Letter to a Young Artist

Buy some acrylic paints, paper, canvas or wood. Cover the surfaces with acrylic gesso and then with paint. Make your paintings without using models or photographs, the way you did when you were a child. If you paint a human figure, do one from your imagination. Use various kinds of paints and brushes. Begin with the colours red, yellow, blue, black and white. Make a drawing with a brush starting with thin paint and build it up. Don’t get too thick too fast. Improvise with and react to what happens as you mix paint and spread it over a surface. Look at your painting for at least as long as you apply paint to it. Scrape at the surface. Fuss with it. Add more paint. Remove paint. After you have finished or given up on the first painting, paint another picture, and another, and another.

Look at paintings by other artists. Your painting can lead to more paintings, to video, photography, sculpture or performance art. It could also lead you to think that you’d rather not be an artist. Painting seems easy at first, but serious painting is not only the technical handling of paint but also an evaluation of your painting and your guess as to where you might go with an infinite set of choices about what and how to paint next. It also has to do with what you refuse to paint and what you would never paint.

The worth of your first few paintings, or even the first few years of your paintings, will likely be educational and technical. If you are new to painting and you are young, you may have been encouraged all your life to think that everything you do is good, so you know about this trap already. You need to give yourself some encouragement to continue because your first work will likely be a failure or a tentative start or something you can’t really believe in, but you must be honest with yourself. You have been attracted to painting for what theorists call ideological reasons, that is, because of the Romantic ideas that run deep in our society and have been amplified in movies and books about Van Gogh, Frida Kahlo and Jackson Pollock, to name three. These Romantic ideas can motivate you but they can also prevent you from going astray, which is not good; for example, you might feel that graphic art and computer programs such as Photoshop are less worthy than traditional painting. Hollywood has yet to make a Romantic hero out of a Photoshop artist, but it might happen. Whatever. If you are steered toward painting’s allied mediums then I urge you to follow your instincts. Photoshop is painting and cartooning can be art. But don’t default to drawing just because you think it is easier than painting, it just seems easier.

Cliff Eyland, Sculpture in Landscape, 2014, acrylic on MDF board, 5 x 7 inches. All images courtesy the artist.

You should continue to make paintings as you agonize over the fraught question “is this a good or bad painting?” Paintings are judged by discussing technique and subject matter and context, and an important part of your context is that you are learning how to paint. That should not make you feel better about your painting, but it can make you suspicious of people who grant you a pass because you are a beginner. You need to be critical, but you also need to be a little gentle with yourself or you won’t make anything at all.

My advice is to make small claims for originality and revel in them. That should keep you going. No two brushstrokes are exactly alike and this tiny claim of originality is yours from the start. You will also note that no two contexts are alike and the circumstances of your painting are unique, however ordinary. Your biography is unique, even if only barely unique. All of this can be added to the defence of the small originalities of your work.

When I was young I liked paintings that I thought, and in some cases still think, were technically easy to make. Another trap. I thought, for example, that Joan Miró was easy, and that Georges Rouault was easy and that folk art was easy and so I imitated them, with bad results. My early drawings were mere outlines. The right way to proceed, I thought, was to carefully outline a form and to then fill it in, and that must be how painting works. That can work for some painters, but not for, say, Manet or Velasquez or Lucian Freud.

I drew, and still draw, obsessively, but drawing and painting are different from each other. Ideally you should draw for years before you make that first painting, but most of us just plunge in and paint as we draw and draw as we paint. Painting involves blending paint and blended paint is hard to control. That might be why many painters used to begin with just black and white and grey as colours. It is hard to anticipate what you have to do to make a complex painting, even if you have read up on techniques and have looked at all the YouTube instructional videos. I think differently when I paint—more dreamily. I tend to think in exactitudes when I draw and in vagaries when I paint. Drawings can be erased but painting depends on a constant improvisation in which an erasure can be accomplished, paradoxically, by adding paint. A painting is as much followed as it is willed into being.

Girl, 2006, 5 x 3 inches.

