Lygia Clark

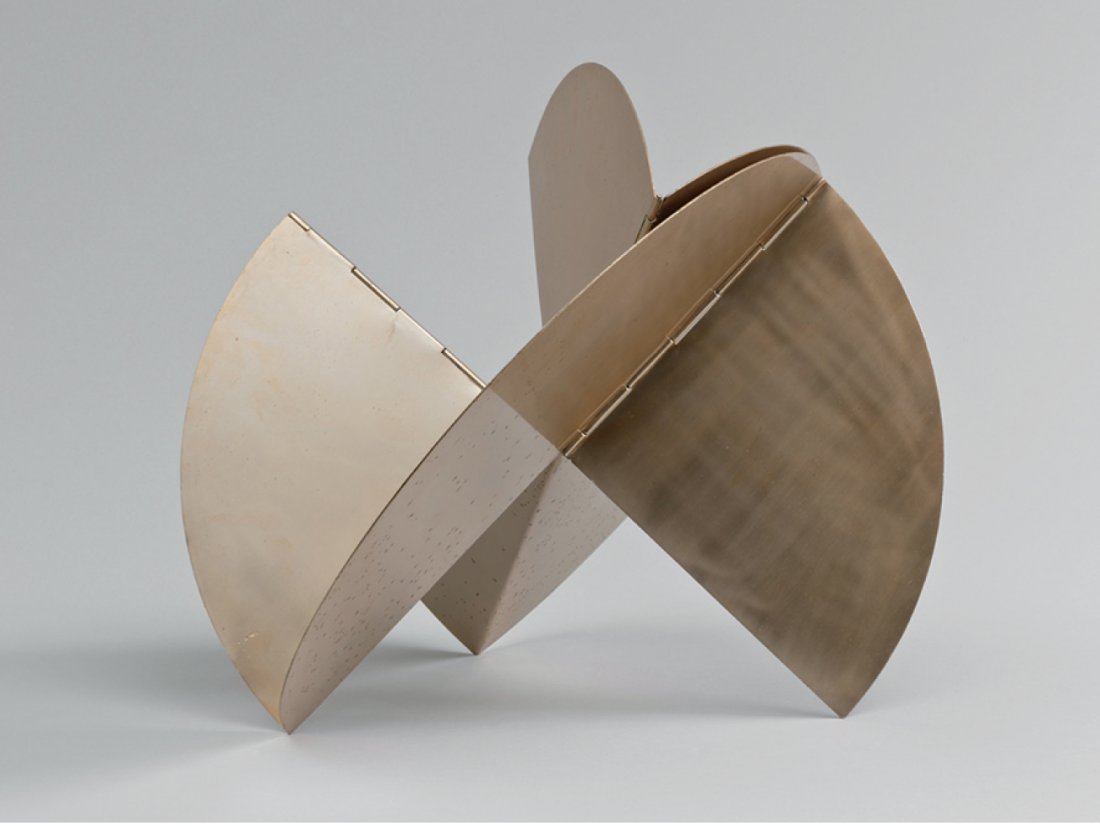

Among the most beautiful and dramatic works in the exhibition, “Lygia Clark: The Abandonment of Art, 1948–1988,” were the “Bichos” (critters)—large, metal, hinged-plane, transformable sculptures that invite the viewer to rearrange them into various shapes. It’s the first time in the MoMA’s history that three-dimensional artworks have gone on display without barriers to viewers. About these curious creatures created in 1960, Clark wrote, “[Jackson] Pollock has his ritual, but it only serves for him to express himself, while the Bichos offer ritual to the viewer as the first experience.”

With over 300 pieces that survey the Brazilian painter, sculptor and performance artist’s phases in abstraction, Neo-Concretism and an “abandonment of art,” this exhibition represents the first North American retrospective of work by Clark (1920–1988). It also newly reconsiders her oeuvre in light of her self-termed “non-art within art” after 1966, and her abandonment of art after 1976, in favour of psychotherapy research and practice. With the exhibition’s title, the curators signal the destabilizing, radical shifts inherent in Clark’s work—and it does seem as though the artist’s winding path constitutes a series of reversals or abandonments: of painting, of the art object per se and eventually of art altogether for therapeutic practice, and finally, the abandonment of therapy itself, for a return to art. The exhibition diminishes conventional divisions between media and explores instead the development of Clark’s artistic ideas.

Lygia Clark, installation view The House is the Body, 1968, “Lygia Clark: The Abandonment of Art, 1948–1988,” Museum of Modern Art, New York. Photo: Thomas Griesel. © 2014 Museum of Modern Art. All images courtesy the Museum of Modern Art, NY.

