Los Canadienses: A Review

Between 1936 and 1938 twelve hundred Canadian volunteers, the “Mackenzie-Papineau Batallion”, went to help defend the young Spanish republic against the rebel general Franco. Franco, opposed only by his own people, a few thousand international volunteers, and a few raised eyebrows abroad, was given massive support by Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy. After three years of civil war and a million Spanish dead, Franco returned the old elites to their former pre-eminence and established himself in what turned out to be almost forty years of uninterrupted dictatorship. This award-winning film by Albert Kish uses newsreel footage, photographs, posters, and interviews of survivors to present a documentary of the Canada from which the “Mac-Paps” came and of the Spain to which their active idealism impelled them. Spain was a watershed in the lives of these men, an experience decisive and lasting. None appears to have any regrets, and the viewer doesn’t get the feeling that the spirits of their fallen comrades would be disturbed by anything these veterans say. Apart from the sympathy implicit in its director’s choice of theme, the film has no political bias: its subject is the human experience and the human tragedy. The political background is sketched in, and there is narrative sufficient to explain and to connect the footage, but there is no explicit political statement. But precisely because the film is politically reticient, its rich and honest human texture demands that we face and discuss its implications in terms of that sphere of life where alone the possibilities of human fulfilment are defined: the political.

Scenes from Los Canadienses.

Those who know this film only from television can have scarcely an inkling of the lyric beauty and emotional force it conveys through its proper medium, the full screen. For Los Canadienses is more than a documentary, it is a cinematic poem to an age when truth appeared simpler, though no less noble, and when commitment was less problematic, though no less heroic than today. These young Canadians went to Spain to escape the depression at home, to search for adventure abroad, and to fight for a cause. Their commitment was total: they were prepared to die and half of them did. Though they called their enemy “fasicsm”, their cause was no political abstraction. It was ordinary men and women like themselves: peasants and workers against the oppressive rule of powerful landed gentry, wealthy but unprogressive industrial elites, and an obscurantist clergy that sanctified this order and blessed the guns that perpetuated it. The face of this order, contorted in the fear of social and economic phenomena it could neither understand nor contain, became the grim and sombre visage of Spanish fascism. Or so it appeared to the veterans we meet here, and to thousands of their contemporaries from around the world who formed the International Brigades.

Scenes from Los Canadienses.

Their crusade against fascism was the last great cause because never since then has the division between right and wrong, good and evil, appeared so clearly drawn, nor has commitment to either ever been so amenable to unequivocal political choice. For two of our centuries greatest manifestations of radical evil, the Nazi death camps and the Soviet Gulag, flourished at opposite poles of the traditional right-left political spectrum. And closer to home, the meaning of any of our gestures on behalf of black South Africans today is complicated not only by our economic interest in white supremacy there, but, indeed, even more so by the extensive influence of white South African economic interests here. How much simpler things appear to have been forty years ago; certainly much of the appeal which attaches to the Spanish Civil War — witness the replays of old documentaries and the re-issues of the songs sung by the International Brigades — is explicable as moral nostalgia, a longing for a time when awareness and integrity were not incompatible.

Scenes from Los Canadienses.

Kish’s technique is reminiscent of that of Marcel Ophuls in The Sorrow and the Pity: introduce the viewer to real live people who were there, get him interested in where they were and why, and then quick cut to raw newsreel footage, to take him to the past direct without benefit of any mediation. This jars the consciousness, and by provoking the reviewer’s involvement via the initial mediation of survivors, avoids that descent into voyeurism which so much documentary entails. The principle that determine’s Kish’s juxtaposition of material goes beyond that of “objectivity” to offer both lyric beauty and moral insight. We meet these men in their seventies at their annual reunion picnic joshing in fun as they try to drink from goatskins, and then immediately cut to footage of similar faces doing the same thing forty years ago on the way to the battle front in Spain. Recent colour film of the ruins of Belchite, which the victorious fascists left as a monument to “Red barbarism”, suggests a remoteness akin to that evoked by pictures of classical ruins. But any incipient attic reverie is ended by Kish’s sudden cut to newsreel footage of the destruction of Belchite in progress, and subsequent colour shots of similar but still-standing Spanish towns shatter the hull of “remoteness” sheltering us from truth and responsibility.