Compare your paintings to paintings by other painters. You do not have to do this, of course, and your painting will not be disqualified as art just because it looks like hundreds of other people’s paintings or because you know nothing about the history of painting. In fact, a painting can be very successful if it looks like other contemporary paintings in precisely the right way, but that is a fleeting pleasure.

If you are painting a still life you’ll want to look at the Dutch masters and Giorgio Morandi and Pierre Bonnard and Gwen John and Goodridge Roberts (you’ll note that artists like to talk about dead artists); if you are painting a landscape you’ll want to look at living artists such as Dorothy Knowles and Monica Tap and Kim Dorland and Peter Doig, but also dead ones such as Lawren Harris and Claude Monet and JMW Turner; if you are painting a portrait you’ll want to look at Janet Werner and Alice Neel and John Singer Sargent and hundreds and hundreds of others. If you love figure painting there are too many artists to look at, but you might start with Neo Rauch, Kent Monkman, John Currin, Lisa Yuskavage and David Salle. If your painting takes a turn to abstraction you will want to have a peek at Harold Klunder, John Kissick, Amy Sillman and the Bauhaus and Abstract Expressionist artists and Mondrian. If your painting becomes three-dimensional you should look at Jessica Stockholder and Robert Rauschenberg. If your painting always turns out to be a drawing—always graphic—maybe you should look at artists such as Chris Ware, Robert Crumb, Julie Doucet, Seth and Art Spiegelman and hundreds of other cartoonists.

You are welcome to seek out any authority you like. You will be happy to know that many famous artists have admired and copied their heroes: the young Monet was obsessed with Manet; Picasso and Braque steeped themselves in Cézanne, and Van Gogh went from one infatuation to another in record time. When you become a mature artist you will make your own judgements—right or wrong—about the worth of your work, the world be damned, but don’t damn the world, and especially its artists, too soon. Recently Dr. Jeanne Randolph and I conducted sessions billed as an alternative graduate school at Modern Fuel gallery in Kingston, Ontario and at the Eastern Edge Gallery in St. John’s, Newfoundland. Such projects are being attempted all over the world right now.

Wreath Tree, 1989, acrylic on Masonite, 5 x 3 inches.

Although we seriously questioned the worth of the contemporary graduate art school and its ever rising set of supposedly necessary credentials, it became clear to me during these sessions that some acquaintance with undergraduate art school was essential for our participants.

You’ll want to attend an undergraduate art school to help sort out your thinking. Art school critiques are polite these days but at every level they make plain a common indifference to mediocre work since it’s the good work that gets praised. You might think better of your work by asking for criticism and getting some, and art school can arrange that for you. Sadly, perhaps, there are vanishingly few contemporary artists of note who have not gone to some kind of art school (Allan McCollum and Andrea Fraser are examples) and hence few for you to look up to.

When you do go to art school you will note that the typical painting curriculum still discourages the following things that painters— especially young painters—like: 1) decorativeness 2) femininity 3) smaller-scale surfaces 4) narrative graphic art 5) Photoshop. As an art professor I have defended these transgressions. Painting school tells us to “loosen up,” but why shouldn’t we “tighten up”? Painting professors often say that decorativeness is frivolity, but is it? They’ll tell you that big-scale painting is professional—why? They don’t like narratives, but every picture tells a story. They believe that Photoshop is not painting even though anything other than the simplest use of Photoshop requires painting and drawing skills.

Go to art school, but talk back.

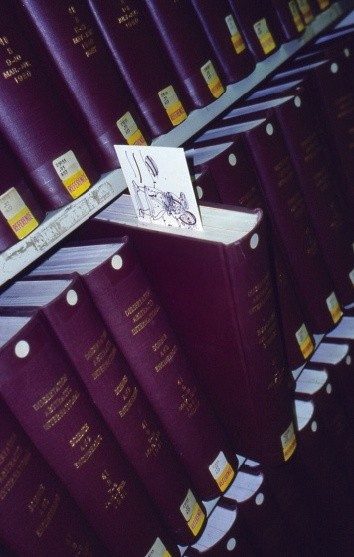

Drawings on file cards hidden in books at the Raymond Fogelman Library (New School, New York), 1997–2005.