The “activation” sought by Clark through her “Bichos” can be traced both forward and back in her work. Drawing on her early architectural training and motivated by Mondrian’s aspiration to seek in painting a dynamic, spiritual geometry beyond the symbolic, romantic or immediately mimetic, Clark took the concerns of her fellow Neo-Concretists to their limit and beyond. These concerns were in recuperating sensual, organic and humanistic aspects of art from the strict formalist and cerebral thrusts of the Concretist movement that dominated Brazilian art through the 1930s and ’40s. (Clark studied in the early 1950s in Paris under Fernand Léger and others, then returned to Rio. Though she was better recognized in Brazil, her art was shown in both Europe and Brazil.) Her experiments in painting throughout the 1950s led to her discovery of the organic line, a free-floating or incised line that extended the logic of modulation—doors and windows in her early architectural models—to the two-dimensional plane, opening an interior space of painting and inviting the viewer to imaginatively complete the work.

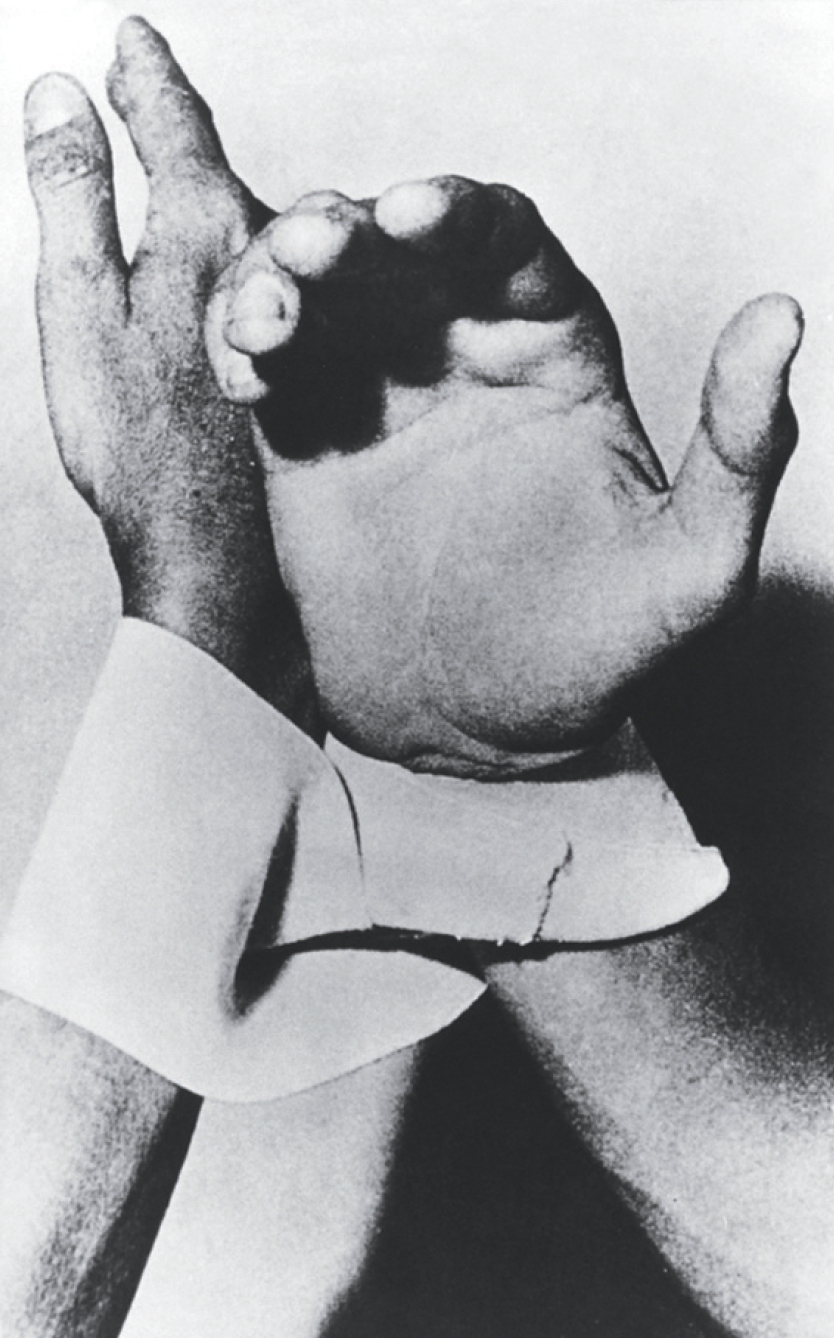

Her 1963 work Caminhando (Walking)—recreated for the MoMA show—invited viewers to make, and then cut into ever-thinner lines, a paper Möbius strip. Caminhando is not an artwork, but a proposal. It extends Clark’s fascination with the idea of a temporal activation in the viewer and with an afunctional line. A continuous plane that traversed inside and outside simultaneously, the device was used again in her 1966 work, Diálogo de mãos (Dialogue of hands), in which a bandage configured as a Möbius strip connects two people’s wrists.

