Laura Kikauka

Laura Kikauka likes stuff. Lots of stuff. Brightly coloured, discarded, cheap, weird, outmoded stuff. The Hamilton, Ontario, born artist pursues a practice that finds an eccentric beauty in what some would consider tacky and garish. But underneath the cheeky humour of her work is a serious critique of our wasteful consumer society and questions about how we assign value to objects, what constitutes good taste and bad taste, and what qualifies as high art as opposed to low art.

Kikauka divides her time between the Funny Farm West in Meaford, Ontario, and the Funny Farm East in Berlin, the “farms” being less homes than constantly morphing installations. Photos of them show themed and colour-coded rooms containing shelves lined with tourist souvenirs and vintage novelty gifts, floors tiled with vinyl records, ceilings strung with tiki lamps and furniture trimmed in fun-fur fringes. At the Power Plant in 2004, audiences got a taste of what living in one of the Funny Farms would feel like. For that exhibition, Kikauka brought together enormous amounts of obsolete electronic gadgets, toys, anonymously produced crafts, household items and food packaging. The installation filled to nearly overflowing a good portion of the gallery’s cavernous first floor. At first it seemed chaotic but, for this viewer wandering through, a sense of orderliness emerged. Objects were sorted by colour or some other common feature. In a profile in C Magazine, Summer 2007, Kikauka said there is “never enough” sorting and recombining of objects, making the process an important element of her practice. Just as important as the art-as-labour aspect is how Kikauka’s installations confront viewers with objects that pose questions such as: Why did someone think producing this item was a good idea? To whom was some of this junk meant to appeal? And how long would it have taken, had Kikauka not intervened, until all of it ended up in a landfill? It is this intervention on Kikauka’s part that prompts viewers to think about taste and what constitutes an object’s intrinsic worth.

