Leon Golub

Some values typically not associated with 82-year-old men: edginess, muscular thinking, serious fun, hotness. Sure, Americans obsess over youth, sex and death more than many: you need only think of the current rash of vampire entertainments. But all nations get to suffer more or less equally when it comes to the spectacular lack of thoughtful discourse on bodies, excepting in matters of trade.

Enter American painter Leon Golub, who died in 2004 at 82 and whose critical engagement with power and embodiment over 60-odd years demonstrates an awe-inspiring consistency of vision and complaint. More recently, though, the 43 oil-stick, ink and acrylic drawings on view at The Drawing Center in New York—all made during the last five years of his life—continue to kick against the pricks. More, they do so with a vitality of thought, scale, gestural effect and colour that belies any conventional understanding of old age, late art and, indeed, aspects of liveness in visual art. “Live & Die Like a Lion?” was, for me, a bright flare in a season shaped more by hyperbole and empire building, as evidenced in exhibitions by Tino Seghal and Marina Abramović.

Leon Golub, LIVE & DIE LIKE A LION?, 2002, oil stick on Bristol, 8 x 10”. Photograph: Cathy Carver. Collection of Anthony and Judith Seraphin, Seraphin Gallery Philadelphia, PA. Art © Estate of Leon Golub/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY. Photographs courtesy The Drawing Center, New York.

Working in small scale on universal themes, Golub demonstrates a gleeful play of expression, perhaps unprecedented, yet certainly in keeping with the arc of his career. Using eight-by-ten panels of bristol board or vellum, he makes backgrounds first: streaks and smears of colour, the excess paint scraped away, leaving bright, pocked fields on which to draw figures, mostly adrift in space, with great speed and energy. These images really move, from colour to line to biting commentary. A drawing from 2002 from which the exhibition takes its name is exemplary: set against a white background, bound by a red streak below and above, a blue lion advances, giving us a sidelong glance. Beneath his torso, a black line seems to threaten both creature and viewer: an extension of the penis, a cane or a club?