“We are the proposers: our proposition is that of dialogue. Alone we do not exist. We are at your mercy,” wrote Clark of her newfound understanding. “We are the proposers: we have buried the work of art as such and we call upon you so that thought may survive through your action.”

Lygia Clark, Relógio de sol (Sundial), 1960, aluminium with gold patina, dimensions variable, approximately 20-7/8 x 23 x 18-1/8 inches. Museum of Moden Art, New York, gift of Patricia Phelps de Cisneros in honour of Rafael Romero. Courtesy Associação Cultural “O Mundo de Lygia Clark,” Rio de Janeiro.

Her sensorial objects and masks created between 1966 and 1968 (also recreated for viewers to experience at the exhibition) were other propositions that invited participation and pushed the art object further into abeyance. Later grouped together as Nostalgia do Corpo (Nostalgia of the Body), the works also related to her architectural installation, A casa é o corpo. Penetração, ovalação, germinação, expulsão (The house is the body: penetration, ovulation, germination, expulsion), shown at the 1968 Venice Biennale. Remarkably, the installation was on display at the MoMA; viewers could progress through a series of architectural chambers filled with soft materials (balloons, Styrofoam, fabric ribbons) to experience a sort of “rebirth” at the end.

In 1971, Clark reversed the configuration. “I discovered that the body is the house…and that the more we become aware of it the more we rediscover the body as an unfolding totality,” she wrote. Influenced by psychoanalysis, into which she entered after personal and health crises prompted her return to Paris in 1968, she became intrigued with the possibilities of the collective, developing participatory propositions called O corpo é a casa (The body is the house). During a gestural expressivity seminar she taught at the Sorbonne beginning in 1972, she further developed her ideas about personal, artistic and collective “disinstitutionalization,” creating proposals with her students called Fantasmática do Corpo (Fantasmatics of the Body) and Corpo Coletivo (Collective Body). After 1976, she abandoned art to begin a therapeutic practice in Rio using “relational objects” in work with patients that she called Estructuração do Self (Structuring of the Self). She returned to the art world in 1984, four years before her death.

By incorporating, assimilating or burying the art object in the act, Clark wished to bypass semiotics and transfer art’s visual erotics to the temporal realm, to the interior of the (real, phantasmatic and shared) body itself, dissolving the supports of false reciprocity and boundaries staged by the subject-object split. It was her intention that the work would expose an internal abyss for activation of a new awareness and risk, of intersubjectivity, precariousness and imminence. It may be that we are still learning how to engage with art this radical: art that displaces both object and artist, that takes as its motive a reaching beyond its own definitions (or, obversely, a kind of withdrawal), culminating in a political vision at the furthest limit of its discipline. It is so radically open that it demands from us a restructuring of the self and a reimagining of the world.

Lygia Clark, Clark’s proposition Diálogo de mãos (Dialogue of hands), 1966, in use probably by Clark and Hélio Oiticica. Object made of elastic. Courtesy Associação Cultural “O Mundo de Lygia Clark,” Rio de Janeiro.

Perhaps the most radically strange collective proposition by Clark is Baba antropofágica (Anthropophagic Slobber), 1974. One person lies on the ground while others kneeling around pull coloured threads from spools in their mouths (described by Clark as evoking a feeling of removing one’s vicera) to cover the person with the saliva-coated strings. Once all the string has been dispersed and the spit-string has been collectively figured over the prone body, the group entangles itself in the wet string and struggles together towards an ecstatic, aggressive emancipation from the threads, afterwards verbally sharing their experience.

What the artist called a “ritual without myth” is an embodied, collective encounter with a radically transformative experience at its heart. “From this comes much more than communication,” writes Clark. “There is a geometry in all fantastic creations, which are a continuous intersubjective exchange.” ❚

“Lygia Clark: The Abandonment of Art, 1948–1988” was exhibited at The Museum of Modern Art, New York, from May 10 to August 24, 2014.

Mariianne Mays Wiebe is a poet and writer with an interest in creative processes across the disciplines.