Larry Glawson

The work of Larry Glawson has always been a quiet response to the Modernist idea that creativity and domesticity are inherent enemies. In this revealing retrospective of Glawson’s photography, curator J J Kegan McFadden hits on a way of tying together 27 pieces that span three decades and six distinct bodies of work. All of the images—from a casual, candid snapshot in 1979 to a large-scale digitally manipulated nude portrait in 2010—centre on one subject: Glawson’s long-time partner, the artist and writer Doug Melnyk.

More than a clever organizing principle, this approach actually goes to the heart of Glawson’s oeuvre, which is the rich, unpredictable connection between everyday life and art. Moving between home and work, between the mundane and the sneakily sublime, the veteran Winnipeg artist explores the ways in which deeply personal matters—identity, affiliation, love—are publicly presented through photography.

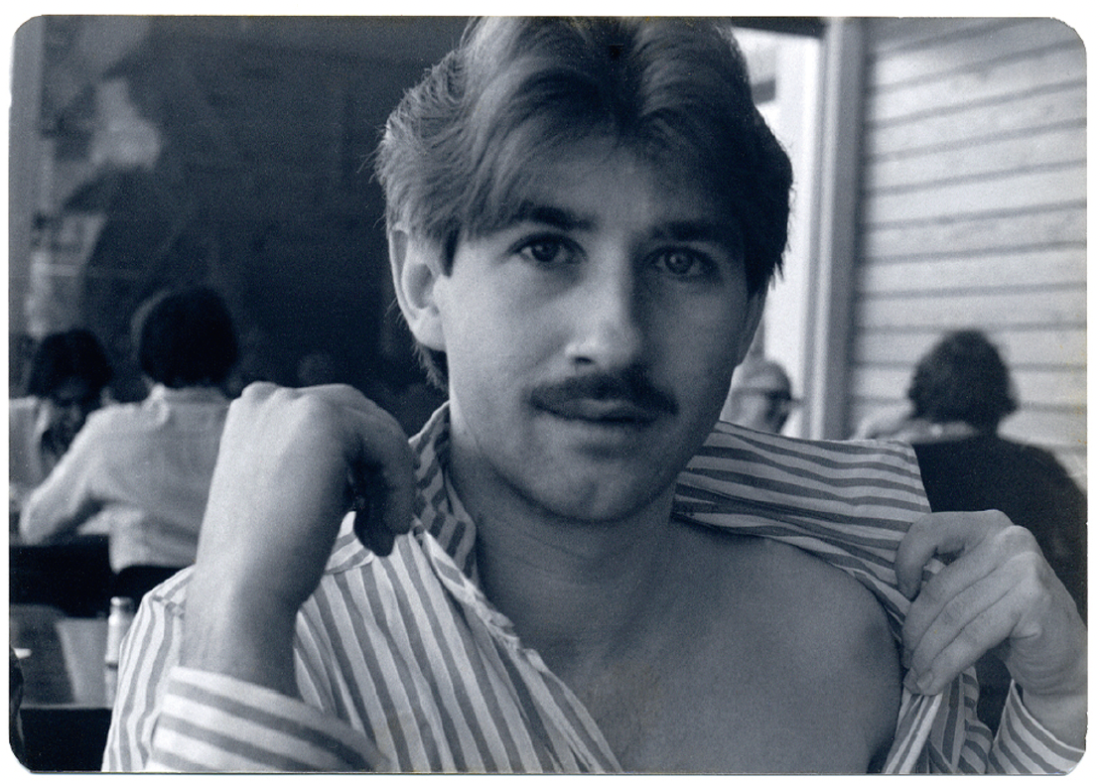

Larry Glawson, Untitled (Doug showing hickey), 1979, black-and-white silver print, 3.5 x 5”. Collection of the artist. Courtesy the artist.