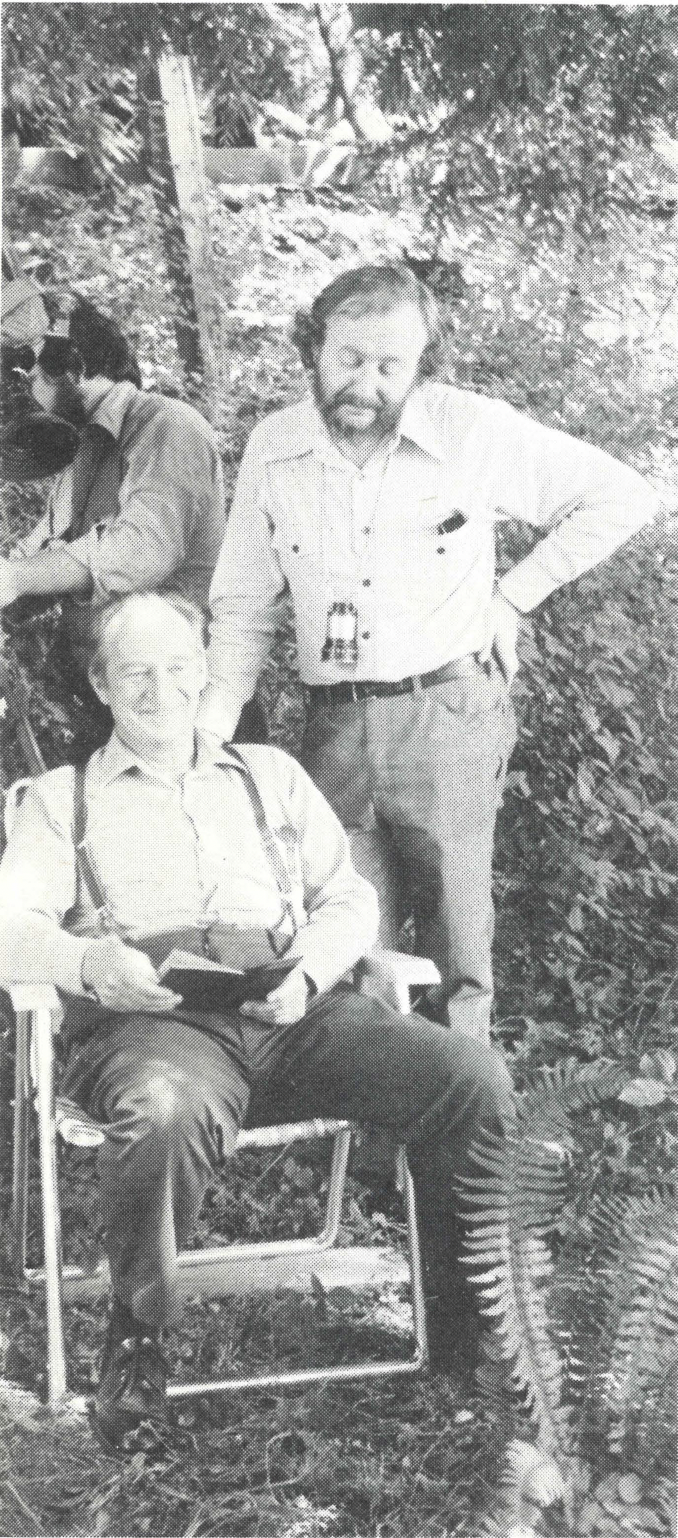

“Mac-Paps” at their annual reunion picnic.

Not that we ‘re subjected to a lot of cute cutting room work which seeks to manipulate our consciences. The real truth and beauty of this film is in the veterans themselves, recreating in their old and expressive faces the Canada of their youth and depression, recalling their motives and suppositions in going to Spain, and offering a balance sheet of their experiences there. We observe the lined and craggy face of John Schoen contemplating itself, then smooth and innocent, in a forty-year-old photograph, and we wonder what it’s wondering. The eyes of Louis Tellier are unsteady, as if trying to evade some guilt for having gone to Spain mainly because there was “no adventure going to relief camps”, and “anything would have been better than that”; Misha Storgoff, talking and singing to us in his Winnipeg Barber Shop over the wary head of a customer, conveys his conviction of fascism as a generalized evil whose demon we all fought in Europe later, thereby vindicating his illegal, premature trip to Spain. And yet his conviction has not distorted his recollection of last minute doubt while crossing the Pyrennes by night: “What am I doing here? Should we really be here?”

Director Albert Kish and a veteran during filming.

But it is in James “Red” Walsh, a Mac-Pap veteran living in Vancouver, that Kish’s fusion of the lyrical and the documentary is most poignant. With each successive appearance of Walsh, the compass of our vision gradually extends from his lone figure on the edge of a bed until it includes all the details of his bright but rather bare room in the senior citizens’ residence in which he appears to work as caretaker. He recalls with enthusiastic rage the provocations by the authorities during the Vancouver longshoreman’s strike in 1935 and the police riot in Regina the same year, events which made many Canadians realize they were “in the same boat” as the ordinary people in Spain. But neither is Walsh bitter nor does he become explicitly political. Our final image of him — and on this the film concludes — is of an old man bent musing over his broom, sweeping a walkway in the residence grounds, with people chatting on benches in the background and a tennis match in progress on the other side of a high hedge. What he had fought for, he tells us, and all that the people of Spain really wanted, was no more than “the most important and fundamental right in Canada: to go to the poles and vote every four or five years.” And that’s it. The camera recedes, the leaves swirl, and old Walsh sweeps.

Lionel Steiman has published articles on Fascism and specializes in German intellectual history. He is a native of Winnipeg and teaches at St. John’s College.