Liz Magor

Liz Magor’s exhibition “Habitude” at the Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal is the largest major survey of the artist to date, corralling a comprehensive swath of artwork from approximately 40 years of her production. Co-curated by Lesley Johnstone, curator and head of exhibitions and education at MACM, and York University associate professor of modern and contemporary art, Dan Adler, the show is scheduled to tour, with stops at the Migros Museum für Gegenwartskunst in Zürich, Switzerland, and the Kunstverein in Hamburg, Germany.

Accompanied by an excellent catalogue, a touring show of this scope provides a proper chance to more fully encounter an artist whose work gains in emotional and intellectual reverberations the more of her wide-ranging oeuvre we are able to engage with at once. Her aesthetic propositions are appreciably skilful, self-aware and thoroughgoing, as well as pleasurable, layered with good-humoured analysis and commentary. Available in large doses, her project takes on an inclusive particularity, revealing a driven, long-term plan of investigatory aesthetic research through explorative making. The work manifests substantial acumen and provides challenging enjoyments, and in “Habitude” the scope of her achievement is revealed as broadly flexible and systematically ambitious, operating across the eclectic, multivalent spectrum of three-dimensional contemporary art.

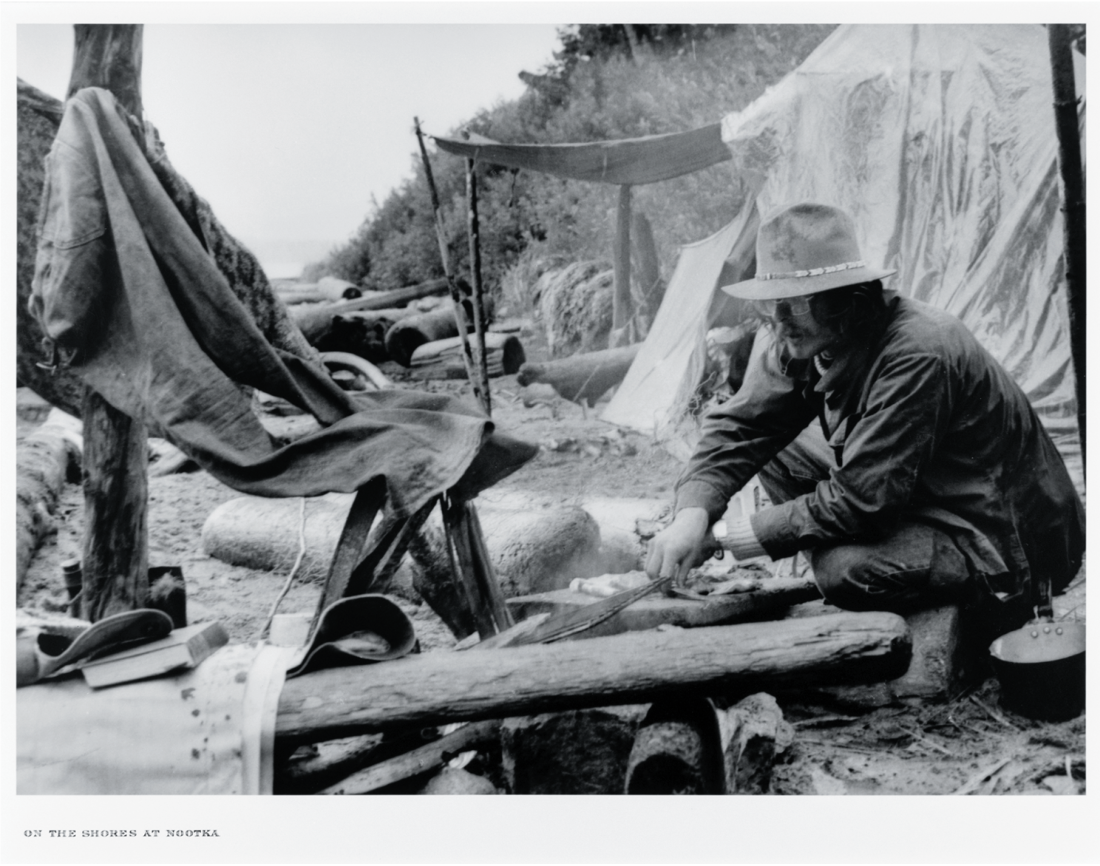

Liz Magor, On the Shores at Nootka, 1989, from “Field Work,” 1 of 10 silver prints, 55.9 x 71.1 cm. Collection of the National Gallery of Canada. Photo: Trevor Mills. All images courtesy Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal.

