Lygia Pape

On the tiles of the eaves of the

homes grew

grass greener than hope

(or the fire

of your eyes)

It was life exploding through all

the city’s cracks

in the shadows of the war

—Ferreira Gullar, Dirty Poem

The Brazilian critic Mário Pedrosa wrote in 1979 that of all the artists in Brazil, “none is richer in ideas than Lygia Pape.” Under the grid of cast concrete ceilings at the Met Breuer in New York, the products of Pape’s ideas continue to bewitch. Clean lines, smooth squares and uncluttered cubes shape her early minimal work. Then, corners are folded and surfaces are peeled back, or cut into, to create intricate shadow play. Haunting boxes made under military dictatorship reveal an ant collection and a cockroachfilled case. In one video, cubes on a beach hold artists and poets ready to break out playing samba music. Her first retrospective in the US, “A Multitude of Forms,” reveals Pape’s spirit of resilient freedom, and what Pedrosa referred to as her “sinewy inspiration.”

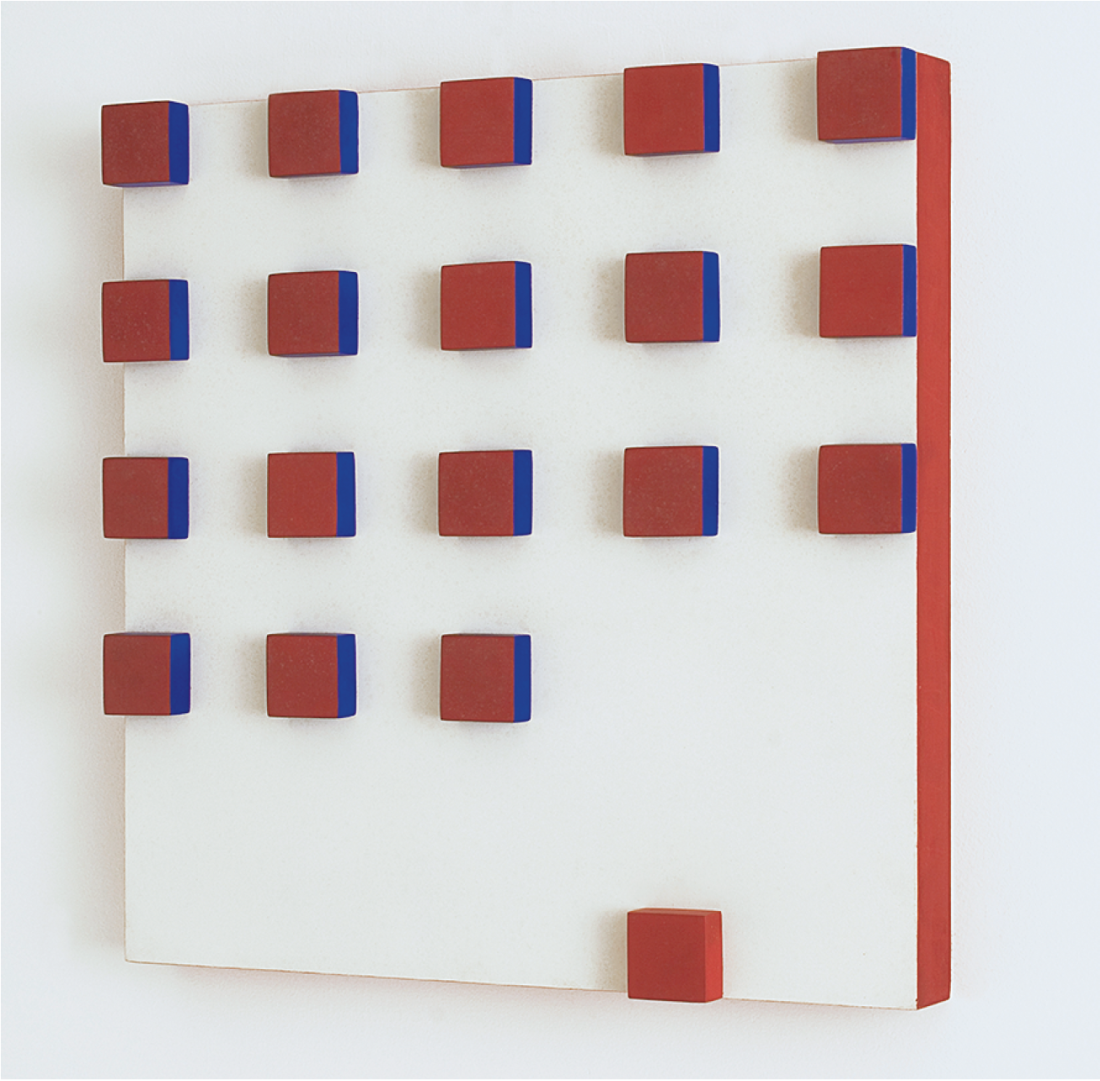

Born in 1927, Pape had no early training in fine art. At 22, she married Gunther Pape, a chemist of German descent, and the two moved to Rio de Janeiro. She soon met Décio Vieira, Ivan Serpa, Lygia Clark and Hélio Oiticica, and together they formed the Concrete Art collective Grupo Frente in 1954. It was three years after the first international biennial was held in São Paulo, and though the members of Grupo Frente kept a weather eye on Europe, they aimed to form a Brazilian movement. Utilizing simple geometric shapes and primary colours, they sought to create new forms within limited parameters and to “teach viewers to exercise their senses.” Though Pape later confessed she never particularly enjoyed painting on a flat surface, her early works masterfully echo Kazimir Malevich’s taut suprematist compositions. At the Breuer, these are paired with a series of reliefs. Pape created unframed fibreboard-on-wood rectangles in series that predate and predict Donald Judd’s famous boxes and stacks. Subtle studies in form and light, their shadows drift, depending on your line of sight.

