus to us as viewers and we are changed as a result. It is not only the vulnerability of a communicative self (the author) that is at stake here, but the porosity of the audience who are implicated and empowered. While each of these works involves a single female figure who controls and changes the architecture through her movements or the movements of the camera at her command, it is not long before we recognize the essential truth: it is we, her viewers, who are drawn in and are subsequently instructed and exalted.

Stadium, 2008, is installed in a cinema-like setting with a few rows of severe wooden seats. Notably, it was executed in the Berlin Olympic Stadium where the controversial 1936 Games were held, and the work tracks the arc of an athlete hurtling through a seeming infinity of empty seats.

In the earlier, large-scale wall projection entitled Ballroom, 2004—a rapturous marriage of an opulent Parisian music hall scene à la Folies Bergère and a Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus performance—it was impossible to look away from what seemed a very perilous, but altogether magnetic, high-wire act. In fact, we were rapt witnesses to the spectacle of the artist herself in glamorous attire, suspended upside down, arms outstretched, twirling like a proverbial top in the upper quadrants of London’s Rivoli Ballroom, while the soundtrack seamlessly paced the proceedings, accentuating the acceleration of the artist’s spinning body. Here was a conjuring act, but there was no doubt that what we were seeing was real. Videogame heroine Lara Croft in a ballroom fantasia with her limbs akimbo, encased in the architectonics like a proverbial pearl in an oyster setting, or a fly in amber, and just as sumptuous and luminous. Was this the reality or the Baudrillardian simulacrum? It was, in fact, both.

Lynne Marsh, installation view. Photo: Richard-Max Tremblay.

Last, in Camera Opera, presented on free-standing monitors on tripods, the audience moved freely within their ambit and became surrogates for the artist herself, instigating the action. The video circumscribes an anchorwoman in a CNN-like TV studio just moments before airtime, but it is the roaming perspective of the cameras themselves that becomes the primary focus. Behind the cameras, it is the viewer morphed into Marsh’s own shoes in this fictional space, transformed into interlopers and voyeurs, but also behind-the-scenes optic technicians, invisible but unavoidably present, because it is, in fact, our ambulatory selves who are complicit with the “director” and ready to give the anchorwoman her cues at a moment’s notice.

The videos of Lynne Marsh are about communicative action at its most enlightened, most enthralling, most fraught. Yet we are reminded that the Achilles heel of Habermas’s theory was its dubious positioning on matters of gender. Lynne Marsh, a gifted videographer who uses the principles of a communicative model without the androcentric tendencies of Habermas, effectively overhauls his notion of praxis. Marsh’s works certainly celebrate the hopes, dreams, aspirations and expectations of contemporary women and, if they have been speciously called extra-human, they also argue powerfully against the perils and follies of a specifically phallocentric gender-structured notion of the world.

All three installations offer a full array of theoretical implications, but they are also extra-theoretical. These videos cast a spell on the beholder and engage us in a concept of communicative action as compelling as it is exacting. ❚

“Lynne Marsh” was exhibited at the Musée d’art contemporain de Montreal from November 6, 2008, to February 8, 2009.

James D Campbell is a writer and curator in Montreal who contributes regularly to Border Crossings.