Les Ramsay

Occasionally, when I am intently immersed in an exhibition of contemporary paintings, I recall something that photo-artist Jeff Wall said during a public talk in Vancouver a few decades ago. Responding to a question about the postmodern dictum that painting was dead, he declared, “Painting isn’t dead, it’s un-dead—it’s vampiric.” I think of his rueful remark—at least, it seemed rueful at the time, and also very funny—because painting persists in a pretty lively, engaged and engaging state well into these most post-postmodern times. If blood is dripping from the fangs of bat-winged, brush-wielding, vampire-like artists, the lifeless bodies of earlier painters strewn about their studios, well, I’m not seeing it.

Based in Vancouver after a few years living on British Columbia’s Sunshine Coast, Les Ramsay has created a series of formally and thematically inventive works including small and medium-sized paintings on canvas, burlap, or upholstery fabric, framed needlepoints and assemblage-like sculptures. On view at the Marion Scott Gallery, they seemed to marry the intuitive and the concept-driven, with influences ranging across folk art, landscape tropes and digital culture. Ramsay’s paintings, particularly, are suggestive of multiple narrative strands and inviting of many creative interpretations.

Les Ramsay, Dusty Ditch at Dusk, 2024, oil on upholstery, 35.56 × 27.94 centimetres. Photos: Byron Dauncey. Courtesy Robert Kardosh Gallery, Vancouver.

The satirically titled Surf & Turf, for instance, a vertically formatted oil painting on canvas, stacks up paired motifs—starfish, wagon wheels and vessels that might signify old-fashioned oil canisters—against a ground of odd abstract forms in bluish grey, powder yellow, leafy green, bright orange and a brown that could be earthy, could be excremental. As gallerist Robert Kardosh has written about the tiers of representational elements in this work, “The entire balancing act is impressively acrobatic but also impossibly unstable.” Ramsay apparently conceived the painting as a critique of colonialism and the environmental destruction dealt by the contemporary descendants of the settler hordes. While the wagon wheels symbolize “westward expansion,” the starfish must allude to the recent and little-understood die-off of the sea star population along the Pacific Coast. And the oil canisters? Well, they readily reference the climatechanging, ocean-acidifying impact of our continuing disastrous dependence upon the internal combustion engine.

Throughout the show, as Kardosh has noted, Ramsay juggles the playful and the sinister, the benign and the menacing. Another of his larger paintings, Night Moves, poses two owls against a cadmium yellow moon, this scene laid upon an unevenly segmented, multicoloured ground. Hybrid creatures and celestial forms, emerging here and there from the quilt-like patches of colour, and a clown-like figure sprawled across the bottom of the canvas evoke land, sea, sky, and undermine human presence. The effect is both comical and unnerving. Read what you will into a work that is initially suggestive of a child’s bedtime story or nursery rhyme but then transmogrifies into an adult’s spooky dream. Or perhaps into late-night, insomniac anxiety about the cosmic joke that is human consciousness.

