Lisa Klapstock

I should confess from the outset that my critical eye is more attuned to painting than to photography. But in the case of Lisa Klapstock’s recent works, the concerns of the two overlap, especially around the issues of space, place, the self and sublime utopian visions. Klapstock’s photographs, done over a number of years, are divided into a series of four suites. The first, among the smallest in scale, is titled “Threshold.” These ongoing investigations were taken in Toronto’s urban alleys, an ambiguous backside locale that Klapstock seems to favour. The views are shot through knotholes, nail holes and cracks between boards in fences. They position both the photographer and viewer as surreptitiously standing in a public space and stealing a fleeting glimpse of a private realm. The restricted images are, however, always uninhabited. Although in focus, only sharply cropped fragments of windows, walls, chairs and greenery, bits of edenic, but urban, gardens, are visible. This frustration with completion and occupation mitigates against the sensation of voyeurism associated with the violation of property divisions, restrictions of sight and invasion of privacy. The fences, in contrast, are, although close up, blurred into almost flat, non-differentiated, immaterial fields. which take up most of the surface of the print. The contrasting holes or vertical bands of vision that punctuate them are composed like Barnett Newman’s painterly zips. But the implied sublimity is of the everyday, momentary and withheld, rather than the universal, eternal and immanent. The contrast between the specific and non-specific is increased through the titles, which give the precise address of each location, but withhold one of the numbers, which is replaced by a generic asterisk.

Lisa Klapstock, Crawford Street (from the “Threshold” series), 2001-02, c-print, 17 1/2 × 17 1/2”. All photographs courtesy the artist.

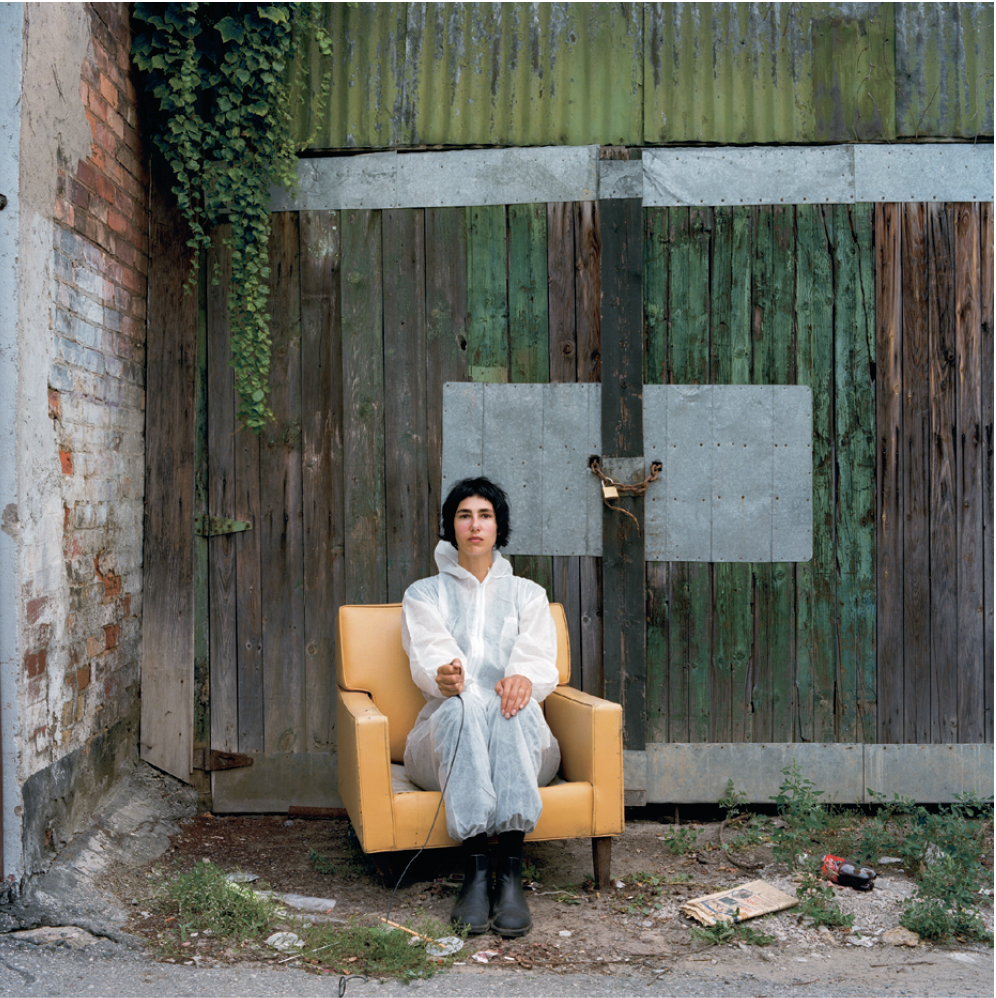

In the second ongoing set, titled “Living Room,” which dates from 2000, the works grow in scale. Klapstock stays in the alleyways, but introduces her own presence, turning the camera on herself. Here the artist sits on outcast, discarded and dispossessed pieces of furniture, remnants of bygone, low-end styles in plush, plaid and faux leather, from which the individual pieces take their titles. These abandoned, derelict objects suggest the failure of the modernist promise. The clearly focussed surroundings are dilapidated garage doors, peeling paint, tilting eaves, slipping shingles, broken concrete and weedy growth; in short-decay. The sense of melancholic ruin, a trope drawn from painting, is enhanced by the grey, shadowless and subdued lighting. Contrasting hand-painted signs warning against parking or dumping, and prohibited signs of spray-painted graffiti, suggest attempts to use painting and text to either regulate or resist regulation. The failure and frustration on both counts add an ironic and subtly humorous note.

