“Leonardo da Vinci: The Mechanics of Man” and “Visceral Bodies”

An air of reverence attended “Leonardo da Vinci: The Mechanics of Man”—and why not? Much as postmodern art and theory have challenged the historical canon, Leonardo was, and remains, an undeniable genius. And that’s not because he created two of the Western world’s most famous paintings. (It could be argued that, fine as it was, painting was among the least of Leonardo’s accomplishments.) No, what was and remains so compelling about him is his extraordinary draftsmanship in the service of his endlessly observant and inventive mind. His investigations into architecture, engineering, cartography, even (regrettably) the machinery of war, are perfectly complemented by his close studies of the natural world and the human form. As seen in the Vancouver Art Gallery’s exhibition of Leonardo’s anatomical drawings, borrowed from the Royal Collection, Windsor, his intellectual curiosity and powers of observation were brilliantly met by his expressive abilities. Hand, mind and eye worked together in exquisite harmony.

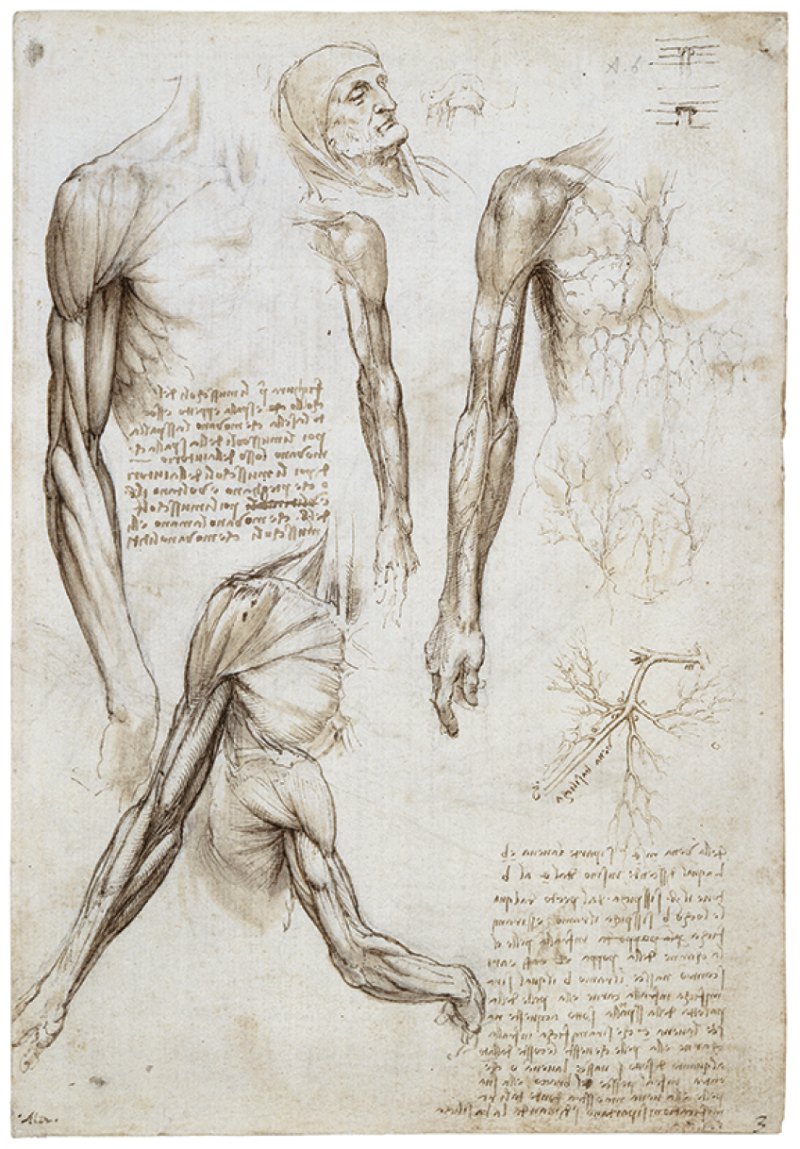

The 18 sheets of ink drawings, made during the winter of 1510–11, were intended by Leonardo to be published in a treatise on anatomy. The publication, however, wasn’t realized, and the works fell into some obscurity. (The project stalled partly because Leonardo’s anatomist died of the plague and partly because, as VAG senior curator Ian Thom has commented, there were no printmakers in that time and place adequate to the task of reproducing the extraordinary detail and groundbreaking realism of these drawings.) Acquired by the Royal Collection about 1660, they only recently have been fully appreciated as what surely must be the most beautiful anatomical drawings ever created. The bones and tendons of the hand and foot, the veins of the arm and the trunk, the delicately peeled away muscles of the face, all are rendered with an extraordinary degree of skill and finesse.

Leonardo da Vinci, folio 3r, The throat, and the muscles of the leg, 1510–1511, pen and ink with wash, over traces of black chalk; red chalk sketch at top right, 29.0 x 19.6 cm. Courtesy The Royal Collection © 2009 Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II.

The result of a series of dissections undertaken in Milan when the artist was 58, these works reveal his driving desire to understand the human body within the context of observed nature rather than religious belief. The acuity of Leonardo’s vision and the accuracy of his execution, along with his accompanying notes (written in mirror fashion, in Italian rather than Latin), contributed to his tidy disposal of pre-existing notions of how human beings are put together. “The eye,” Leonardo wrote, “is the chief means by which the mind can most completely and magnificently comprehend the infinite works of nature.”