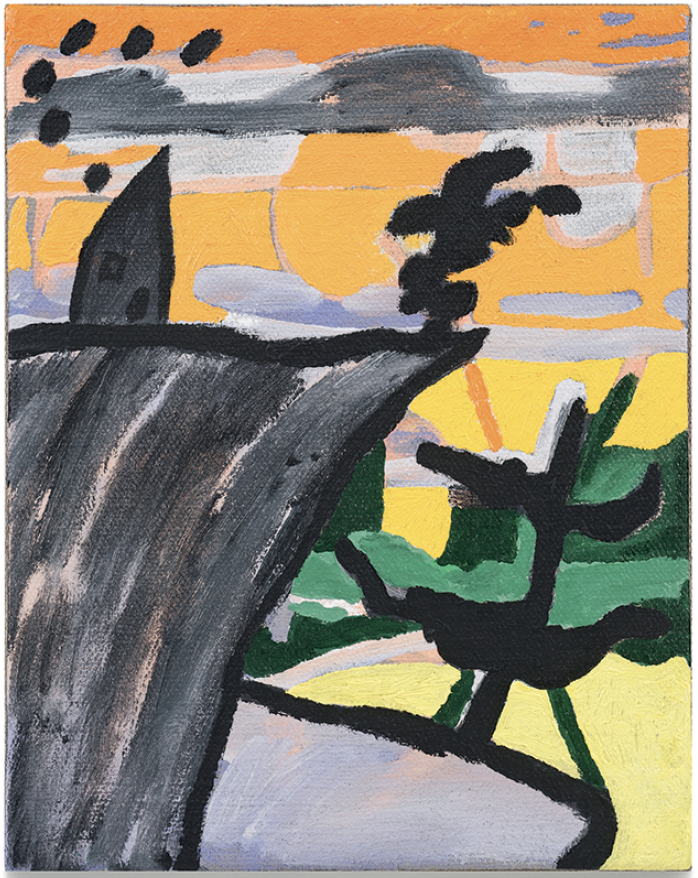

Les Ramsay, Dawn of the Demon, 2024, oil on upholstery, 35.56 × 27.94 centimetres.

Some dozen small paintings, which were installed in a long horizontal row on the gallery’s north wall, strongly compel narrative interpretations, both individually and as a group. Identically sized (14 × 11 inches), vertically formatted and posing elements of high-keyed colour against passages of deepest darkness, they are suggestive of storyboards laying out scenes in a mysterious film or perhaps panels in an underground comic book or zine. Most of these works are divided into thirds horizontally and feature highly reductive—at times almost pictographic—forms that indicate trees, fences, houses, birds and, in one, a curving arrow of a country road disappearing into a backdrop of wonky blue mountains. Despite their charm there is, again, an element of menace here; the potential for disaster is especially apparent in Dusty Ditch at Dusk and Dawn of the Demon in which natural forms and human structures are precariously perched on top of slanting, unstable cliffs. (Note the satanic allusion and titular alliteration.) Even the bright, cheery colours of the plant forms in Helens’ Blackberries are unsettled by the pitch-black night sky behind them.

Ramsay’s two sculptures—assemblages of found and altered elements including driftwood covered with a mixture of sand and acrylic paint, a wooden stool and a pair of stuffed gardening gloves—are part folk-art fancy, part deep-sea grotesque and part ordinary object in the Duchampian process of transformation from banality into art. Two little cross-stitch works employ formal strategies similar to those seen in Ramsay’s small paintings while engaging in this era’s ongoing challenge to the supremacy of “high art” over “craft.”

Les Ramsay, Night Moves, 2021, oil on canvas, 152.4 × 127 centimetres.

Despite the beguiling segues into sculpture and stitchery, Ramsay’s real project here is painting. Last spring, in a public conversation with a younger artist, he spoke about his attraction to the “physical aspect of the painted object”—which in a sense brings us back to that other artist’s talk a few decades ago. Let’s suppose that, for a brief spell, painting had died, that, with high modernism, it had painted itself into a corner of non-existence while alternative art forms, from conceptualism to performance to new media, asserted themselves. The evidence now, however, is that painting has worked its way out of that corner again, out of that formal and conceptual dead end. It seems that applying pigments to a receptive surface—a rectangle of canvas, an altered piece of driftwood, a papyrus scroll, a curving cave wall—persists, just as storytelling does, as a profoundly human impulse. I strongly believe that painting is something our brains, eyes and hands are compelled to do as we attempt to make sense of the world, to create meaning and to connect with one another.

Not that I’m unreservedly optimistic about the future of painting because, who knows? Maybe it’s AI rather than postmodernism that is going to finish off— to render obsolete—the acts of art making that for so many millennia have defined us as human. ❚

“Les Ramsay: Velvet Morning Light” was exhibited at Marion Scott Gallery (now the Robert Kardosh Gallery), Vancouver, from May 25, 2024, to June 15, 2024.

Robin Laurence is an independent writer, critic and curator based in Vancouver.