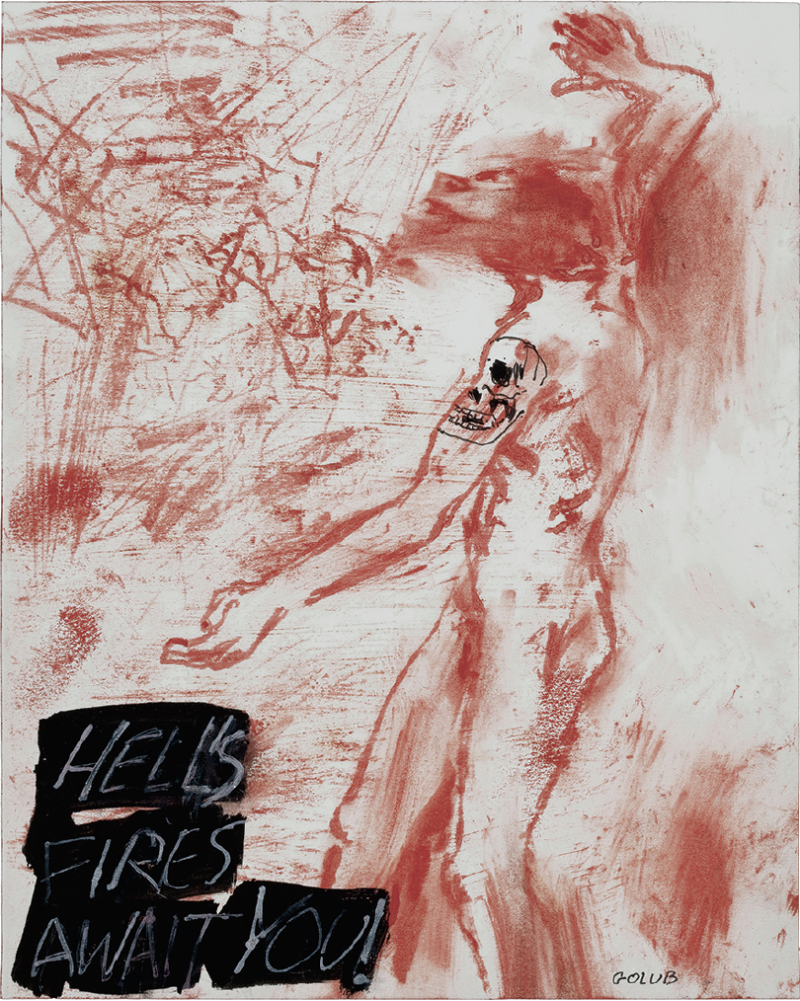

Golub writes the title, with question mark, over a red band of colour at the bottom of the drawing, casting a pall over the notion of “living” or “dying” like a lion. Death makes mice of us all, ha! There is overall a sense of grafitti-like urgency throughout the exhibition, wherein titles and bits of text send messages ranging from the poetic to the ironic on the themes of sex, death, violence and art. In an interview with Border Crossings, Golub noted that these “are like the final stroke to make the thing go where I want it to go.” The words do take you places, and though the relationship between text and image is often quite literal, there are enough gaps to incite mental wandering.

Lions and dogs reappear through- out the show, acting as thematic bridges between images grappling with mortality, violence and sex. At once apocalyptic and carefully rendered—somehow looking more honourable than humans—the animals clarify the social and political aspect of the images on view. Where the smaller scale and the sense of human figures, alone and adrift, tends to convey greater interiority, the animals underscore the heroic dimension, the sense of history writ large. If the dogs seem like us, all thoughtful eye and survival instinct, they remind us too of the particularity of our species, bound by primitive urges and intellectual power.

Leon Golub, HELL’S FIRES WAIT YOU!, 2003, oil stick, acrylic and ink on Bristol, 10 x 8”. Photograph: Cathy Carver. Courtesy Ronald Feldman Fine Arts, New York. Art © Estate of Leon Golub/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY.

Images of death jump easily from personal to political. Fuck Death, 1999, for instance, shows a vivid purple skull looking upward, bound by the words of the title. Here’s To You Pal!, 2002, depicts a blue skeleton falling through space, arm extended upward or else, perhaps, rolling on the floor laughing. Countering this kind of cheeky attitude, In the Barbed Wire Cosmos, 2004, shows a blue figure—crawling or swimming?—behind a wire fence, mouth and eyes stylized gashes, unavailable to us in torment. The fence is part interment camp, part wedge between the image and our understanding of it. The social wallop lies in the palpable sense of camps as continuums—from huge refugee centres to Guantanamo, they remain with us—and in the despair mirrored in the face of the drawn figure.

Similarly, sexualized imagery walks the line between private and public. Come On!, 2003, is a naked woman, legs apart, elbows bent and fists clenched: boxer, stripper, rock star. You Son of a Bitch, 2003, shows a woman, bent over, one hand approaching her cheek, as if feeling a blow, the other hand reaching for or dropping a gun. The ambiguity of this imagery—hero or victim, cartoon or commentary—requires us to till the darker corners of our own experience to find meaning. Other images depict naked couples in the act and men drawn as satyrs; often, one or more figures seem to confront the viewer directly with their gaze. But whereas bodies are mostly rendered with care, facial expressions tend to distort—crudely drawn mouths pout, grimace or sneer, heads lose focus and decompose into pools of colour. Flesh rules, unabashedly, says Golub. Right on! Watch out!

Golub is perhaps best known for the large-scale paintings he made during the 1980s in which violent scenes involving soldiers, gangs, torturers painted on unstretched linen acquired an elegiac aspect. But the move to miniaturize cannot be explained alone by an elder artist’s need for a less physically exhausting process. These drawings do not overwhelm: they stare us down, command our attention, draw us in, thumb their noses. Intimate, sexy, pissed off, fun, the small drawings suggest the extent to which matters of social justice dominated the artist’s daily habit and world view. More, with their emphasis on isolated figures reacting to unshown situations, they emphasize the role of ordinary life in the political field and perform miniature dramas for the solo viewer roaming on hardwood floors. ❚

“Leon Golub: Live & Die Like a Lion?” was exhibited at The Drawing Centre in New York from April 23 to July 23, 2010.

M J Thompson is a writer living in Brooklyn and Montreal.