Everything is shot straight on and arranged in flattened and carefully composed interlocking rectangles with little perspective, like the modernist grid, which has, in the painting of the last century, signified a utopian vision. But this neglected section of urban utopia is best avoided. In its midst, Klapstock has placed herself, sitting primly on the furniture in non-expressive poses. She is uniformly dressed in an antiseptic, protective white overall, avoiding the contagion of this potentially toxic environment, but also displacing her body and rendering her without personality or individuality. The homogeneity of both the images and the artist’s presence again plays the differentiated against the non-differentiated, a contrast further enhanced by subtle details such as the cutlery delicately placed beside her in one image.

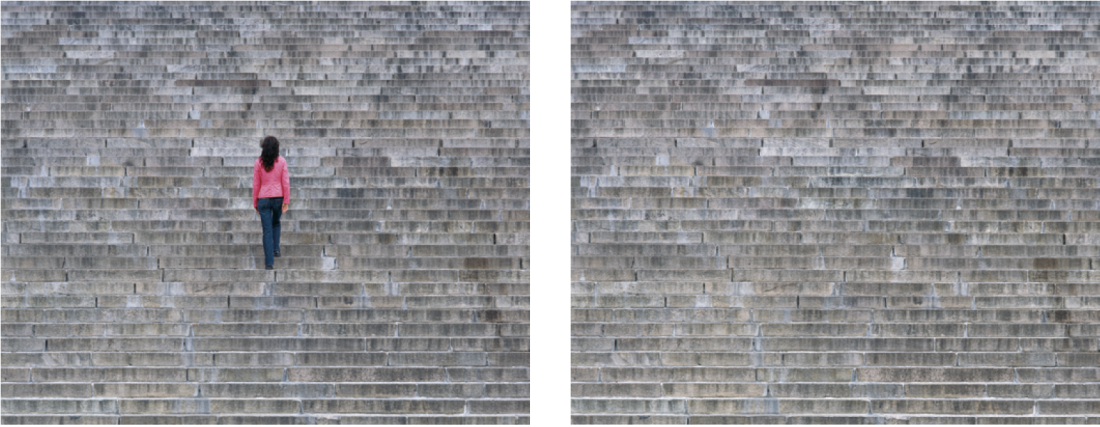

Lisa Klapstock, Helsinki (from the “Ambiguous Landscapes” series), 2004, c-print, 4 x 5’ each.

The third ongoing series, the “Ambiguous Landscapes,” is the most recent and, at four by five feet, the largest. Three profoundly different sites are each represented twice: a monumental flight of grey stone steps from a popular tourist spot in Helsinki; a barren field of dark grey asphalt from Zeeland in the Low Countries; and an arid, sage-covered, high plateau hillside near her former home in Kamloops, British Columbia. Although the titles taken from these places point out the diversity of subjects, they have a commonality. Each image hovers between the sublimely non-differentiated and the incredibly specific, in a manner drawn from painting but befitting photography. All three images are intensely detailed, the result of using a great depth of field to achieve consistent focus over the entire field, and shot from a distance so that shifts in scale are minimized. Implications of visual infinity are arrested by the consequent flatness of the image. The horizontal expanse of pavement, like an airport tarmac, and the steep, vertical hillside are both sharply divided from the matte grey or blue skies above them, the first through its barren expanse of man-made materials, the second through its softer, but equally continuous, field of natural, tenacious sage. The steps of the third mediate between the high and low found in the first two. The staircase has no horizon, but extends in repeated and uniform bands from bottom to top and side to side, like a classic Minimalist painting by Agnes Martin. But unlike this precedent, Klapstock appears bodily in three of the six, leaving the other three unpeopled. In each, the artist wears a bright red jacket in a passionate and sensuous hue, which situates her diminutive, definite, but non-defined figure almost intrusively in the vastness of the otherwise empty spaces.

Lisa Klapstock, Yellow Armchair, 2000 (from the “Livingroom” series), c-print, 34 1/2 × 34 1/2”.

The last series on exhibit, “Umbilicus, Spectrum,” which has been ongoing from 2001, gives a humorous twist to speculation on the representation of the sublime. The most object-like of the works, this series is composed of ordered grids of small half domes of clear acrylic, set over rainbow-hued photographs of small disruptions in otherwise continuous surfaces. These bits of decay in the pristine flatness appear, through the overlaying and magnifying lens, as belly buttons. This visual pun suggests that photographic navel gazing must include a belly laugh and a bit of self-deprecation to avoid the overstated rhetorical gestures of others engaged in this field of inquiry.

In Banff, following the first installation, Klapstock added to the “Ambiguous Landscapes” with a series of sublime white-on-white photographs of the snow in the mountains, in which there was only the merest hint of definition. She is developing an accompanying multiscreen video work depicting the same landscapes as the photographs. The videos are largely still, with the only movement being Klapstock’s figure as she passes through the frame. In the video component of the Banff piece, Klapstock’s body, dressed in black, appears and disappears into the white field/void. The videos magnify her vision substantially. ❚

Lisa Klapstock’s “liminal” was on exhibit at the Southern Alberta Art Gallery in Lethbridge, Alberta, from November 27, 2004, to January 16, 2005. The exhibition will travel through 2007 to the Tom Thomson Memorial Art Gallery, the Kamloops Art Gallery, the Robert McLaughlin Gallery and the Owens Art Gallery.

Leslie Dawn teaches art history and critical theory at the University of Lethbridge.