Magor appears to have been trying since her early maturity to respond to and utilize the poststructuralist ideas that helped form the nexus of her generation’s aesthetics—those of early Postmodernism at its most exciting—while quietly trying to incorporate a highly personal but nonetheless self-conscious form of existential subjectivism. Sixties’s culture and its aftermaths have exemplified this dichotomized identity from pop art to the Nouvelle Vague, academic Marxism to arena rock. And Magor’s work begins to disclose surprising effects as more time is spent with the show. The viewer may expect a coolly rigorous line of conceptual conclusions, especially from certain pieces that exhibit the symptoms of belonging to that area of influence. But even there a sense of private and expressive content emerges the longer we look. An example is Messenger, 1996–2002, which occupies its own room and comprises a life-sized cabin whose interior we glimpse through two windows. Mimetically, it initially seems to belong to a crackpot survivalist, and to offer a stern social critique, a warning to the viewer, perhaps about alienated ultra-conservatives going stir-crazy deep in the woods. But after an examination of the esoteric and wide-ranging objects within, which run from the found to the carefully fabricated (including a sleeping dog sculpture) and the self-evident to the very bizarre, the piece begins to emanate the oddly unsettling sense of being the lair of a misfit or hermit artist, but also some sort of complex synecdoche or cypher for the meaning set “Artist.” Messenger, a title of quiet but not literal eschatological force, is a moving demonstration of the phenomenon of necessary outliers.

Magor’s work strangely seems to belong to minimalism and conceptualism the more she forces the boundaries of what those systems have conventionally accepted, proving by experimentation that the rules themselves are provisional and subject to redefinition. It seems accurate to call her a post-minimalist with strong conceptualist aspects, but Magor’s practice contains the mass and gravity to be seen as its own world, not a satellite of someone else’s— artist or theoretician.

In the process-based work Production, 1980, she exhibits both the means of production and the product of her labour—a large multi-sided wall of paper bricks and the machine she used to make them—cannily implying that the visual strength of the result is in the meaning of the process, while the piece’s formidable physicality derives from the rigour of its planning and execution. This kind of QED is everywhere in “Habitude” but doesn’t seem hectoring or academic and is communicated without loss of sensuous immediacy.

Stack of Trays, 2008, polymerized gypsum, chewing gum, found objects, 25 x 45 x 47 cm. Private collection, Calgary. Photo: Scott Massey.

There is a plethora of different artwork to consider, from her trademark shelf pieces and installation of naturalized and synthetic animals, to her frequent use of polymerized gypsum as the tabula rasa onto which to inscribe a multitude of subjects, to the majestic recent piece The Good Shepard, 2016, which occupies its own wall and synthesizes beautiful formal presence with keenly objective presentness, and much more. She offers materials and meanings of and in enormous variety. The show makes finely explicit Magor’s configurations of space through the precise use and installation of materials which she deploys in ways that are both innately self-referential and indexical in their rotating axes of reference. The work subtly blurs the line between an academically professional exploration of theoretical propositions and putative tropes, and a private language of existential expression.

In the piece Cabin in the Snow, 1989, a quiet analogy is drawn between the meaning of northern (perhaps tacitly Canadian) identity and artistic inspiration, as we look through a darkened glass window to catch a glimpse of a small model-like wooden cabin, glowing from within with a quietly warm light, in the middle of a midnight expanse of snow. The value of real-world solitude imaginatively takes shape the longer we view this vision of a soft sublime. Any possible saccharine feeling is absent, frozen out of possibility, in a subject that risks a too-easily romanticized or comforting reading with clear artistic sure-footedness. We are in fact situated in a peacefully firm manner in diachronic time, observing and feeling the force of Magor’s wintry beacon, as though we are headed home, and it seems to expand and fill the landscape with a growing inner self, possessing both knowable and unknowable elements, a voice and a message from the other side of the dark glass.

It’s gratifying and exciting that the show is going to be seen in Europe (albeit in a somewhat smaller incarnation) since it’s often a rarity, even for the artists considered the most important in Canada, to get that chance. “Habitude” proves that Magor is certainly worthy of the opportunity.❚

“Habitude” was exhibited at the Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal from June 22 to September 5, 2016.

Benjamin Klein is a Montreal-based artist, writer and independent curator.