Lee Friedlander

There is something delightfully perverse about Lee Friedlander’s photographs. Look at his images of the Canadian Rockies, for instance. Instead of shooting the landscape in all its obvious geological magnificence—calling up the romantic sublime and making comparisons between our brief little lives and the awe-inspiring age and scale of the mountains around us—the New York-based artist focuses on scruffy undergrowth and scrawny young trees. Foliage is used not to enhance what we understand to be natural beauty but to obscure and confound it. If we are actually permitted a glimpse of a mountain, lake or glacier-fed river, it is through an unattractive screen of needles and branches. As is true of so many of Friedlander’s black and white photos, shot mostly with a 35-mm camera, conventions of framing and focus and notions of the picturesque are turned inside-out and upside-down.

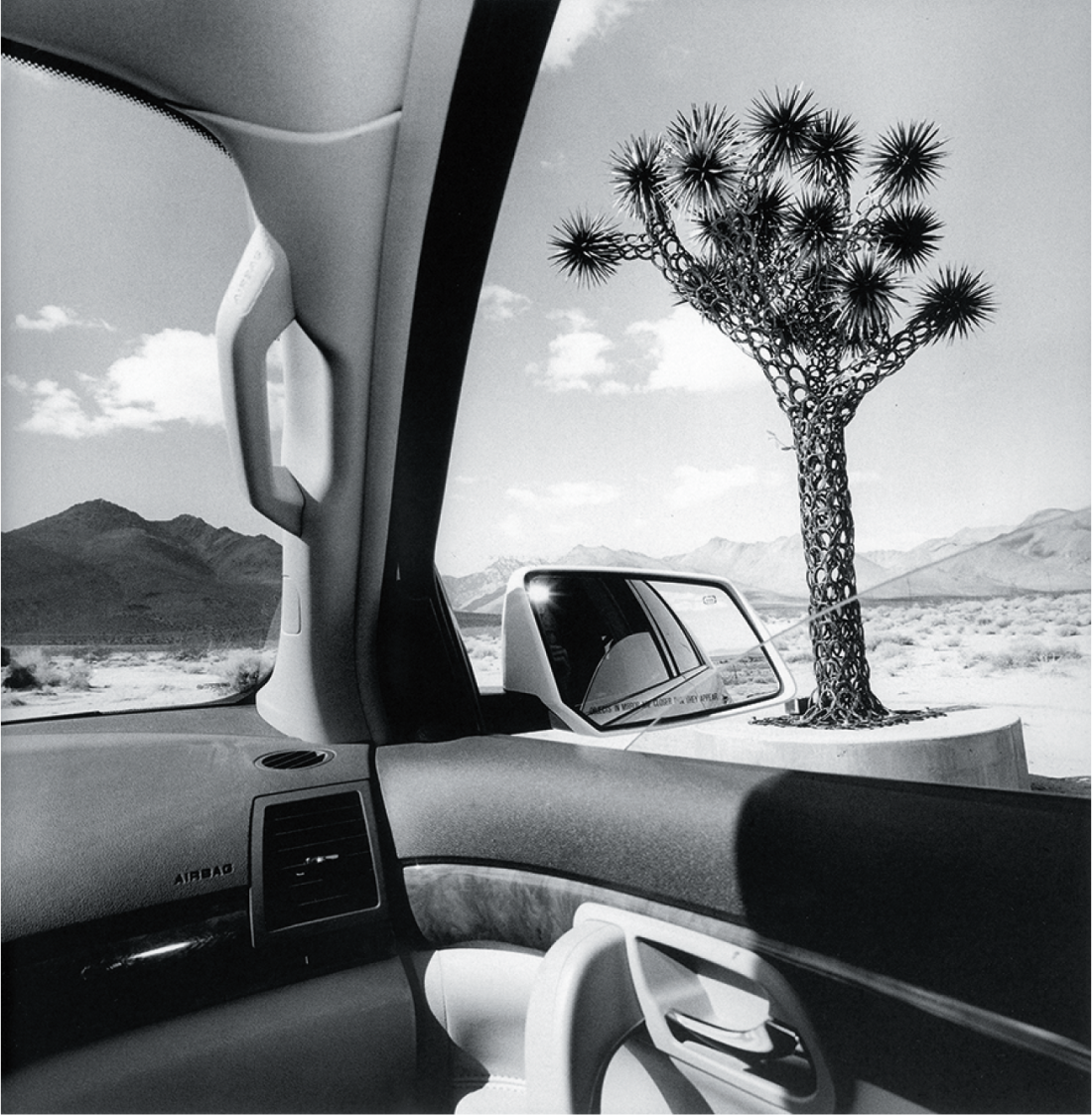

Lee Friedlander, California, 2008, gelatin silver print, 38.5 x 37.8 cm. Courtesy Artworkers Retirement Society and Presentation House Gallery, Vancouver.