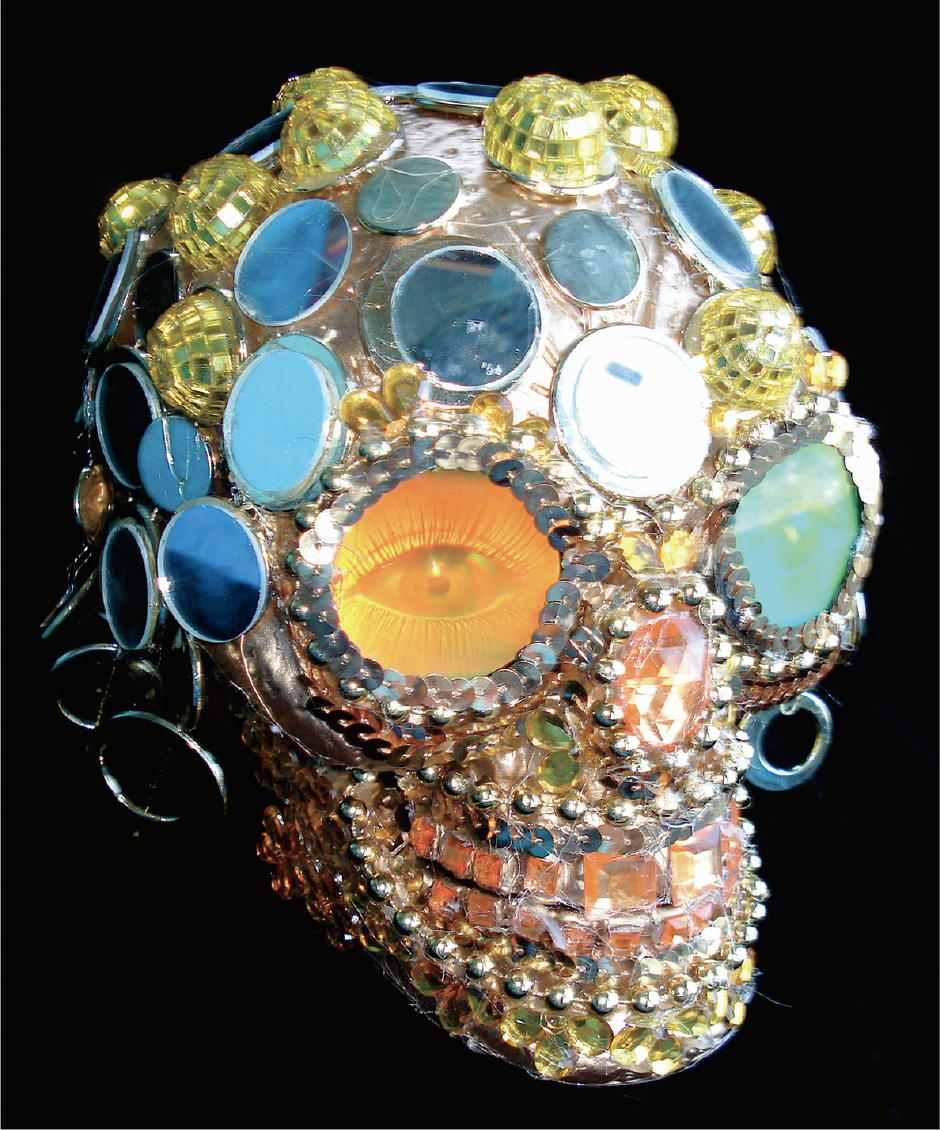

Laura Kikauka, Silence is Golden, 2009, mixed media, 20 x 16 x 24 cm. Courtesy Laura Kikauka and MKG127.

Kikauka’s installations, apparently influenced by 1960s American Pop art—Oldenburg’s The Store comes to mind or the work of artists like Paul McCarthy and Mike Kelley—they also refer to the much older European tradition of the Wunderkammer. Constructing these “cabinets of curiosities” was a popular aristocratic hobby beginning in the 16th century, meant to impress by containing an array of rare, expensive and unusual items. In this most recent exhibition, “For the Love of Gaud (Damien’s Worst),” Kikauka took the notion of the Wunderkammer and turned it on its head.

Sculptures of heads or, rather, skulls—dozens of them lining the gallery walls—made up the installation at MKG127. They were a tongue-in-cheek riposte of British art star Damien Hirst’s platinum-cast and diamond-encrusted skull, For the Love of God, 2007, which has become an icon of the spectacle-driven, inflated global art market of the past 10 years. Unlike Hirst’s immaculate creation, however, Kikauka’s skulls, festooned with mirrored discs, faux gems, and plastic baubles and beads, betray the hand of their maker with lopsided eye sockets, visible strands of hot glue and wonky teeth. Some functioned as tabletop-sized lamps, which returned the use value to some of the bric-a-brac. Kikauka even picked up on Hirst’s word play by giving the sculptures titles such as Blue by You or Vertigo-a-Go-Go.

Taken as a whole, the installation felt like a combination of a carnival haunted house, Goth dance club and a craft fair organized by Wednesday Addams. Eye-popping fun aside, the skulls also raised questions about what should be, as opposed to what is, considered when assigning value to artworks. Is it the technical skill of the artist evident in the execution of a work that makes it valuable or the concept? Is it the amount of time involved in its making or the materials used? Is it supply and demand, the amount of pleasure it gives when looking at it, positive reactions from art critics, previous auction records or the recognition-factor of the artist’s name?

The answers to questions of art’s monetary value will vary depending on who you ask and their place in the art world; Kikauka, by making art that could easily but erroneously be dismissed as simple kitsch, doesn’t seem concerned with what the answers are. She’s too busy sorting through piles of trash, looking for things she can turn into quirky treasures. ❚

“For the Love of Gaud (Damien’s Worst)” was exhibited at MKG127 in Toronto from September 12 to October 10, 2009.

Bill Clarke is a Toronto-based visual arts writer and the Executive Editor of Magenta Magazine, an online visual arts journal.