“Kurelek: A Biography” by Patricia Morley

There is an apocryphal story, variously credited, of an eight-year-old asked to review a book about penguins for the Christmas issue of a journal. The young reviewer began: “This book taught me a great deal more about penguins than I care to know.” Anyone reading Patricia Morley’s biography of Kurelek will sympathize.

Quite simply, the Kurelek described by Morley is a monster. He is vain to the point of megalomania, ingratiating but ungrateful, narrow, authoritarian and mean-spirited, a poseur and a posturer, crafty with a peasant cunning, full of false humility and self-serving braggadocio, obsessive, secretive and vindictive. In short, not the sort of man you’d want to invite to dinner, as several would-be friends apparently discovered, to their dismay. This may or may not be the real Kurelek, and there are some who, it seems, found him quite delightful, but the overwhelming impression of Kurelek in the book is negative. If he were alive today, I don’t think he’d ask Patricia Morley to call him “Bill.”

Which she does. Through some bizarre notion of good-fellowship, Morley refers to Kurelek throughout the text as “Bill,” taking the book out of the realm of academic scholarship and placing it squarely in the tradition of amateur history. The style is made even more clunky by Morley’s habit of referring to the future as if she were a 19th-century novelist. “They would bear fruit in times to come,” she tells us, speaking of the attitudes of some of Kurelek’s friends. She describes a message in a trompe-l’oeil and asks rhetorically, “Did Bill have a personal antagonist in mind?” I cringed, expecting at any moment to be addressed as “dear and gentle reader.”

The facts of Kurelek’s life are well known. He was born in Alberta but grew up in Manitoba near Stonewall. When his parents moved to Ontario, he followed, though by then he was an adult. By all accounts, his youth as the son of a Ukrainian pioneer farmer was perfectly typical, although Kurelek developed a love-hatred relationship with his father which affected him for the rest of his life and which he exploited in his work. After unsuccessful attempts at art schools, where he was unable to find the “master” he sought, Kurelek moved to England. There, he learned his trade as a picture-framer and entered into psychoanalysis. He painted some of his most interesting work as part of a program of art therapy, strange paintings full of violence and self-flagellation, rooted aesthetically in the work of Breughel and Bosch. He underwent a religious crisis from which he emerged as a right-wing Catholic, committed to what he himself described as religious propaganda art. He returned to Canada where he developed a fruitful relationship with the Isaacs Gallery. He began to turn out the paintings of the prairie west (sometimes two or three a day) which established his reputation and made him one of the most sought-after artists in Canada. He died of cancer in 1977.

