Liz Canner

A crowd of about 60 gathers in downtown Saskatoon at dusk. Projected on the Police Service building, a two-by-five-metre video image shows local resident Donna Heimbecker’s day beginning as she drives through the city of bridges. Her voice emanates from a speaker system: “An Aboriginal man was taken and driven out of town by police officers and was left there to freeze to death in the cold of winter. There have been other incidents in and around Saskatoon where Aboriginal people have been found frozen to death… and of course Aboriginal people are going to live in fear wondering, ‘Am I going to get taken in the back of a police car and dropped off?’” Heimbecker, the general manager of the Saskatchewan Native Theatre Company, is a Métis woman who donned a miniature camera mounted on eyewear frames to record a day in her life.

A uniformed officer joins the audience, watching from the entrance to the building as the image splits into two views. Now we see through the eyes of the second documentary subject, Constable Keith Salzl, a non-Aboriginal officer who left his patrol duties a few years ago to become one of two Aboriginal liaison officers in the Saskatoon force. Heimbecker arrives at Salzl’s home and meets his wife, two children and two dogs. The friendly encounter belies the horror of Heimbecker’s initial words, a powerful statement to be aired in front of the police building in this city that has been living for 14 years with the mystery of who killed 17-year-old Neil Stonechild, the first Aboriginal man found frozen on the outskirts of Saskatoon.

Liz Canner, Bridges project, Donna Heimbecker, General Manager, Saskatchewan Nature Theatre Co., and Keith Salzl, Aboriginal Liaison Officer, Saskatoon Police Service. Photograph courtesy paved Art + New Media, Saskatoon.

The Stonechild inquiry, finally launched last year, is the hidden backdrop to Bridges, the hybrid creation of New York artist Liz Canner, made during a three-week residency hosted by paved Art + New Media in Saskatoon. The public art project was initiated by a local coordinator, artist Ellen Moffat, who laid the groundwork by involving members of Saskatoon’s Aboriginal community. The project’s purpose: build intercultural relationships, dispel stereotypes and, as Canner said in an interview, “really let the subjects tell their story in the way they wanted to.”

Canner’s strategy is to put her subjects behind the camera, using wearable video technology developed by cyborg genius Steve Mann, get them to interact, and project their day on a public building that has symbolic value. This is Canner’s third such project. Symphony of a City, 2001 (with muralist John Ewing), projected onto Boston City Hall a day in the lives of citizens involved in the urban housing crisis. Last year’s project in Arlington, Virginia, which looked at issues of freedom post-9/11, put a wearcam on, among others, a Muslim woman helping the families of men incarcerated under the notorious Patriot Act.

Canner, no stranger to issues of racism and police brutality, once made a documentary about the Los Angeles Police Department that was virtually censored in the United States. That is what makes the Saskatoon screening so remarkable: Police Chief Russell Sabo embraced the Bridges project (although he declined the invitation to don a wearcam). It is an indication of the police department’s desire to heal divisions between a mostly white police force and the sizeable Aboriginal community.