Leonardo’s eye, as it turns out, was a few hundred years in advance of his time—meaning that these double-sided drawings, with their careful and, in some places, copious notes forming an intriguing network of lines and jots, were unique in their age for comprehensiveness and draftsmanship. For instance, the catalogue describes Leonardo’s drawings of the vertebral column as “the first accurate depiction of the spine in human history.” Five hundred years later, “no artist or anatomical illustrator has surpassed Leonardo’s accomplishment.” During a media tour of the show, Royal Collection curator Martin Clayton repeated the claim that, given how true they are to their subject, Leonardo’s drawings of the hand and foot would still be effective learning tools in today’s anatomy classrooms and labs.

Scientific accuracy notwithstanding, it was interesting to see the persistence of what we recognize as Leonardo’s style through his various rendered layers of dissected humanity. His fine, confident line and the classicist manner in which he depicts facial features, for instance, or noses and chins in profile, remain distinctive. It’s also interesting to contemplate the anatomical works in the context of the artist’s more widely known drawings of male nudes, portrait heads, and exaggerated and sometimes grotesque faces and expressions. Clearly, the human subject was fascinating to him, in the extremes of life as well as the rigours of death.

Leonardo da Vinci, folio 6r, The muscles of the arm, and the veins of the arm and trunk, 1510–1511, pen and ink with wash, over traces of black chalk, 28.9 x 19.9 cm. Courtesy The Royal Collection © 2009 Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II.

In its text panels and adjunct displays, the exhibition demonstrated the ways Leonardo da Vinci could be the poster boy for Renaissance humanism and an empirical approach to science and learning. Among the show’s quotes was this from the artist: “Those sciences that are not born of experience, mother of all certainty, are vain and full of errors.” It’s illuminating to consider the optimistic convictions of the proto-modern past, as demonstrated by Leonardo’s words and drawings, against the pessimism and uncertainty of the postmodern present. And this consideration is exactly what the vag achieved in organizing the group show “Visceral Bodies” to share the gallery’s main floor with “The Mechanics of Man.”

As seen throughout the “Visceral Bodies” survey of recent and contemporary images of the human body, artists now operate in a state of considerable doubt and apprehension. Ours is a time when every established system of observation, every form of evaluation and every particle of knowledge appear to be tainted by biases of gender, culture and sexual orientation. Far from endorsing the idea that experience is “the mother of all certainty,” contemporary artists are stranded in a state of motherless uncertainty. Paradoxically, as the show and catalogue also demonstrated, the other side of this condition is the vast expansion of our knowledge of the workings of the human body through new medical imaging technologies.