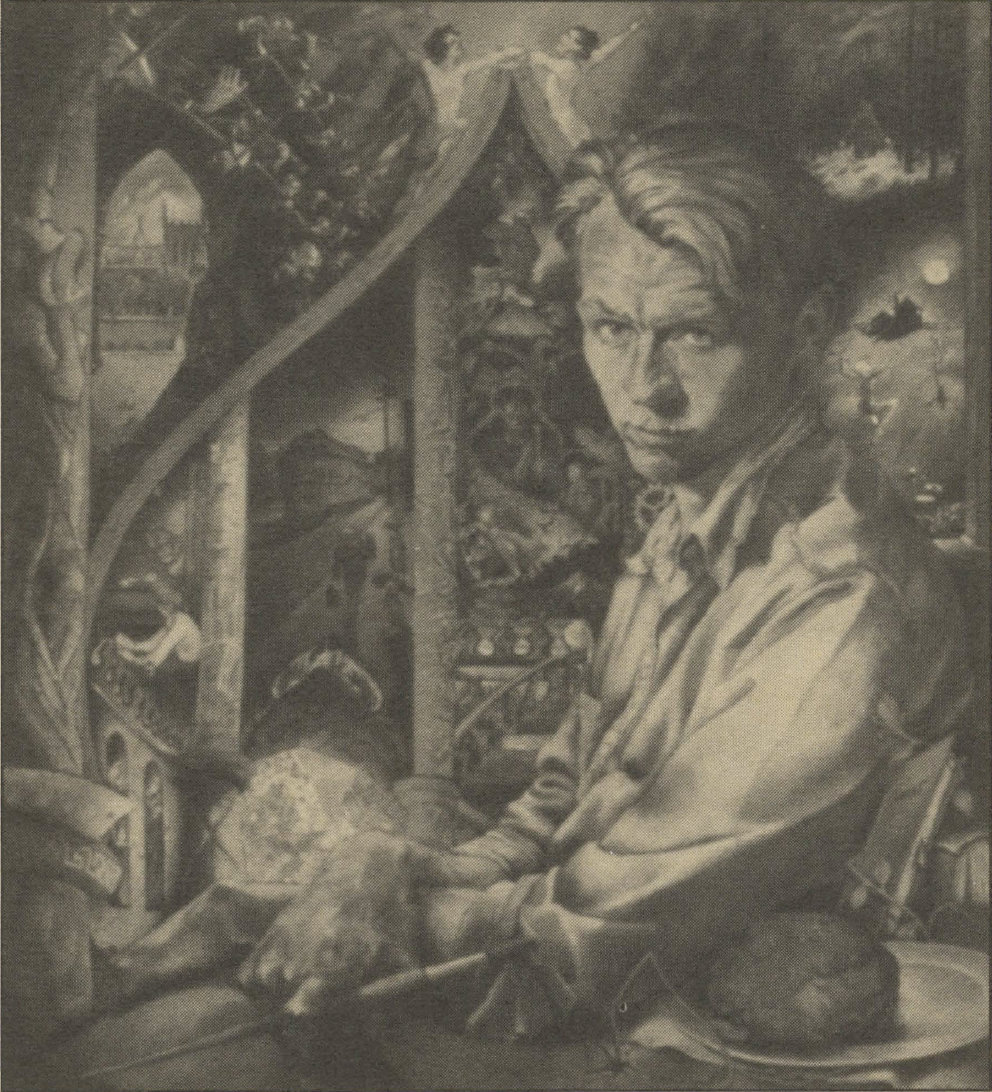

William Kurelek, Self Portrait (1950, 1953), courtesy The Isaacs Gallery.

Morley’s biography fills out that outline with names and dates, quoting freely from Kurelek’s autobiography, Someone with Me, and from interviews with Kurelek’s associates. Nevertheless, though the book is plump with detail, none of it seems to help much in understanding Kurelek. Kurelek was a man of contradictions, and Morley certainly makes us aware of that, but something more than enumerating his inconsistencies seems called for.

Morley’s Kurelek sets out to examine the psychology of an artist, but it does so without the slightest concern for a consistent psychoanalytic position. Morley accepts coffee-table Freudianism as if that provided an empirically true set of rules about the nature of the human psyche, and in so doing, she does Kurelek a disservice and leaves us none the wiser about a difficult man.

At the same time, Morley sets out to assess Kurelek’s art and seems to feel this can be done intuitively. She formulates no aesthetic position from which Kurelek’s success as an artist (apart from his success as a seller of his art) can be assessed. Either Kurelek is a brilliant artist who captured the spirit of the prairies, or he is a talented hack who capitalized on a few cliches. The distinction matters.

Morley’s book follows the four thematic areas that Ramsay Cook identified in an earlier essay. Kurelek is pioneer painter, prairie painter, ethnic painter and religious painter. None of these categories turn out to be much help, since they turn the discussion to subject, and away from technique and accomplishment. The book is well illustrated with snapshots of Kurelek and his friends and family. It is less well illustrated with Kurelek’s work, though Morley describes paintings in great detail as a substitute for assessing them.

Writing a biography is a huge responsibility. Anyone who takes on the task of attempting a psychological and evaluative study of an artist should have some clear notions of psychology and aesthetics. Morley doesn’t. In spite of the enormous number of people and institutions thanked in the book and the evidence of research, the work still seems slapdash. In the end we are left not with a set of unanswered questions but with a collection of unquestioned answers. ♦

David Arnason is a Winnipeg poet, short-story writer and editor. He recently returned from an extended stay in Europe.