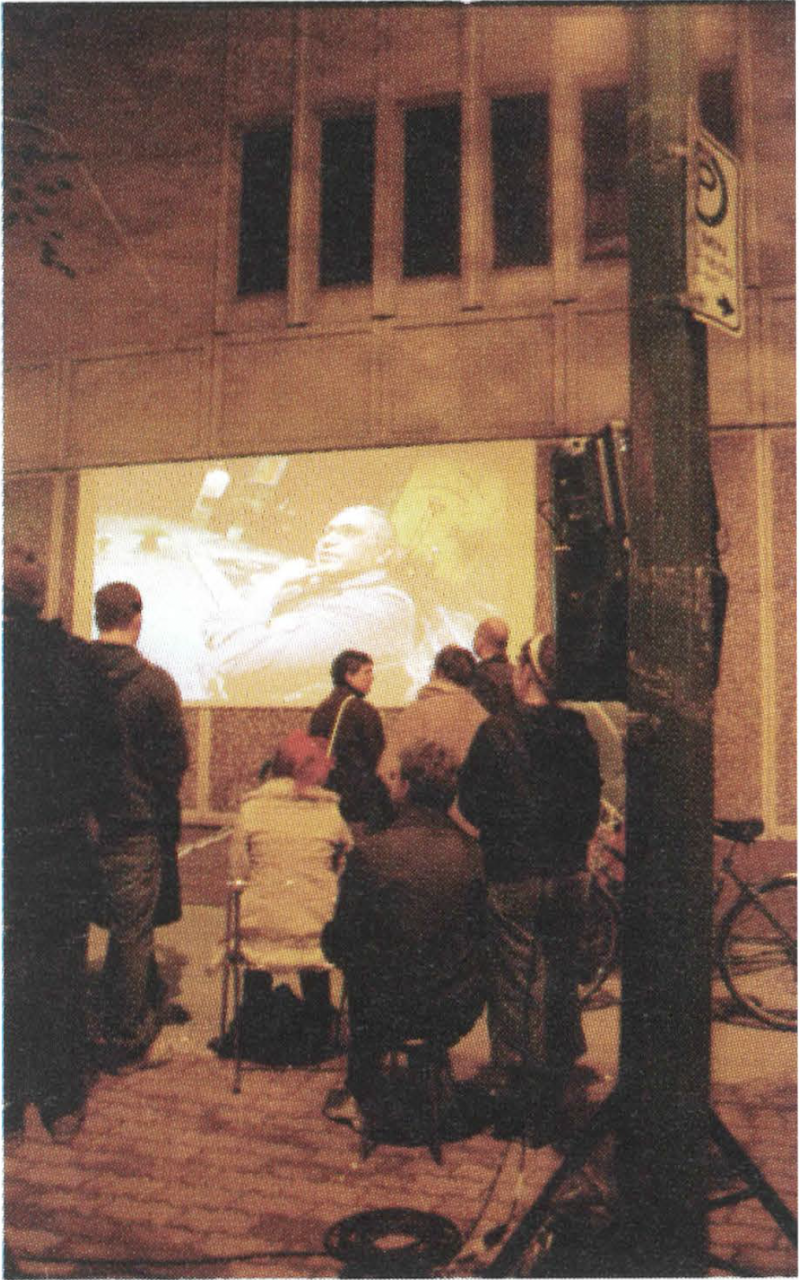

Liz Canner, night video screening, Saskatoon Police Services Building.

For members of the Aboriginal community, which was given the power to choose who wore the cameras, the project was an opportunity to circumvent the mainstream media, allowing an Aboriginal point of view, through the split-screen imagery, to achieve a kind of equality of representation. It was also a reclaiming of public space as an arena of democratic discourse. Nick Capasso of DeCordova Museum, who curated Canner’s Boston project, wrote, “One of the wonderful and exciting things about public art pieces that use projected imagery is that they, for a brief time, radically change a surface in the public realm…. These images are often intentionally large. They want to inhabit the space, but they also want to inhabit the imaginations of the viewers to the point where the experience of that piece … will linger in memory and affect people’s thinking about the space itself.”

Through the eyes of Heimbecker and Salzl we see some commendable initiatives taken by both communities to deal with disempowered Aboriginal youth: alternative sentencing, talking circles and arts programs. Still, the overall effect is strangely discordant. The fact remains—never specifically discussed in the video—that no one has ever been charged in the deaths of Neil Stonechild, Rodney Naistus and Lawrence Wegner. Bridges presents a formal vision of equality through its split-screen image, but it is embedded in a social context of inequality. That is what makes the site of its screening so jarring, and effective. It raises questions that go beyond the actual content of the video, suggesting an investigation of power and the efficacy of public art to foster understanding and dialogue in a racist society. ■

Bridges was presented by paved Art + New Media on May 29 as part of “SPASM II: The Couture of Contemporaneity,” a public art festival held in Saskatoon from May 28 to June 6, 2004.

Maureen Latta is a Saskatoon-based freelance writer.