Most of the photos on view at Presentation House Gallery were borrowed from an unnamed private collector; curiously, their presence here represented the first major exhibition of Friedlander’s work in Canada in decades. Gelatin silver prints were complemented by magazines (including a 1985 Playboy featuring Friedlander’s 1979–80 images of a nude Madonna, young, dark-haired and supplementing her pre-fame existence by working as a photographer’s model); a portfolio of photogravures (“The American Monument” series); and a selection from the 40-plus books of photos the immensely prolific Friedlander has published over the years. Spanning five decades of his career, the exhibition brought our attention to what curator Helga Pakasaar described in the accompanying text as his “eccentricities of the commonplace.” Friedlander’s “fragmented compositions,” she observed, “are full of obstructions, glitches, reflections and interruptions.” He belongs to a generation of Modernists that flips and trips the vaunted and the obvious, imaging instead the banal and the unexpected. Although Friedlander has long been associated with what he calls the “social landscape”—urban scenes that range from the shadows cast by stop signs at deserted intersections to mannequins in store windows to hotel rooms lit by television screens entirely filled by ghostly human faces—he has also made photographs of road trips through rural landscapes and of factory workers in the American Midwest. He has explored, too, the still life, the nude and the self-portrait—familiar genres treated in unfamiliar ways. He often works in series that may extend over years and even decades and despite the early influence of Walker Evans and Robert Frank, he has landed on an entirely distinctive register of contemporary American life and values.

In the 1976 “American Monument” series, Friedlander focuses mostly on overlooked or overwhelmed public statuary, such as a bust of John F Kennedy on a street in Nashua, New Hampshire, utterly disregarded by the shoppers walking past, and a sculpture of Theodore Roosevelt on horseback in an unpeopled park in Minot, North Dakota. Friedlander shot this work from behind, at a distance and, again, through a mesh of foliage. (And yes, we are effectively looking at a horse’s ass, a somewhat cynical way of remembering the president who did so much to champion and expand national parks and forests in the United States.) Also part of the “American Monument” series, Mount Rushmore is seen indirectly, as a reflection in the windowed wall of a visitors’ centre. Standing in front of that reflection are two aging tourists, he with a camera in front of his face and the strap of a binoculars case slung over his shoulder, she with binoculars over her eyes and a purse hung on her shoulder. Long before our lives were entirely mediated by handheld digital devices, Friedlander made explicit the second-hand and consumerist nature of the touristic experience, the main attraction viewed by others—and by us—through a series of lenses and reflections.

Lee Friedlander, Mount Rushmore, South Dakota, 1969, gelatin silver print, 20.5 x 30.8 cm, from the publication, The American Monument, 1971. Courtesy Presentation House Gallery.

In Blush, Sweat and Tears, taken for The New York Times Magazine during New York fashion week in 2006, Friedlander’s camera is aimed at the frantic, backstage labours of dressers, hairdressers and make-up artists. He completely eschews the glamour and the glitz—the clothes, the designers, the catwalk down the runway, the celebrities in the audience—for the hard-working technicians of production and display. With Friedlander behind the curtain, living models are reduced to mannequins, static and expressionless, awaiting animation by the beings we recognize as more fully human, the workers with whom we can actually identify. Again, spectacle is undermined, conventions flipped, expectations thwarted.

Friedlander’s fascination with both reflections and display is fully manifested in his “Mannequins” series, shot in New York City, San Francisco, Tucson and Newport, Rhode Island in 2010–11. Here he creates often surreal and collage-like images, not by physically pasting elements together but by finding ways for his camera to catch multiple reflections from the store windows behind which the mannequins stand. What results are fragments of clothing and humanoid forms overlaid with shards of the urban environment—buildings, streets, cars, pedestrians. In many of these photos there is evidence of the disjunct, the absurd, the incongruous. Attempts at glamour are juxtaposed with and undermined by the banal, although in some photos, the low-end mannequins and the garments they display fully assume the weight of banality on their own, without any further insinuation from the reflected world around them. Pakasaar deftly sums up Friedlander’s work with the observation that he is “fuelled by an ironic scepticism” but nevertheless “maintains a strong affection for the stubborn nature of reality.” ❚

“Lee Friedlander: Thick of Things” was exhibited at Presentation House Gallery, Vancouver, from November 29, 2014 to February 8, 2015.

Robin Laurence is a Vancouver-based writer, curator and Contributing Editor to Border Crossings.