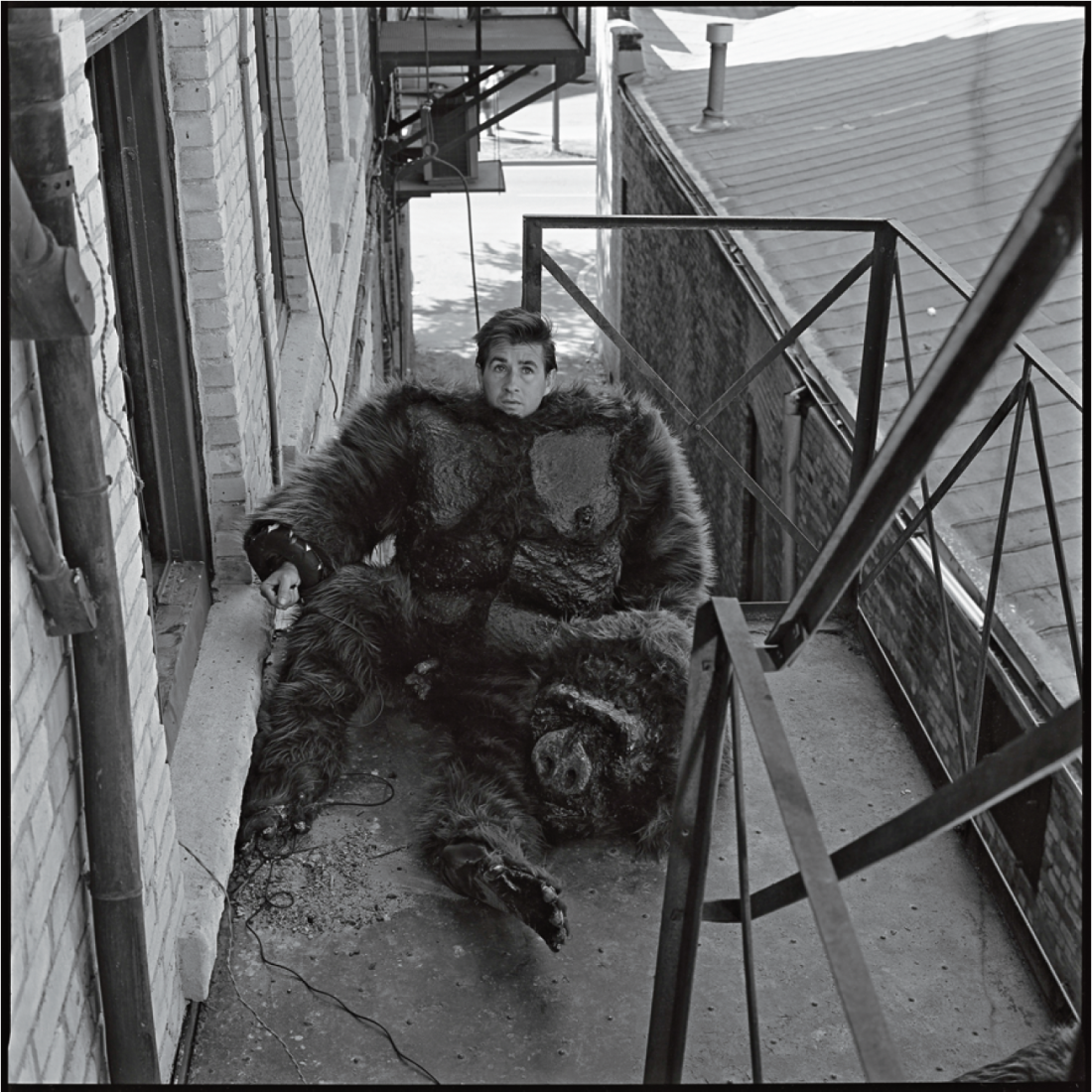

With his expressive body language and endearing face, Melnyk is a dream subject, whether he’s theatrically posed or seemingly unaware, standing on the dock at the family cottage or dressed in a gorilla suit. Melnyk’s role as Glawson’s recurring motif is poignant: he’s caught at photography’s paradoxical junction of the instantaneous and the everlasting. A single image may freeze him as heartbreakingly young: we first see Melnyk as a skinny kid with feathered hair and a quintessentially ’70s moustache in Untitled (Doug showing hickey). Taken together, though, the photographs reveal the gradual encroachments of time and age. In one of the most recent works—taken from the significantly titled series “home bodies”—Melnyk is standing naked in the living room of the apartment he shares with Glawson. In the half-caressing pose of one of Michelangelo’s slaves, he is now defiantly middle aged.

Glawson’s photographs often invite us into the living room. Domesticity is under-represented in art, gay domesticity even more so, and curator McFadden clearly views the work as a queer re-visioning of the family album. (The exhibition’s title is a riff on “27 X Sonia: Portraits by Walter Gramatté,” a 1992 show at the University of Winnipeg’s Gallery 1C03 that featured 27 images of the musician Sonia Eckhardt-Gramatté by her first husband, a German Expressionist painter and printmaker.) In this context, the details of homeyness—hockey socks, potted plants, mussed bed sheets warm from sleep, an unfinished paint job, the mysterious lives of the couple’s cats and dogs—take on heft.

Of course, these images are more than family snaps. Glawson’s work may be intimate, but it never falls into familiarity. Objects and people sometimes seem stranded between the utterly ordinary and the suddenly strange. In Untitled (Doug with Amanda’s clogs) from 1984, Melnyk is dressed in a bathing suit and laden down with a small niece’s random beach stuff—Popsicle wrapper, shoes, towel. The photo is subtly aestheticized, though, so that Melnyk seems to be parting the clouds that surge dramatically toward the image’s edges. In Untitled (Doug with Lucy in the field) from 1993, Melnyk stands in the bush dressed in pyjamas and rubber boots, waiting for a sheepish Chihuahua to do her business. It’s a familiar, even comic scene, but the silvery night lighting, the discrepancies in scale, the remote point of view, imbue it with enigmatic atmosphere.

Larry Glawson, Doug in Gorilla Costume, 1986, black-and-white silver print, 30 x 30”. From the “Self Portraits Project.” Collection of Dave Grywinski. Courtesy the artist.

Glawson, who has also had a long career as a teacher and arts administrator, moves from old-school black and white to big, punchy C-prints, to digital stitch-ups and video-still collages in this exhibition, for a succinct recap of recent developments in photographic technologies. More than that, though, this show confirms Glawson’s patient, clear-eyed testing of the medium’s limits, and in this project, his work succeeds precisely because it is not afraid of failure. Glawson is often more interested in what a photograph doesn’t tell. He checks to see where the relationship between photographer and subject strains, where the temporal and spatial gaps show through.

November 30 1989, sheet 4 #14, sheet 1 #17 is a double portrait of Glawson and Melnyk. The two men seem to be standing together, but in fact they were shot at different times in the same corner of the apartment, the two images then fused together. The barely perceptible fractures suggest the delicate line between separateness and togetherness in the give-and-take of a long love affair or an extended creative collaboration. In this subtle and lovely twinned image, Glawson’s life and art come together. ❚

“27 X Doug: Portraits by Larry Glawson,” curated by J J Kegan McFadden, was exhibited at Gallery One One One in Winnipeg from July 19 to September 17, 2010.

Alison Gillmor is the Pop culture columnist for the Winnipeg Free Press and often writes on visual arts and film.