“Lines of Difference: The Art of Translating Islam”

We have come a long way from identifying Canadian art with the Group of Seven and presentational Inuit sculpture, but clichés die hard. Happily, the young artists in this exhibition, assembled by the bright new curator Noor Bhangu, are up for the fight.

Challenges to the hegemony of Canadian art clichés have already figured in feminist, socialist and conceptual art since at least the 1960s, but more explicit critiques of the whiteness of Canada’s culture have become common only recently in new exhibitions such as this one and in First Nations art. I’m white and even I’m tired of Canada’s lazy hidden assumptions of white superiority. Many of us are tired of the mainstream, but these young artists are menaced by it every day. Racism, after all, is as Canadian as Wayne Gretzsky.

Hassaan Ashraf, !سَمَجھ ہَر اِک رَاز کو مَگَر فَریب کھَائے جَا, 2019, text-based installation. All images courtesy La Maison des Artistes Visuels Francophones, Winnipeg, Manitoba.

Canada’s official multiculturalism policy, forged in the optimism of Expo ’67, looks shiny on paper, but pressure on immigrants and First Nations to assimilate themselves into British colonial modalities remains. Islamic artists from places such as Pakistan and India have endured British colonialism since long before Canada existed as a country. A Pakistani friend of mine who recently immigrated to Canada, for example, fluent in seven languages, gets frustrated when Canadians compliment him on his command of English even after he tells them that English is his first language. At birth he was granted both the gift of a British heritage, like white Canadians, and the curse of British condescension.

Fraught relations between mainstream Canadian culture and contemporary Islamic art are highlighted in this show by Hazim Ismail’s and Hassaan Ashraf’s refusal to translate their texts for English- and French-speaking audiences. Avant-garde provocation lives, as this show, called “The Art of Translating Islam,” literally includes untranslated material. Noor attributes this to “a common desire to simultaneously translate and obscure cultural nuances from the controlling vision of a general\ public.” Contemporary Islamic avant-garde can taunt its audience.

Omar Elhamy and Philippe Leonard, Noah, 2019, video installation.

These artists have attended contemporary art schools and work with international art-world forms and techniques, which makes me wonder about Islamic artists in Canada who make vernacular art. Canada’s regions have folk artists, and earlier First Nations art includes non-art-school Woodland artists, so I assume a little research might expose vernacular Islamic Canadian artists as well.

Beautiful paintings by Zahra Baseri in this show make references to Islamic patterning but break with vernacular traditions by including social commentary (that abstract painting can include social criticism is a hot topic these days); Rah Elen’s mesmerizing self-portrait video has her “passing” as a white pop star reminiscent of Madonna and Lady Gaga; Hazim Ismail is a performance artist as well as a poet; and Omar Elhamy and Philippe Leonard make contemporary installation art that would look fine in a contemporary biennial.

Elhamy and Leonard’s dreamy room, called Noah, greets viewers as they enter the exhibition. A flickering video is viewed through a hanging set of filters, a projection of what looks like a tropical zoo with shadowy tourists in the foreground. I scanned the panorama for animals, but none were visible. Perhaps this exotic enclosure is a metaphor of humans made exotic by cultural fiat, as if viewed through a prism.

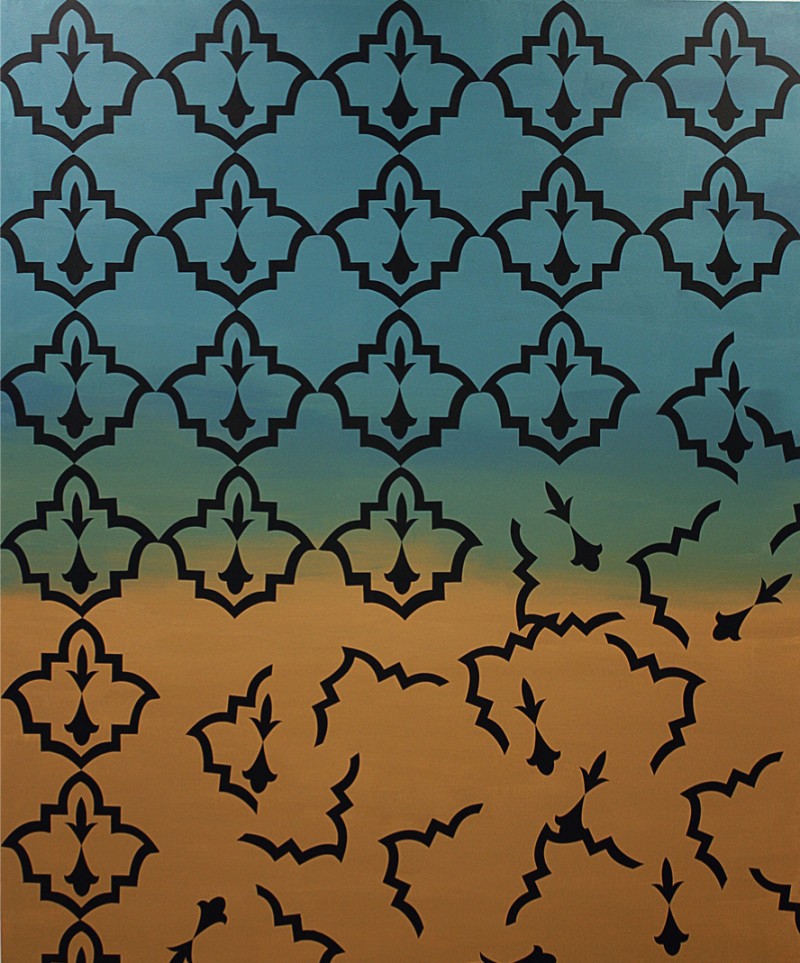

Zahra Baseri, Outcry #1, 2016, acrylic on canvas, 183 x 152 centimetres.

Zahra Baseri’s painting Outcry #1 incorporates an Islamic decorative motif that breaks down at its base into fragments, as if formal play is about cultural breakdown. I’m reminded of the cultural transitions these artists have experienced in North America, and also that several of these artists are culturally Islamic but secular people. This might be too coded a reading, but it seems right in the context of a show in which there is no explicit mention of religious belief but an emphasis on Islamic culture. It is also a reminder of references to Islamic art made by Western artists such as Matisse, who incorporated decorative allusions to Persian/Mogul book painting in early works such as The Red Studio. Matisse has been taken on for his exoticized odalisque paintings, recently, for example, by Lorissa Rineheart in Hyperallergic magazine (online at Hyperallergic, March 12, 2019) in terms of “undiscussed sexual exploitation,” a theme in Western art also made famous in Delacroix’s and Picasso’s “Women of Algiers” paintings.

My describing this exhibition as being “new” for Winnipeg, an wondering about vernacular Islamic Canadian art, is an invitation to those in the know—or who want to know—to articulate histories of Islamic art in Canada. Like women’s art, which not so long ago was presumed not to exist, and then found miraculously to have always been everywhere, Islamic Canadian art will broaden into the future and into the past, giving curators like Noor Bhangu lots of work to do. ❚

“Lines of Difference: The Art of Translating Islam,” curated by Noor Bhangu, was exhibited at La Maison des Artistes Visuels Francophones in Winnipeg from April 4 to May 25, 2019.

Cliff Eyland is a Winnipeg artist.