As you paint you should read theory. Start with aesthetics, because you already know and practise aesthetics. Everybody has built-in reactions to art. Aesthetic theory reached its apogee in the 18th-century in Kant’s writing. Nobody these days can agree about what Kant meant. For example, Clement Greenberg’s mid-20th-century Kantian assertions have been greeted with skepticism by the philosophers who recently put together the tome Philosophy and Conceptual Art. Claiming that Kant can’t be understood, they believe that Greenberg embodies a special case of misinterpretation.

Greenberg, the learned critic, did, back in the 1940s, what you do now as an inexperienced artist: he judged a painting as good or bad based on his immediate apprehension of it. Such judgements can be made too quickly, and an aesthetic approach to your art that involves not much more than your own personal taste can be limiting, but you should still defend your personal taste even as you read critiques of personal taste, for example by 20th century sociologist Pierre Bourdieu. Discover tastes that you respect but that differ from yours. These tastes are easy to find: ask your mom.

If you are casting about for recent theories about painting why not start with those offered by the organizers of the painting group show that was mounted this past winter at New York’s Museum of Modern Art called “Forever Now: Contemporary Painting In An Atemporal World.” One of the key words in Laura Hoptman’s “Forever Now” thinking is “atemporal,” by which she means our Internet-informed culture in which all of history is available for inspiration. This condition has been talked about since the invention of the telegraph, but more narrowly and slightly more recently in André Malraux’s mid-century “museum without walls” notion that reproductions provide us with endless research material. Postmodern theorists and painters have also been all over this idea for years.

Installation view, detail, “Library Cards,” 2014, 3 x 5-inch mixed media paintings, Halifax Central Library.

Do not become cynical, because you can’t be an artist and be cynical, but you must recognize and even set up your own filters, the way you set up your Instagram filters. Everyone has filters. If museums and magazines and galleries did not have filters they wouldn’t have a mandate or a special place in the world. MoMA, like so many art institutions, has some turf to protect and promote. Established institutions continue what their staffers believe to be a spiritual mandate that refers to their golden years. This happens with moribund results, whether the institution is called The Uffizi or the Museum of Modern Art.

It looks as if MoMA is, on the evidence of “Forever Now,” like so many undergraduate painting programs the world over, interested in mostly gestural abstraction, and so we take note, especially if we do not like gestural abstraction. Gestural abstraction may be part of the MoMA’s legacy, an inheritance of Abstract Expressionism that has become an institutional mandate—a filter—but it also represents one of the most conservative trends in art making today. And by that I mean both aesthetically and politically conservative. I invite you to disagree with me and to think for yourself about this and every other assertion I make.

Although this may be the first painting group show in 30 years at the Museum of Modern Art, you could point out after a little research that there was a very well-received drawing show at MoMA a few years back, a show that reminded us that painters are mostly painter/drawers, and that hiving off painter/painters from painter/ drawers would never occur to a working artist. Again, when you make your paintings please do not feel anxious if they turn out to be drawings. For now it would be best if you stop worrying and get back to painting. I’d advise you to read theory in bursts and then respond, or not, in your art.

Crisis of Lost Faith, 2012, acrylic on MDF board, 5 x 3 inches.

Majorette with No Majorette Sign, 1987, acrylic on Masonite, 5 x 3 inches.

And don’t worry about offending any institution by being critical; no museum staffer is going exclude your work from a show, at least not yet. When you come into prominence as a painter years from now the filters will be different and the theories will have changed. What is atemporal now will soon look like “2015.” Keep painting.❚

Cliff Eyland’s long-term interest in libraries and art resulted in the completion of two recent commissions for public libraries, one in Halifax at the Halifax Central Library and one in Edmonton at the Meadows Library. He lives and works in Winnipeg where he continues to paint and write about art.

Order Issue 135 here.