Lygia Pape, Relevo (Relief), 1954–56, gouache and tempera on fibreboard on wood. Photo: Paula Pape. © Projeto Lygia Pape.

Rectilinear black and white drawings and woodcuts await in the second room. Pape called these Tecelares, or “weavings.” They are abstract celebrations of a traditional craft. Some are dense and inky, made up of perfectly parallel black lines, nearly identical to the “Black Series” Frank Stella would paint and gain renown for years later. Others are coated more thinly, carrying over creases from the wood that look like ripples in a muscle. Pape used razor-thin incisions to disrupt and warp the organic direction of the wood grain. Her work across mediums is an exercise in setting narrow restraints and pushing hard and intricately against their limits.

In the exhibition’s third gallery, Lygia Pape’s geometrical forms come to life. A video shows white cylinders and orange rectangular boxes gliding across a black stage. With the magnetic energy of dancers, eight wooden shapes arrange and rearrange themselves in an absurdist ballet. Pape called this her Ballet neoconcreto I (Neoconcrete Ballet I). In 1959 she formed the Grupo Neo-Concreto, together with poets and visual artists including Ferreira Gullar, Reynaldo Jardim, Lygia Clark and Hélio Oiticica. These artists treated art objects as things with a life beyond the closed world of the art market. They made work people could touch and in which they could participate. In the centre of the gallery is Pape’s Livro da criação (Book of Creation), a pop-up book with free-standing pages, a series of 16 gouache paintings on paperboard, each one showing a phase in the evolution of humankind. Facsimiles are available for visitors to manipulate in the final room of the exhibit. The largest wall of this last room is host to Pape’s 365-piece Livro do tempo (Book of Time). Here, each relief is a square, disassembled, chopped and screwed, painted again in classic Mondrian hues: black, white, yellow, red and blue. They’re made out of wood, but look like origami creatures or Pac-Man characters.

Ballet neoconcreto I (Neoconcrete Ballet I), 1958, single-channel digital video, colour, sound, 19 minutes, 35 seconds, performance at Fundação de Serralves—Museu de Arte Contemporânea, Porto, Portugal, 2000. © Projeto Lygia Pape.

By 1969 a military dictatorship that would last for more than 20 years had taken hold of Brazil. Many of Pape’s collaborators, including Ferreira Gullar, Lygia Clark and Hélio Oiticica, went into exile, and she was held in prison and tortured for three months in 1973. A small, dark gallery shows a series of films made in these years. Pape worked in collaboration with leaders of Brazil’s Cinema Novo movement, Glauber Rocha and Nelson Perreira dos Santos, though she was uninterested in their use of guiding plot lines. Some of these films revive Brazilian modernist ideas and imagery, grappling with the nation’s colonial history and mythology, occasionally veering toward the anthropological, but preferring chance and nonsense to fact or plot. In Catiti-Catiti, 1978, a voice-over recites a letter written by a Portuguese knight who landed on the coast of Bahia in 1500, saying, “Ah, Jesus, who will populate these lands?” Pape tackles the question with wry humour, enlisting the poet Luís Otávio Pimentel to play a white man, a black man and an Indian man at once. Another film shows Divisor, a performance piece in which a giant sheet is laid over a group of people, who poke their heads through holes in the fabric to parade united through Rio.

The heart of the exhibition is kept in the dark. In a room with only small points of directed light, spindly golden threads stretch from floor to ceiling like heavenly beams in a Giotto fresco. The installation, which has taken varied forms and has occupied both public and private spaces since 1976, is entitled Ttéia, or “web.” The way the strings are lit makes it impossible to distinguish where each thread begins or ends. This loss of depth perception reminds me of stepping into a James Turrell installation, or wandering into a spider’s web in the woods.

Pape is a minimalist with an electric sense of possibility, and her work is an invitation to throw the dice. “I am intrinsically an anarchist,” she once said. “That doesn’t mean I’m disorganized. But I have this terrible inclination not to respect rigid structures.” At the exit, just as I thought she might be winding down, the last pieces from her career offer an explosion of new forms and colour. Brilliant red feathers coat a table and two chairs, making up three squares that nod to her early geometric abstractions, but there’s a twist: a breast is glued to the back of one of the chairs, and another breast lies nipple-up on the table. Here, I was left to wander out, with Pape’s last laugh ringing in my ear. ❚

“A Multitude of Forms” was exhibited at the Met Breuer, New York, from March 21 to July 23, 2017.

Georgia Phillips-Amos is a British- American writer. She grew up in Málaga, Spain, and Long Island, New York, and has worked at Verso Books and New Directions.