“Visceral Bodies” represented some 20 international artists working across many media, including sculpture, drawing, painting, photography, video, sound and even lithography. Staid as this list appears, a mood of provocation and a strategy of shock, revulsion or implied violence informed much of the work. Just as Leonardo’s peers may have found the idea of human dissection disturbing, we are confronted with our own squeamishness in the face of Magnus Wallin’s prosthetic eyes or Mona Hatoum’s endoscopic images of the inside of her body or—most markedly—Teresa Margolles’s records of autopsies. Margolles presented us with the sounds of a corpse being cut open and with splatters of human matter—fluids leaked from a body during autopsy and caught on a kind of Plexiglas vitrine. Her strategies forced our awareness past the ick response and towards the social factors that inform the daily forensic operations of a Guadalajara morgue. In this morgue, the site of much of her art, victims of violent crime may briefly repose before being subjected to another kind of violence—dissections in the service of some dubious idea of justice.

Kiki Smith, Untitled, 1991, ink on Gampi paper in four parts, life size. Courtesy The Broad Art Foundation, Santa Monica.

Violence is explicit in Berlinde De Bruyckere’s two disturbingly beautiful drawings Schmerzensmann 2 and 4, images of torture, perhaps, or martyrdom, and in Kiki Smith’s untitled 1991 life-size sculpture of a dismembered and beheaded man. Created out of crumpled paper and covered with blood-red ink, then hung on the wall like pieces of meat on hooks in a butcher shop, Smith’s flayed and mutilated figure speaks not only to the theme of dissection established by the Leonardo show but also to the human body as the site of trauma, of the brutal acts—war, terrorism and, again, torture—of humankind.

A more indirect kind of violence, along with viscerality and vulnerability, is suggested in Shelagh Keeley’s Writing on the Body, a multi-panel wall drawing executed in Tokyo in 1988 and now part of the vag’s permanent collection. Eloquent renderings of bodies and body parts—adults and children, male and female, fully fleshed and skeletalized—are strewn across a ground smeared with blood-red and urine-yellow pigment and scrawled with body-referenced words and phrases. In this big and moving work, Keeley reflects feminist thinking of the 1970s and ’80s: that the body is a scroll on which are written the annals of history, science and culture. Through this work, too, she mourns the vast and the particular: the global AIDS crisis and the loss of a friend to that desperate disease.

Luanne Martineau’s Dangler, a felted fabric sculpture suspended from the ceiling, also takes the body apart in violent and disturbing ways, even as it reclaims what curator Daina Augaitis describes as “devalued craft-based techniques.” With its torn-apart breasts and suggestions of disembowelment, the work evokes the victim of a bomb blast; at the same time, its streaming and tumbling strands and clots of colour could allude to painting and its deconstruction. There is something compellingly contradictory about this work, too, as Martineau conjoins comic-book grotesquerie—a detached smile hovers above the mutilated body—with the gentle work of the hand, the felted and braided components of this outrageous art.

David Altmejd, Untitled, 2008, wood, foam, plaster, burlap, metal wire, paint. Photograph: Jeremy Lawson. Courtesy Andrea Rosen Gallery, New York. Courtesy the Brant Foundation, Inc. USA. © David Altmejd.

A number of gifted men were also represented in “Visceral Bodies,” among them Marc Quinn, Gabriel de la Mora, Antony Gormley and David Altmejd. The women artists, however, seemed to best redress the historical imbalance posed by both the title and content of the Leonardo show. It’s a distressing reality, however, that centuries of patriarchy and man-centered art making were countered by such a tragic view of the contemporary human condition. ❚

“Leonardo da Vinci: The Mechanics of Man” was exhibited at the Vancouver Art Gallery from February 6 to May 2, 2010. “Visceral Bodies” was exhibited at the Vancouver Art Gallery from February 6 to May 16, 2010.

Robin Laurence is a writer, curator and a Contributing Editor to Border Crossings from Vancouver.